Op-Ed: If America has reopened, why are detained migrants still not allowed visitors?

As COVID numbers have declined in the U.S. we’ve lifted masking, vaccination, social distancing and testing mandates across the country. People are going to concerts and ball games, eating dinner in restaurants and sending their kids to school “normally.” The message is clear: America has reopened.

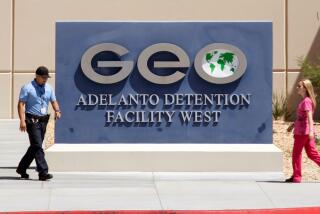

But there is an important set of spaces that remain in strict lockdown: immigrant detention centers.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, part of the Department of Homeland Security, suspended visitation at immigrant detention facilities in March 2020 due to COVID-19. For more than two years, no one other than attorneys — no family members, friends or volunteer advocates — has been allowed to enter these sites or visit those held there.

Biden’s commitment to stop private contracts for federal prisons should expand to include ICE centers.

The only connection migrants in ICE detention centers have to their families and friends is through emails, video and phone calls and physical letters. However, those detained may fear that these forms of communication, as opposed to face-to-face visits, will be closely monitored. In any case, as virtual classes and work meetings have proved for so many people throughout the pandemic, online interactions are not an equal substitute for in-person interaction.

Being held in an immigration detention facility is not a punishment for breaking a law. Migrants are waiting for the adjudication of their immigration cases in civil court. Many are asylum seekers and more than 60% of those held have no prior criminal record.

But while immigration detention is not supposed to be a punitive prison sentence, it is still a form of incarceration. Most of those detained are navigating a confusing bureaucracy. Investigations and lawsuits uncovered patterns of substandard medical care, sexual abuse and solitary confinement in immigrant detention centers during the Obama and Trump administrations. Despite efforts to improve the problems, reports of abuse continue under the Biden presidency. All those held in ICE detention centers live confined in limbo, at best repeating daily routines controlled by the facility’s staff.

Being denied visitors only exacerbates that limbo. ICE recognizes what it calls “the considerable impact” of suspending visitations, and after the lockdowns of the past two years, the ill effects of isolation should be clear to all of us. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes in its guidance on management of the virus in correctional and detention facilities that “restrictions on visitation and programming are known to lead to negative impacts on mental health and well-being.”

Decarceration will cost jobs, but not “good” jobs. Curbing the prison industry will ultimately benefit the economy and interrupt a cycle of trauma.

Visitors, whether family members, friends or volunteers, provide important social and emotional support for migrants in the indeterminate world of detention. Volunteer-driven programs, such as the one run by Freedom for Immigrants, train networks of people who visit with and advocate for people held in these facilities. Organizations like these can also help to hold those who abuse detained migrants accountable by bringing attention to the suffering many in detention facilities have endured.

When ICE first suspended visitation, COVID-19 cases were spreading in nursing homes, prisons and other “congregant settings” — including immigration detention centers. It was clear the virus was dangerous and easily transmissible. But a policy decision that was inevitable in the spring of 2020 isn’t justifiable now. Federal prisons allowed in-person visitation again only seven months after suspending it in those facilities. With vaccines, distancing and masking, even a detention center can be open to visitors and operated safely.

Most of us have been able to get back to some sort of normalcy and to safely see the people who matter most to us. Those detained deserve an end to their isolation too. The Biden administration and ICE need to reopen immigration detention facilities for visits from advocates and loved ones.

Luis A. Romero is an assistant professor of comparative race and ethnic studies at Texas Christian University.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.