Op-Ed: Could this be the year ‘sportwashing’ backfires?

Sport and politics — and the sport of mixing them — are in for quite a year. The Winter Olympic Games in Beijing in February and the men’s soccer World Cup in Qatar in December will bookend 2022, with two antidemocratic host nations seeking to burnish their reputations and exploit the soft power of sport.

There is nothing new about political regimes associating themselves with the games we love to play and watch to improve their branding, in much the same way that car and beer companies do. Americans and Soviets fixated on the Olympics for decades as a proxy battlefield for the clash of our competing Cold War political systems and ideologies.

As a soccer-obsessed kid in Mexico, the first World Cup I watched every minute of on TV was held in Argentina in 1978. It was only much later that I realized the extent to which I had been defrauded: The military junta that presented itself as the paradise of my beloved sport was in fact home to a brutal “dirty war” against its ideological opponents.

And it isn’t only unsavory governments that wield sport-derived soft power. The United States may be its biggest beneficiary, thanks to the overseas popularity of the NBA, NFL and MLB, and the growing role U.S. interests are playing in the world of soccer. Perhaps one reason anti-Americanism has lost much of its political resonance in Mexico is because so many Mexicans have grown up rooting for the Pittsburgh Steelers, Dallas Cowboys or the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Beijing seemed like the right Olympic choice to most people at the time the country was awarded the 2022 Games, but claims of genocide and the strange case of Peng Shuai have led to diplomatic boycotts against China.

The appropriation of sport by powerful states reaches beyond global events into domestic leagues and competitions. Hosting a World Cup wasn’t enough for Qatar — it also acquired the French soccer club Paris St. Germain. Abu Dhabi’s ruling family, meanwhile, owns Manchester City, and Dubai-based Emirates airline sponsors soccer giants Real Madrid and Arsenal among others, as well as Grand Slam tennis tournaments and the America’s Cup.

Envious of their Persian Gulf neighbors’ success at projecting a cosmopolitan and humane image through sport, Saudi Arabia is geo-sport’s rising superpower. The kingdom’s sovereign wealth fund recently acquired Newcastle United in the English Premier League. Last month, the Saudis hosted their first Formula One race, and this month they are bringing the Spanish soccer league’s annual Super Cup to Saudi Arabia.

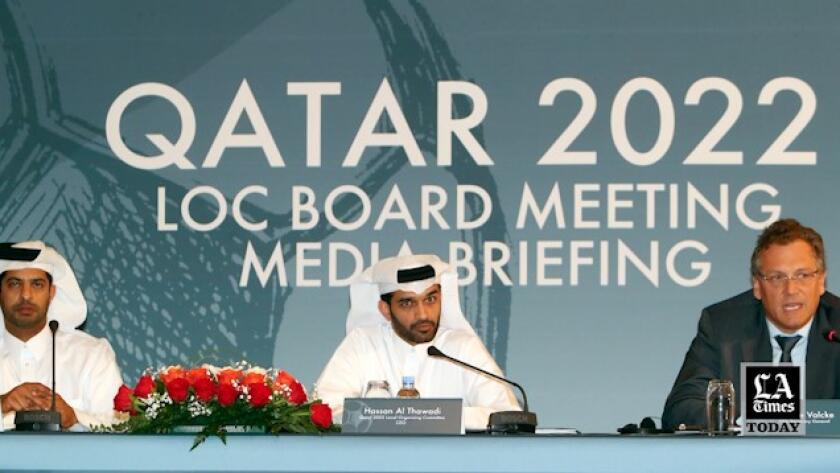

Human rights activists and other critics have coined a term for these moves by deep-pocketed regimes to launder their reputations by sponsoring these contests with global appeal: “sportwashing.” For the laundromats involved, the practice is without doubt good for business, bringing in once unimaginable windfalls. Formula One’s 10-year deal with Saudi Arabia is reportedly worth $650 million. FIFA was roundly denounced when it awarded this year’s World Cup to Qatar back in 2010, but the petrostate is reportedly spending hundreds of billions of dollars on the tournament and it has become a generous all-purpose benefactor of the sport’s governing body.

Although there’s no doubting sportwashing’s continuing business rationale, there are growing questions as to whether it can persist in the face of mounting social consciousness about off-field responsibilities and values, and the rising activism of consumers and athletes.

Tennis recently reminded us that there can be limits to how far we should go to sell off sports to any bidder, at any price. The Women’s Tennis Assn., which had profited enormously by scheduling many of the circuit’s high-profile tournaments in China, courageously decided to suspend its activities in the People’s Republic, after the Beijing government failed to investigate Chinese player Peng Shuai’s accusations of abuse against a former vice premier. The WTA’s stand against China’s apparent cover-up represented a rare triumph for something other than commercial interests.

The new year may well show if the WTA’s resistance is a harbinger of things to come or an exception to the rule.

The Beijing Winter Olympics, scheduled to begin Feb. 4, already face a diplomatic boycott from the United States and several other Western nations. Participating athletes and international brands sponsoring the Games are coming under pressure to weigh in on the issues behind the boycott, including China’s treatment of the nation’s Muslim minority in Xinjiang and its clampdown on civil liberties in Hong Kong. The Games’ hosts, meanwhile, are determined to restrict access to foreign media, and to have the International Olympic Committee strictly enforce rules against athletes speaking out on political issues.

Even if Big Sport doesn’t shy away from catering to unsavory regimes, the market itself might serve as a corrective. The Saudi Arabias of the world want to buy into sport to rehabilitate their image, but the more attuned the rest of us are to the cynical nature of these transactions and the underlying horrors they seek to obscure, the more likely these propaganda attempts will backfire.

Perhaps as the Olympic flame goes out next month and the final whistle is blown at the World Cup in December, sportwashing will have proved as dangerous for China and Qatar as it is for the games we love.

Andrés Martinez is a professor of practice at the Cronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University and a research scholar at ASU’s Global Sport Institute.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.