Editorial: Palm Springs bulldozed a Black neighborhood. Compensate survivors

Pearl Devers remembers coming home from school near downtown Palm Springs in the 1960s, to the house her father built, only to find a neighbor’s home gone, replaced by a pile of rubble. As the days and weeks went by, other homes within the square-mile area in which she lived disappeared, and the remains were set on fire.

One day it happened to her own home.

“It was very scary,” Devers, now 72, said. “Our neighborhood was a place of safety and community” — until the city began evicting every resident of the small area known as Section 14, beginning in 1959 and continuing through 1966. Residents included Latinos and Native Americans. A majority, including Devers’ family, were Black.

Their modest houses were within walking distance of the palatial desert homes of movie stars. That was the whole point. Devers’ mother was a maid for Lucille Ball. Her carpenter father helped build the local hospital and golf courses. Many other residents in the working-class community served as cooks, chauffeurs and gardeners for wealthier white neighbors as the city became a playground for the Hollywood elite.

In 1921 a white mob rampaged through the Black Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood, killing scores and destroying 25 square blocks of businesses and homes. The past is not really past.

But the land the little community was living on, which belongs to the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, became much more valuable when laws changed to enable long-term leases. The city saw a chance to replace an unpretentious community of color, who had to renew their leases every few years, with glitzy hotels and shops that needed 99-year leases to pencil out.

So it began the process of evicting, demolishing and burning. Survivors say that confiscations often came with little notice, and that keepsakes and valuables were lost along with the homes.

A 1968 report prepared by California Assistant Atty. Gen. Loren Miller Jr. called the destruction, most of which took place two to three years earlier, a “city-engineered holocaust.”

Miller contrasted the losses with the notorious 1961 Bel-Air fire, in which 484 homes were destroyed, most of them belonging to wealthy white residents including famous movie personalities, some of whom no doubt had second homes in Palm Springs that were cared for by residents of Section 14. Miller noted that the rich victims of the “natural holocaust” received federal recovery assistance. There was no such aid to the Palm Springs working-class residents.

Condemning the Bruce family’s Manhattan Beach property in the 1920s was an attack on basic the American values of business initiative, investment, free enterprise and economic wealth. Restoring the property to them is a vindication of those values.

The Palm Springs clearance is just a piece of other injustices, large and small, against Black Americans in the century and a half since emancipation. The most notorious case may be the Tulsa, Okla., race massacre of 1921, in which the wealthy area known as Black Wall Street was destroyed. The best known in Southern California, since it received wide publicity last year, may be the confiscation of Black-owned land and businesses at Bruce’s Beach in the city of Manhattan Beach.

These are just a few of the examples of Black communities that followed the rules of the American dream — working hard, investing their savings, building a future for generations to come — only to have their accumulated wealth destroyed or stolen.

Recovery was next to impossible because of the layers of discrimination against people of color. For example, Devers’ family in theory could have moved their house to another parcel. But that would require money, and in that era banks seldom made loans to Black borrowers. Because there was little access to capital, working-class families fell into poverty. Because of racist attitudes that continue to this day, those same families were blamed for their fate. Loss of property melded with emotional loss and created enduring racial trauma.

Palm Springs, to its credit, last year owned up to the wrongfulness of its 1950s and 1960s actions and issued a formal apology. Past Mayor Christy Holstege, who currently is running ahead in the vote count in her race for the state Assembly, was a vocal supporter of an apology. But so far, there has been no memorial and no compensation to the survivors.

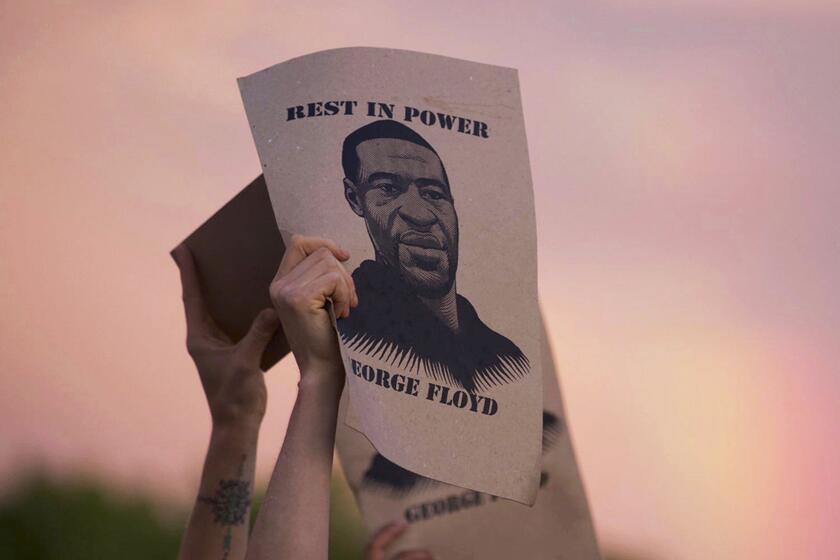

George Floyd’s 2020 death turned a traumatic year into a national self-examination of racism, justice and policing. But what has come of it?

Devers and other survivors have been gathering virtually and in person to discuss their next move, and they’re stepping up their effort to amplify their story.

So far, there has been no formal process to identify those who lost homes and personal property to the fires, which Areva Martin — attorney for the survivors group — noted were set not by arsonists but by the city Fire Department.

It was a scene straight out of Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451,” the novel in which firefighters of the future work not to put out fires but to burn items deemed threatening to those in power.

“The city wants to make amends and we want to help guide them through what that process looks like,” Devers said. Any reckoning should include an attempt to identify the displaced families and their descendants. The historical record should be complete and correct.

And the rest of us should acknowledge what happened in Palm Springs — and recognize that there are similar stories waiting to be told, up and down California, and around the nation.

More to Read

Updates

11:31 a.m. Nov. 17, 2022: An earlier version of this story noted that survivors would be gathering Thursday in Leimert Park. That meeting has since been postponed.

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.