Column: This is the longest, slowest concert ever. It began 21 years ago and is just getting started

In 1987 the avant-garde composer John Cage wrote a piece of keyboard music called “Organ²/ASLSP.” The score is eight pages long. But Cage left an unusual instruction for those who wanted to perform it: “As Slow As Possible.”

What’s “possible,” of course, is open to interpretation. One performer played it at 29 minutes, another at 71 minutes and another at 8 hours. One performance lasted 14 hours and 56 minutes.

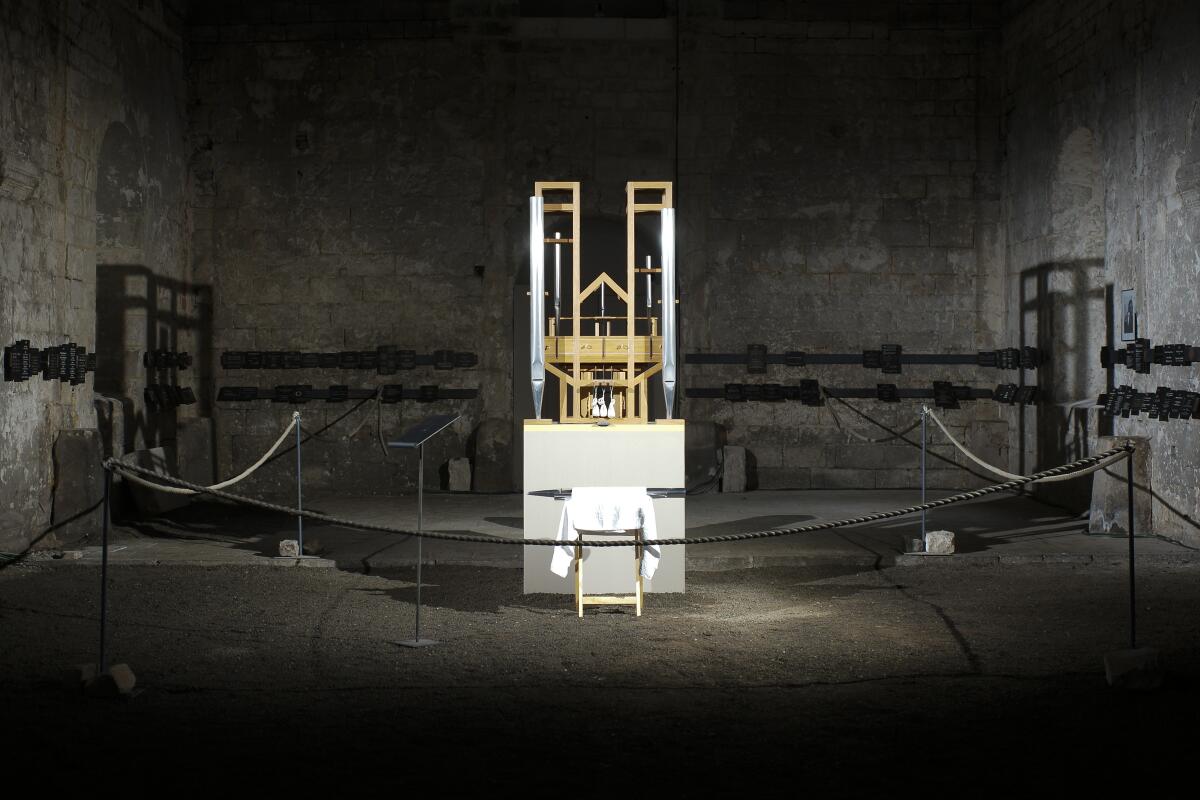

But now — well not now, exactly, but 21 years ago — a group of Cage lovers decided to do them one better. So they built a special organ, put it in a run-down medieval church in the town of Halberstadt, Germany, and announced that they were going to play “Organ ²/ASLSP” really, really slowly — over a period of 639 years. The performance is scheduled to conclude in 2640.

So what are we to make of this? Is it a thought-provoking experiment befitting the creative author of the work — or a ludicrous prank being played on his memory and on the rest of us?

