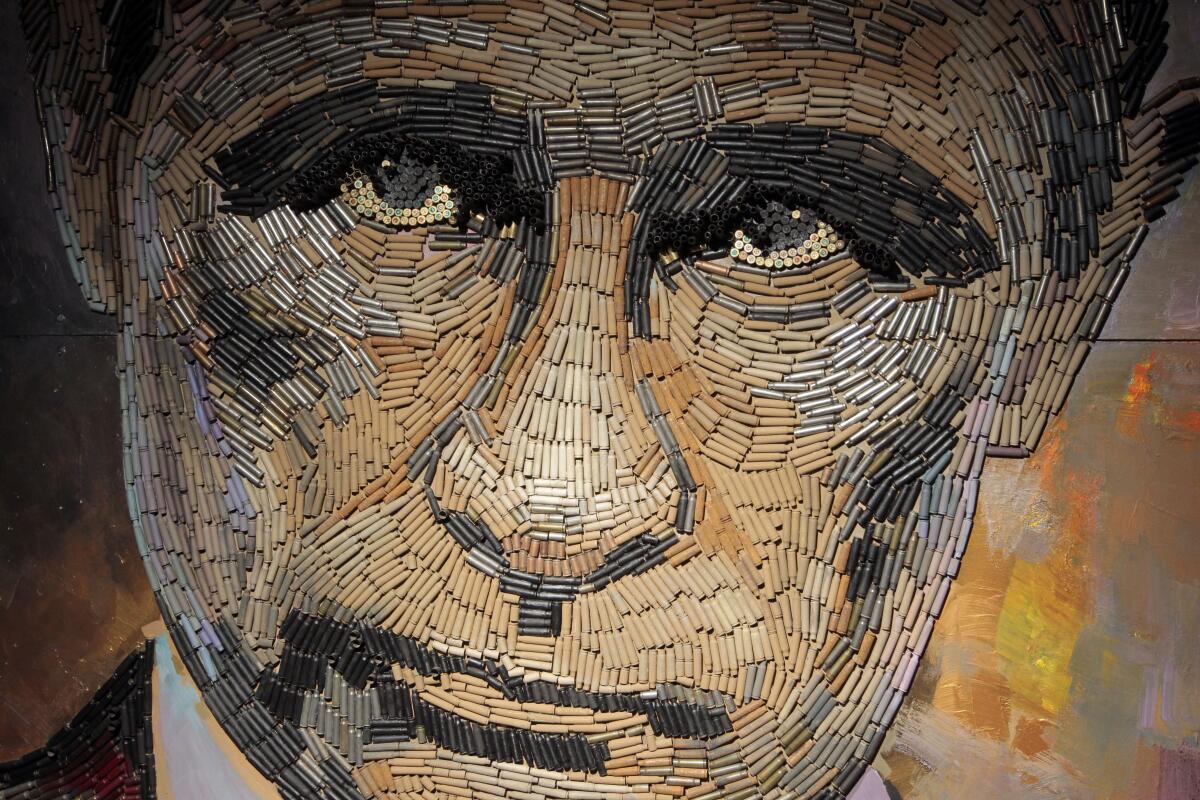

Op-Ed: Why Putin sees Ukraine as an existential threat

After months of buildup, Russian tanks crossed the border this week to invade Ukraine. Without any foreseeable diplomatic path to a peaceful resolution, the West must find ways to deter further aggression by Russia. President Biden has opted for economic sanctions. But will that be enough?

The White House announced on Tuesday that the U.S. and its allies will impose sanctions against Moscow. Biden threatened more sanctions if Russia advances with the invasion. The sanctions target large Russian financial institutions to cut off Western financing to the Russian government. The move comes after France, Britain, Germany and the U.S. all made offers to negotiate with Russian President Vladimir Putin in recent months.

Putin has described his troops in the separatist areas, known as Donbas, as “peacekeepers,” and continues to make ridiculous demands for potential talks. In an address this week, he insisted that Ukraine recognize Russian sovereignty over Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014. Biden promised that the latest sanctions would go “far beyond” what the U.S. and its partners imposed during the Crimea crisis. The administration also said it’s ready to take actions against Russia’s largest banks.

