Op-Ed: My brother was disappeared by mental illness. Here’s how I found him again

When I started writing about my brother’s life, I knew a great deal about grief. I longed for an equal dose of hope. But I didn’t yet know where hope lived in Mike’s story.

I do now.

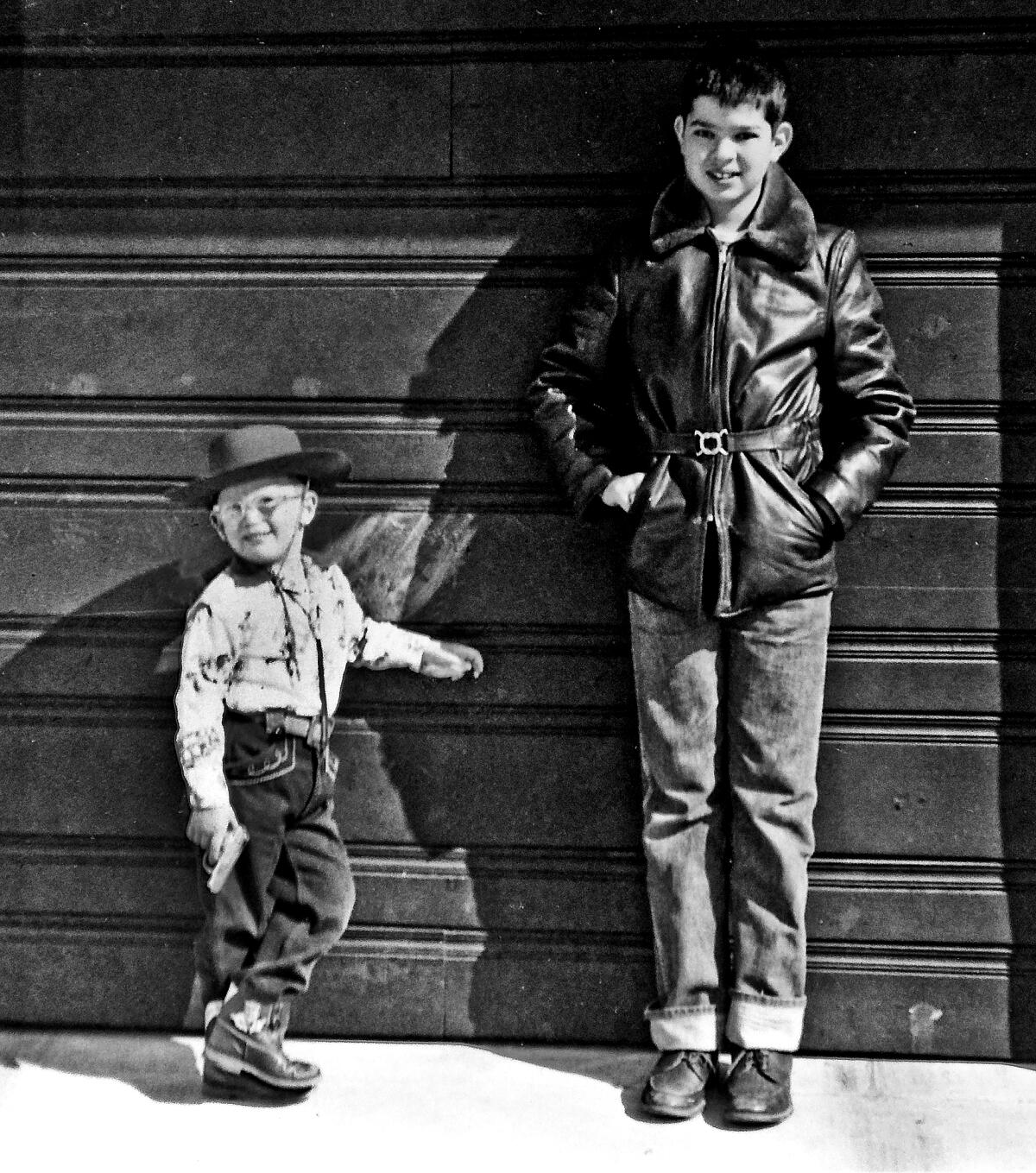

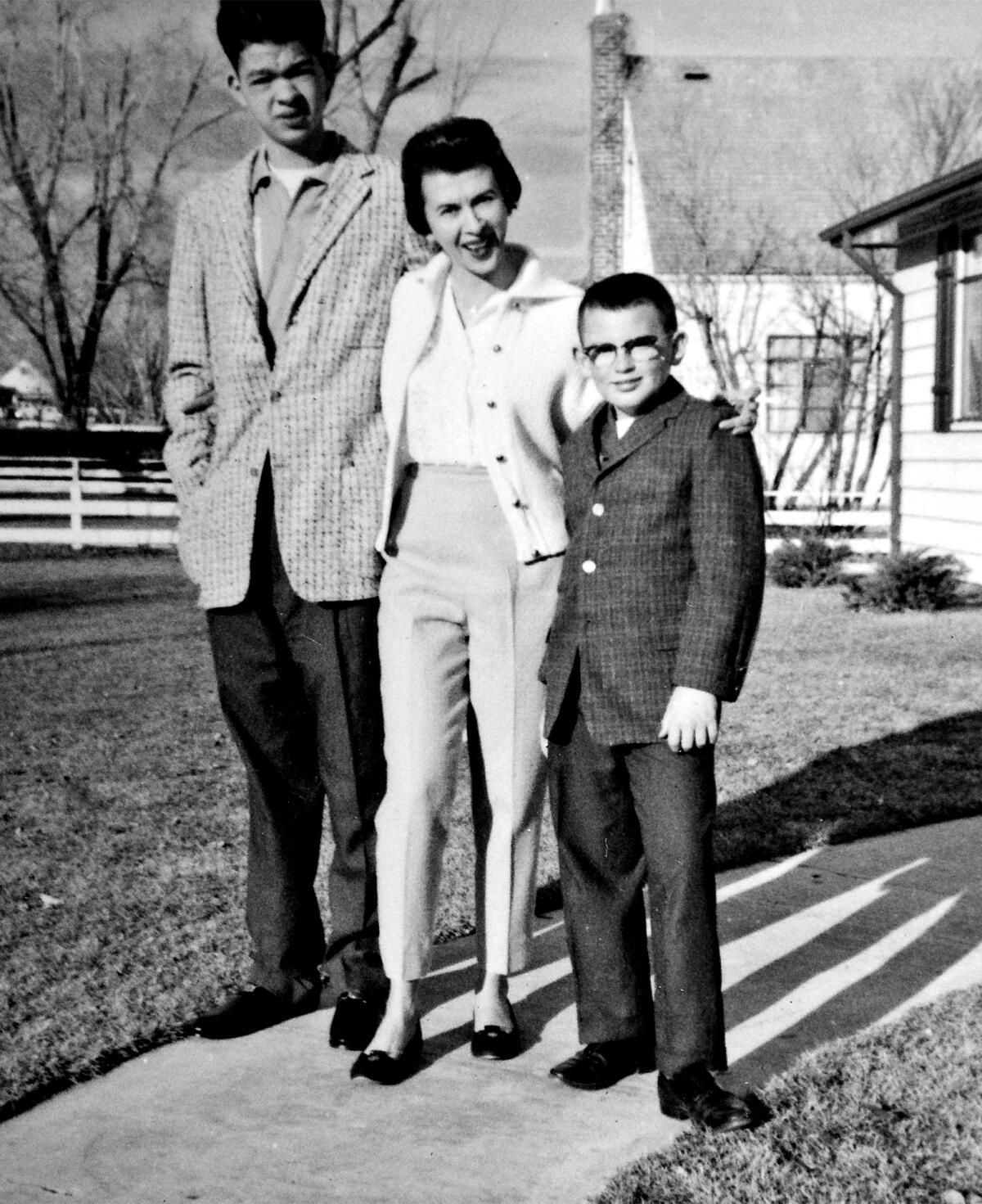

Mike, our mother’s son from a brief first marriage, was eight years older than me. He was a sweet kid, slow to learn and diagnosed as “mildly retarded.” That was the label we used in the 1950s. But when Mike turned 14, rage overwhelmed him and shattered our family. Our parents, desperate for help, asked the state psychiatric hospital for an evaluation. Mike’s new diagnosis: paranoid schizophrenia, capable of violence.