Opinion Columnist

Nicholas Goldberg

Nicholas Goldberg served 11 years as editor of the editorial page and is a former editor of the Op-Ed page and Sunday Opinion section.

Here’s what you should know about the performance so far. It began in September 2001, but nothing happened. That’s because the score opens with a rest, a musical notation that indicates the absence of sound. It was 17 months later that the first chord was heard, and the concert has been going continuously, 24 hours a day, ever since. I read about it in a Wall Street Journal article in 2003 and found it intriguing and amusing, but I then forgot about it for 18 years. Luckily I didn’t miss much. Only 12 chord or note changes have occurred since then.

The performance is just getting underway.

The next change — and this is the breaking news peg that makes this column so timely — will occur on Saturday, Feb. 5. The note in question is a G-sharp, which will cease to sound on that day. It will have been played steadily for 518 days, which is possible because an organ note (unlike a piano note) can sound indefinitely as long as the key is continually pressed, which is what’s been going on in this case through the use of sandbags.

Some notes or chords in the performance sound for several months, others for a year or substantially more. The most recent change, in September 2020, was the first in almost seven years.

I’m not an avant-garde type of guy ordinarily. I generally prefer my books to have plots, my art recognizable or at least evocative, and my music more melodic than cerebral.

As the politics of law and order are poised to determine the future of America, John Cage’s 1950 String Quartet in Four Parts stands as music of the moment.

But I try not to be too narrow-minded and fusty. John Cage is one of the most radically innovative musical figures of the 20th century. Born in Los Angeles (his mother wrote a regular column on “Women’s Clubs” for The Times in the 1930s and his father was, unsurprisingly, an inventor), his influence is global and enduring.

I wanted to know more about the Halberstadt project, so I called Mark Swed, The Times’ classical music critic, who knew Cage before his death in 1992 and has written about him extensively. Swed is a huge Cage enthusiast, so I was intrigued to find that he is strongly — perhaps vehemently is more accurate — irked by the 639-year event.

“What they’re doing goes against every single thing John Cage stood for,” he told me. “This is a marketing gimmick. Everything about it is fraudulent. They’re using it as a tourist attraction. It’s not about the music at all.”

Swed says Cage wrote music to be performed. And this is not a real performance. Not only can no performer play the piece — sandbags are the current organist — but the piece can’t be heard by an audience from beginning to end, for obvious reasons. What’s more, Swed says, Cage was all about freeing yourself from ego — but this is all about the ego of the town of Halberstadt, about attracting attention and reeling in tourists.

On the other hand, of course, Cage was also about breaking rules and challenging preconceptions. He used vegetables, toys and radios in his work. A deck of cards. A blender. A toaster.

Ambient sound, noise, silence, chance, time and duration — these were among his themes.

One of his best-known works is “4’33,” a 1952 composition in which the musicians appear onstage and play nothing whatsoever for 4 minutes and 33 seconds, and then step down. The piece is divided into three movements.

So it is really not surprising that there are people who think a 639-year concert would’ve been right down Cage’s alley.

Are we really going to let the unappealing business term “high net worth individuals” replace “rich”? I hope not.

I, of course, will defer to Swed when he says that Cage would have disliked this idea. And when he calls it a gimmick. Of course it is.

But I can’t help it — this performance makes me smile. It’s a stunt, but it’s also a challenge to our drab human tendency to think only in terms of the ticking away of our own lives, the humdrum passing of our days, the hours and minutes of our own short existences.

That “Organ²/ASLSP” may still be playing in Halberstadt hundreds of years after I’m dead — assuming the organ holds out and the funding lasts — is a reminder that sometimes we need to think in terms of generations and centuries and millenniums.

And it’s a reminder that sometimes there’s a value to moving slowly, even very slowly, through our busy, overstimulated and hyper-accelerated world.

How humans will experience the next six centuries depends very much on how we treat the planet in the years just ahead. But there’s something refreshingly optimistic (though very possibly delusional) about believing that 600 years from now people might still gather in a 12th century church in eastern Germany to hear a single strange piece of music by a 20th century composer, played as slowly as possible.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.