President Biden announces plans for additional sanctions on Russia. But he and other allies question whether they will only further provoke Putin.

Sanctions, however, are an imprecise tool in international politics and they can take a long time to do damage to the targeted country. The U.S. and European sanctions since 2014 have inflicted only moderate pain on the Russian economy as a whole. Russia managed to find new markets and investment in China and the Middle East to replace what it lost under U.S. and European sanctions. In 2021, the Russian economy grew at a reported 4.3%. In addition, thanks to import substitution, Russian agriculture has enjoyed a renaissance over the last decade. The prices of oil and natural gas, which make up close to 40% of Russian export revenue, are soaring on global markets.

Still, in the face of Russian hostility, the U.S. cannot directly intervene militarily without risk of a broader conflict with a modernized, reformed and nuclear-capable Russian military. That leaves sanctions as the main instrument at hand. But if these measures did not work well before, will they be effective this time around?

Part of the answer depends on what we expect sanctions to accomplish. We don’t know how far beyond Crimea and the Donbas region Putin’s troops might have pushed in 2014 had sanctions not been employed. Did they prevent him from going further into Ukraine? It’s entirely possible they did deter Putin from seizing even more territory. Of course, those sanctions have not prevented the current incursion eight years later.

But the sanctions unveiled Tuesday are stronger, and potentially more damaging over time, with more to come. The European Union kicked things off by sanctioning the 381 (out of 450) members of Russia’s State Duma, who endorsed Putin’s recognition of the Luhansk and Donetsk separatist regions as independent. This means that Duma members cannot travel to Europe, nor can their wives or children; nor can they access any assets that they may have in European banks — and some of them have a lot to lose. For others though, this will be little more than an inconvenience.

In addition, the German government stopped the process of certifying the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which was expected to come online in the next year or so to transport billions of cubic meters of Russian natural gas into Germany. (Yet if the Russian military ends up seizing all of Ukraine, or the central part at least, then Russia would gain ownership and control over the network of existing pipelines that run from Russia through Ukraine to Europe that Nord Stream 2 was supposed to render obsolete.) Though the Nord Stream 2 project is incomplete, Germany’s decision is an important signal to Putin that the West is united and resolute in opposing him.

It’s hard to see how all-out war in Ukraine would end well for Putin. There’s no reason to believe the Russian people want to see thousands of Russians die.

Over time, Biden’s new tranche of sanctions should do real damage to the Russian economy. These include full-blocking sanctions on VEB, the Russian foreign trade bank, and the government bank that funds Russia’s military. The banks will be prevented from doing business with American or European banks. Even more effective potentially are the comprehensive sanctions on Russian sovereign debt that will essentially prohibit the Russian government from borrowing from the West and prevent it from trading in Western debt markets too. In the days ahead, Biden has promised further sanctions on other wealthy Russian elites and their businesses presumably to get those around Putin to persuade him to withdraw Russian forces from Ukraine — or at least to not go any further.

The Western allies have promised that sanctions will ratchet up commensurate with Putin’s next moves against Ukraine. This pressure might influence what happens next, especially if it begins to cause real economic pain to more Russian elites. And if average Russians get hit and begin to doubt the wisdom of their president, they could spill out onto the streets with the sort of mass demonstrations that Putin detests. (Russians have shown that they’re capable of significant opposition and protest when pushed, as witnessed most recently when opposition leader Alexei Navalny was detained and imprisoned.)

What Putin fears in Ukraine is not NATO expansion on Russian borders. The last states on Russia’s border to join NATO were the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia in 2004. There is no security threat to Russia from Ukraine.

But there is in Ukraine an existential threat to Putin’s personal and autocratic regime: the example of a resilient, robust, pluralistic democracy next door in a country whose history is intertwined with Russia’s own. Ukrainians have continued to cling to their imperfect but open political system with checks on the executive by an independent legislature and judiciary, vibrant civil society and free press. This system — not NATO — is the real threat to the aging autocrat, and it will take maximum pressure from the West and by Russians themselves to persuade him to back down.

Kathryn Stoner is a political science professor at Stanford University and Mosbacher Director of the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law. Her most recent book is “Russia Resurrected: Its Power and Purpose in a New Global Order.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.