Op-Ed: War crimes or genocide? Either way, we can’t let Russian atrocities go unanswered

Civilians shot while riding their bikes. A victim, hands tied behind the back with a white cloth, lying dead in the street.

The images from Bucha, Ukraine, have provoked outrage. President Biden called the Russian atrocities a war crime and called for a tribunal. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky went a step further, naming it “genocide.”

Words matter. They can also be highly political. This is particularly true of the term “genocide.” The term sparks moral outrage and suggests the need for immediate action.

Rescue efforts continued Monday outside Kyiv as Biden and European leaders called for swift action against Russia for civilian deaths.

In international law, what’s key to defining genocide is the perpetrator’s intention. Genocide refers to “the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such,” according to the United Nations. It includes not just killing and “serious bodily or mental harm,” but also trying to destroy the group by creating difficult “conditions of life,” including preventing reproduction or forcibly transferring children from one group of people to another.

War crimes, meanwhile, refer to atrocities committed against combatants and noncombatants while a given party attempts to defeat a military adversary. War crimes encompass everything from killing or abusing prisoners of war to attacking civilian and nonmilitary targets such as hospitals and homes.

As Biden and others have stated, Russia has committed war crimes in Ukraine. This point is underscored by Russia’s indiscriminate bombardment of Ukrainian cities, including a maternity hospital in Mariupol, a city that has been largely destroyed.

Russia has also almost certainly committed crimes against humanity, or widespread attacks on civilian populations. Crimes against humanity can include execution, rape and population transfers — acts Russians appear to have committed against Ukrainian civilians.

Genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing, or the forced removal of a group from an area to make it more homogenous, are often collectively called atrocity crimes.

The international community has recognized that each state has a “responsibility to protect” its populations from atrocity crimes. If a country fails to fulfill this obligation, U.N. member states are supposed to act.

This broad obligation to respond to atrocity crimes is important. Atrocity crimes may take place, as they are in Ukraine, in tandem.

As Biden’s reluctance to call the atrocities in Ukraine genocide illustrates, there are a number of difficulties in making a determination of genocide. Beyond political hesitations, it is hard to determine the intent behind the acts, a requirement for declaring it genocide. Gathering evidence to demonstrate a systematic genocide can also take time — even if it is clear that a place like Ukraine is at high risk for genocide. Recent statements by Russian state media calling for the “denazification” of the majority of Ukrainians, which echo an earlier statement made by Russian President Vladimir Putin, further heighten the concern.

For now, war crimes and crimes against humanity are easier to identify. Like genocide, they demand a response even if a political determination of atrocity crimes does not flip a switch and compel intervention.

So is there more that can be done in Ukraine given that Russia has committed atrocity crimes, perhaps including genocide, in Bucha, Mariupol and other parts of Ukraine?

Absolutely.

First, the sanctions on Russia can be further increased. The U.S. and its allies already appear to be preparing to do this in the aftermath of the Bucha revelations. But key actors can do more, including further cutting off Russia’s oil revenue. Germany, in particular, has been hesitant to do so, but its position could shift given the country’s own history of genocide.

Second, key stakeholders can intensify their diplomatic efforts. On the one hand, more robust diplomacy is needed to help Russia and Ukraine reach a cease-fire agreement in the short term and peace in the long term. On the other hand, diplomats need to encourage and pressure nations such as India, Israel and some Arab League countries to join the sanctions against and diplomatic isolation of Russia.

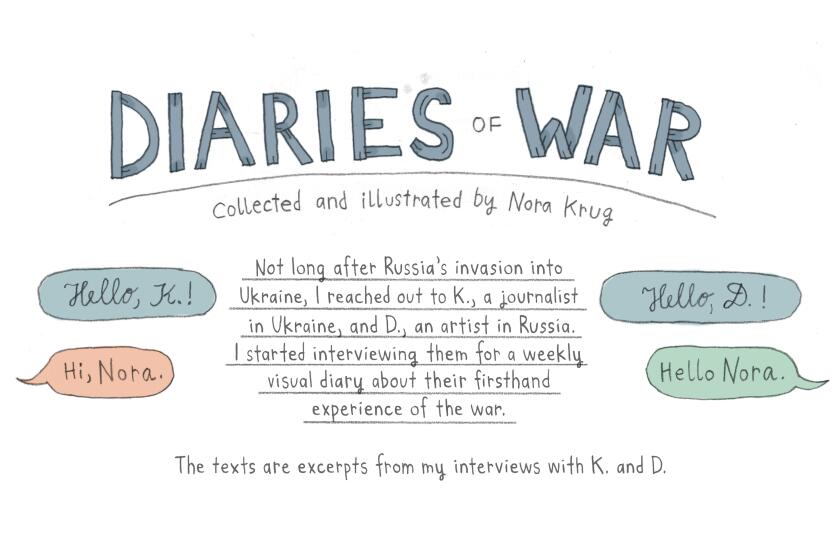

D. finds that it’s too dangerous to talk about the war to anyone who isn’t a friend. K. interviews Ukrainians in Mariupol, a city nearly destroyed by shelling.

Third, North Atlantic Treaty Organization countries can increase their military aid to Ukraine. Given the threat of nuclear war, direct military intervention is a nonstarter. But NATO members could provide more of the weapons Zelensky has sought, including tanks, missile defense systems, drones and armored personnel vehicles.

Finally, down the road, countries can be held to account for atrocity crimes through legal measures, including investigations, commissions of inquiry and criminal accountability.

Ukraine has already launched a case at the International Court of Justice. Human rights organizations are gathering evidence. And, as Biden suggested, an independent tribunal or domestic court could prosecute Russia for its crimes.

But we must not wait to see whether those efforts ultimately deem what’s happening in Ukraine a genocide to decide our actions. The international community has a formal responsibility to protect civilians from precisely the sort of atrocity crimes that Russia is committing in Ukraine. Bucha underscores the importance of acting now.

Alex Hinton is a professor of anthropology and the director of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights at Rutgers University, Newark. @AlexLHinton

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.