Op-Ed: Why book bans and voter suppression go hand in hand

In the lead-up to the midterm elections, mainstream media attention focused some — though not enough — on voter suppression efforts, but too little attention was paid to the book bans that are metastasizing in states across the country. The same factions that have tried to gerrymander their way into power are trying to gerrymander our education, suppressing the ideas and lessons that hold the keys to what we have long endeavored to become: a fully inclusive multiracial democracy.

The links between these book bans and the efforts to block Black and brown voters from the polls are as connected as the interstate routes that connect the dots on a map of our country.

Of the more than 21 states that have enacted voter suppression measures, nearly all of them have introduced measures to suppress the very ideas that have emerged from the monumental expansions of democracy since the mid-20th century.

PEN America reports that between July 2021 and June 2022, nearly 1,700 book titles have been banned across the country — with books written by or about people of color and queer people disproportionately singled out. The magnitude of this assault on our children’s right to learn cannot be overstated. But most voters who tune into politics once every two or four years for an election are not likely to be aware that the classics of their childhood, written by Black authors like Toni Morrison or Zora Neale Hurston, or works by a new generation of brilliant writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jason Reynolds, are being removed from the shelves of school libraries.

At first glance, the act of suppressing “freedom knowledge” might not feel as urgent as the reimposition of racist voter restrictions. When bad actors try to change the rules at the ballot box to extend their power, we can see how democracy suffers. But when they go after the stories and experiences of traditionally marginalized citizens, when they try to separate “Black history” from “American history” — ignoring how violence and repression in our past have weakened our entire democracy — it can be harder to see how these actions leave us at risk of losing the democratic experiment.

What a truthful accounting of history would teach us about the current political moment is that suppression of votes and the silencing of voices have always been deeply intertwined. What we know from the overthrow of Reconstruction and from every battle since over who is a legitimate stakeholder in this democracy is that violence, changing the rules and placing some voters under threat and suspicion are the staples of racial tyranny in our country.

This is the uncomfortable truth about the Jan. 6 insurrection: The election lies that drove so many to believe that someone had stolen something from them weren’t colorblind. They were racial. As Cliff Albright of Black Voters Matter pointed out, it was voters in Atlanta, Milwaukee, Detroit and Phoenix who got the insurgents’ blood boiling. Yet these dangerous patterns of racial resentment are exactly what those who seek to ban antiracist education want us to ignore. Of course, if we cannot call out white supremacy, we will never be able to overcome it. When honest discussions and examination of racism are made unspeakable, then a truly inclusive democracy is unattainable.

Telling truths about who we Americans are includes grappling with who we have been. That so many communities and states would ban the truth of this nation’s history reveals something terrifying about the current state of our politics.

