Op-Ed: IVF mixups should not discourage expanding reproductive care

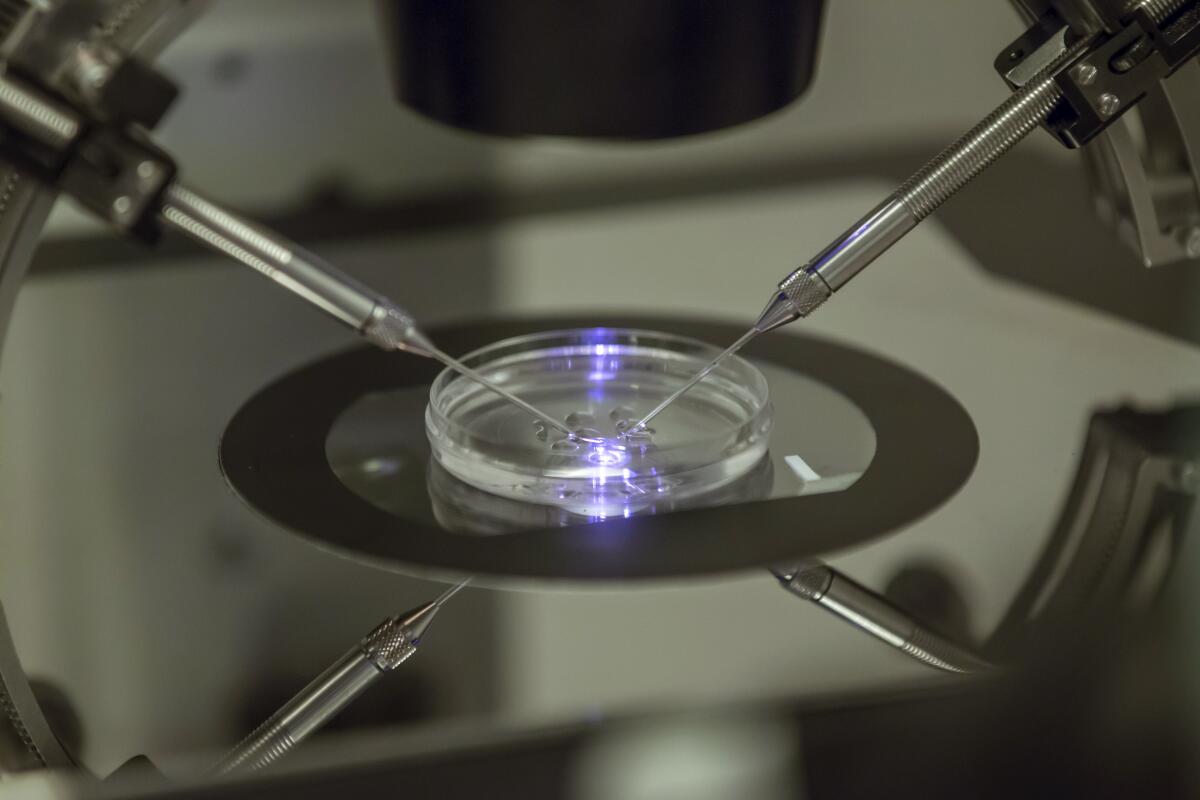

The story is a harrowing one: A family brings home their newborn but immediately doubts the child is genetically theirs. DNA testing reveals the truth: A fertility center in the Los Angeles area had switched embryos between two families and transferred the wrong embryo to each couple during in vitro fertilization. Their children were born a week apart.

After learning of the mistake, the families decided to swap the children, so the parents ended up with their genetic daughters, though they have since kept in touch. In November one of the couples filed a lawsuit against the clinic involved.

A Los Angeles husband and wife have sued a fertility clinic and its medical director after lab tests confirmed they and another couple had given birth to each other’s babies after their embryos were mixed up.

The pain and confusion for these parents is difficult to comprehend and unique to IVF. While stories of children “switched” at birth have happened since the advent of the hospital nursery, this error also resulted in mothers carrying and giving birth to children who were not genetically their own.

But responding to a story like this with fear of IVF or increased regulation would be misplaced. The more pressing issue is a lack of access to reproductive technology for many people who could benefit.

IVF errors are rare. A study published last year found that between 2009 and 2019, out of approximately 2.5 million IVF procedures in the U.S., 133 errors happened that resulted in lawsuits — 87 of which involved two alleged freezer tank failures in 2018 and 2019. A 2018 study of non-conformance with standards from the International Organization for Standardization found that 99.96% of procedures during 36,654 IVF treatment cycles in one clinic network had no violations. In short, the procedure is extremely reliable.

This is not to downplay the distress caused by medical error, which can be devastating. But even if the true error rate in IVF is higher than these studies suggest, it’s likely lower than error rates in medicine overall. Recent studies show 21% of patients report having experienced a medical error.

The Glendale couple thought that their in vitro fertilization treatment had failed.

The unique nature of IVF and fertility care may demand a higher standard for avoiding errors. Those facing infertility often do so with little support given societal stigma, making this a particularly sensitive area of healthcare. Unfortunately, as is the case across medicine, eliminating all error is unlikely.

Some have called IVF a “Wild West” and endorsed federal or state oversight of embryo storage. U.S. regulations are less rigorous than those in countries with socialized medicine and broad access to assisted reproduction, such as the United Kingdom. But IVF is already one of the most highly regulated areas in American medicine, more stringent than, for example, the federal system that regulates medical devices such as vaginal mesh used in pelvic reconstruction and a surgical tool used to remove fibroids and the uterus.

Rather than more regulation, a better path forward for IVF would be to improve processes to achieve informed consent for patients and recognize that rare errors will happen — while expanding access.

Many people who desire IVF cannot access it. An expert panel estimated in 2009 that just 24% of the need for assisted reproductive technology in the U.S. was being met. Worldwide this number is lower.

One reason for lack of access is the cost of providing such technologically complex care. Costs vary widely, but the average IVF cycle including medication is estimated to come to about $25,000. Expenses may go up with additional regulation and technology to reduce errors.

The team behind ‘Master of None: Moments in Love’ explains how they made their illuminating close-up of a frequently misunderstood topic.

As costs rise, access is lessened. Our ideal as a society should be to ensure access to all, not just to typically wealthy and white patients.

IVF by its nature will always remain medically and emotionally complex. Helping patients and their families understand the potential pitfalls and human aspects of this care — including the potential for error — before proceeding is difficult but necessary. Medical educators are refocusing our mission to ensure we help students and practitioners develop communication and other skills to guide patients through that decision making.

Most IVF clinics already rely heavily on colleagues in social work and psychology for support in counseling and achieving informed consent. Collaboration with these colleagues to develop standardized counseling tools, including apps, may further help families understand IVF.

Medical error can be tragic for patients and their families. But so can lack of access to deeply desired, life-changing reproductive care. While reducing errors as much as possible, the field should focus on achieving fair access to IVF.

Louise P. King is an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive biology and the director of reproductive bioethics at Harvard Medical School.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.