Mike was committed by court order to the Colorado State Hospital, formerly known as the Colorado State Insane Asylum. He never lived at home again.

Why is it so hard to find help for those who are mid-fall? Why do we wait until they hit rock bottom?

My brother’s life mirrors the deplorable history of America’s treatment of mental illness. Beginning in 1957, he spent nine years in overcrowded Colorado mental institutions.

When he was mainstreamed back to Denver in 1966, along with thousands of other troubled people as the mental hospitals emptied their wards, Mike’s visits home triggered emotional chaos. He couldn’t effortlessly rejoin our family after so many years away. Angry and resentful, he cut off all contact.

Ten years later, in 1976, Mike died alone in his boarding home, undiscovered for three days. His autopsy “failed to reveal an anatomical cause of death,” though his brain showed scarring related to a “seizure disorder.” The Denver media used his solitary death to expose “ratholes” that warehoused people with mental illness. Our mother found out about the loss of her 33-year-old son from the front page of the Denver Post.

In subsequent years, she didn’t want to talk about Mike or revisit his life. I deferred to her wishes, to her fragility. I would answer questions about siblings as simply as possible, “I had an older brother — a half-brother — who left home when I was 6. He died years ago.”

Only after both my parents were gone did I risk grappling with the contents of the envelope they had saved — a sheaf of decades-old court and medical records, yellowing newsprint, and letters from Mike. The envelope felt incendiary. But, finally, I spilled the contents of “the Mike file” onto my desk, each page a clue to my brother’s life.

I resolved to resurrect my brother, to re-create his life, to know him for the first time. I tracked down every lead, interviewed every surviving character. But I had no idea that all these notes and words and drafts would eventually bring me closer than I’ve ever been to knowing myself.

Now I no longer think of myself as mostly an only child. Mike was there, all along, the dominant force shaping our family, shaping me. When I saw how disruptive Mike was, I surely chose to be the opposite. Mike was erratic; I was compliant. Mike was hard; I was flexible. I’m shocked that self-realization took so long.

So, where is the hope?

California’s landmark laws to protect the civil rights of psychiatric patients are being improperly scapegoated as the cause of rampant homelessness.

For me, it arrived when I could say, “I see you, Mike.” I moved from silence and denial to acknowledgment. As I opened doors, Mike grew more and more real, more and more a person to me, a singular human worthy of more than clinical summation.

When we refuse to look away as our fathers and mothers and sisters and brothers and children struggle with mental health conditions, we create hope. We choose empathy over fear, compassion over detachment.

As I’ve told Mike’s story in readings and interviews, often paired in conversation with a psychologist or psychiatrist, the clinicians continue to downgrade his diagnosis. It’s likely he didn’t suffer from schizophrenia at all — a catchall diagnosis overused in the 1950s. He might have experienced bipolar disorder or been on the autism spectrum. His paranoia and dementia may have been more cyclic or transitory than chronic, more treatable than inescapable. Mike may have simply been living with depression and learning disabilities.

As Mike becomes less frightening, he grows more flesh-and-blood than memory. In the last photographs I have of him, Mike looks resigned, blank, a more-than-6-foot-tall totem pole anchored to the sidewalk. Now, my storm cloud of a brother begins to soften, to move, to be a real presence.

I keep returning to the letters Mike wrote to our mother when he was freed from the hospital. He sounds achingly self-aware as he cycles between anguish and apology. He writes to our mother, “Leave me alone forever. You didn’t realize a good son when you had me. I am a person with great determination, power, desire, initiative, and confidence in myself. I am getting by in this big deep revolving world.”

“I hope that someday you will realize what I would have been if you wouldn’t have messed me up.”

That “someday” has come, Mike. I’m realizing what you might have been if you had been born 50 years later — and what I might have been if we had been raised together. Your disappearance from our family was a palpable loss, depriving us of a relationship that would have made our lives richer.

Today’s families have set aside some of the stigma and shame tied to mental illness, but less than half of adults with mental health issues receive help. We are a long way from universal access to treatment.

First, we must meet our fears. We must acknowledge the full humanity as well as the challenges of our loved ones. That’s where hope lies, for all of us — when we can say, simply, honestly, “I see you.”

Stephen Trimble, a writer based in Utah, is the author, most recently, of the memoir “The Mike File: A Story of Grief and Hope.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.