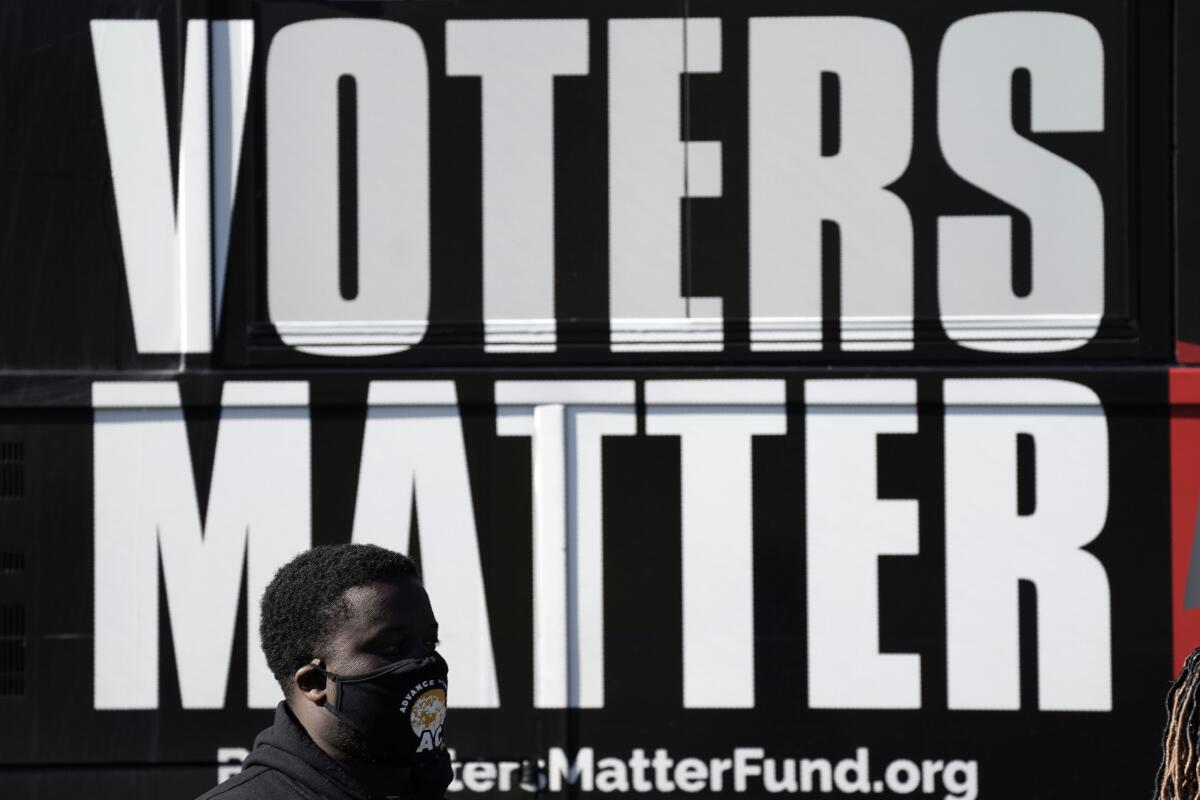

Voting is essential in any democracy. But so is memory. Maybe you, like me, remember the images of Black voters standing in outrageously long lines in the 2020 election. And perhaps that stuck with you as a profound visualization of how right-wing politicians feel about Black voters.

But I want to tell you of a more recent image that stuck with me, one I witnessed when I traveled with the African American Policy Forum to pass out 6,000 banned books in a get-out-the-vote tour with other organizations around the country last month. When our bus pulled into Wilmington, N.C., we stopped at the site of the 1898 Wilmington race riots, which has been recognized by historians as both a coup d’etat and a massacre of leading Black lives in the community. On Nov. 10, 1898, a mob swarmed the offices of the Black-run newspaper the Daily Record, seeking retribution against its editor for editorializing against lynching. Then, under the guise of a “White Declaration of Independence,” white supremacists took over the city’s government, expelling both white and Black elected officials and replacing them with unelected white insurrectionists.

Wilmington would never, ever be the same. Nor would our country.

Yet at the site of the Daily Record, there was no marker of this event, no tribute there to the 60 to 250 people (depending on estimates) who died as a result of the attacks, no cautionary acknowledgment of the horrors that happen when racial aggression is manufactured by demagogues, amplified by media and ultimately erased by those who celebrated the coup as righting the wrongs of a multiracial democracy.

This toxic brew of racial aggression and historical erasure is what we are facing today.

Standing at this historic site, we were only blocks away from the nearest polling place, the Martin Luther King Jr. community center. A few blocks connected this critically important past to a polling place in this democracy. It struck me that this proximity to our past, to our continuing need for racial reckoning, is why opponents of democracy want to stand in the way of our children learning their true history.

This truth, this proximity, this connection is what made the simple act of distributing banned books so profound. When extremist school boards tell our children that they cannot read about the story of Ruby Bridges, they are not just banning books. They are erasing the very real stakes we all have in deepening the fight against antidemocratic factions that have long relied on racist incitement to enhance their agendas.

Suppressing these histories, like vote suppression, are assaults on people, on communities, and on the tattered bonds that hold us together.

We have to connect these dots if we’re to carry on the fight to defend our stake in this democracy.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw is a professor at the Columbia University and UCLA law schools and executive director of the African American Policy Forum.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.