Op-Ed: California has to get ethnic studies right to support Black LGBTQ youth

In October, California became the first state in the U.S. to require ethnic studies for high school graduation starting in 2030. Signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom, the measure was the subject of a more than five-year battle over curriculum content, inclusion and conservative backlash against teaching about racism in K-12 schools.

Bucking the reactionary furor over social justice education, all California students will finally have the opportunity to learn American history beyond the standard narratives of heroic straight white males (and a handful of exceptional people of color). Per the state guidelines, core ethnic studies themes focus on identity, history, systems of power, social movements and equity. But the long-term effects on student learning will ultimately hinge on execution — particularly for marginalized Black LGBTQ youth.

Past education mandates illustrate this problem. Despite the passage of the California Fair Education Act in 2011 mandating the inclusion of LGBTQ contributions to American history in K-12 education — also the first of its kind in the nation — LGBTQ-inclusive social history is still minimal in many California schools. Only 31% of California students reported being taught this material in 2019.

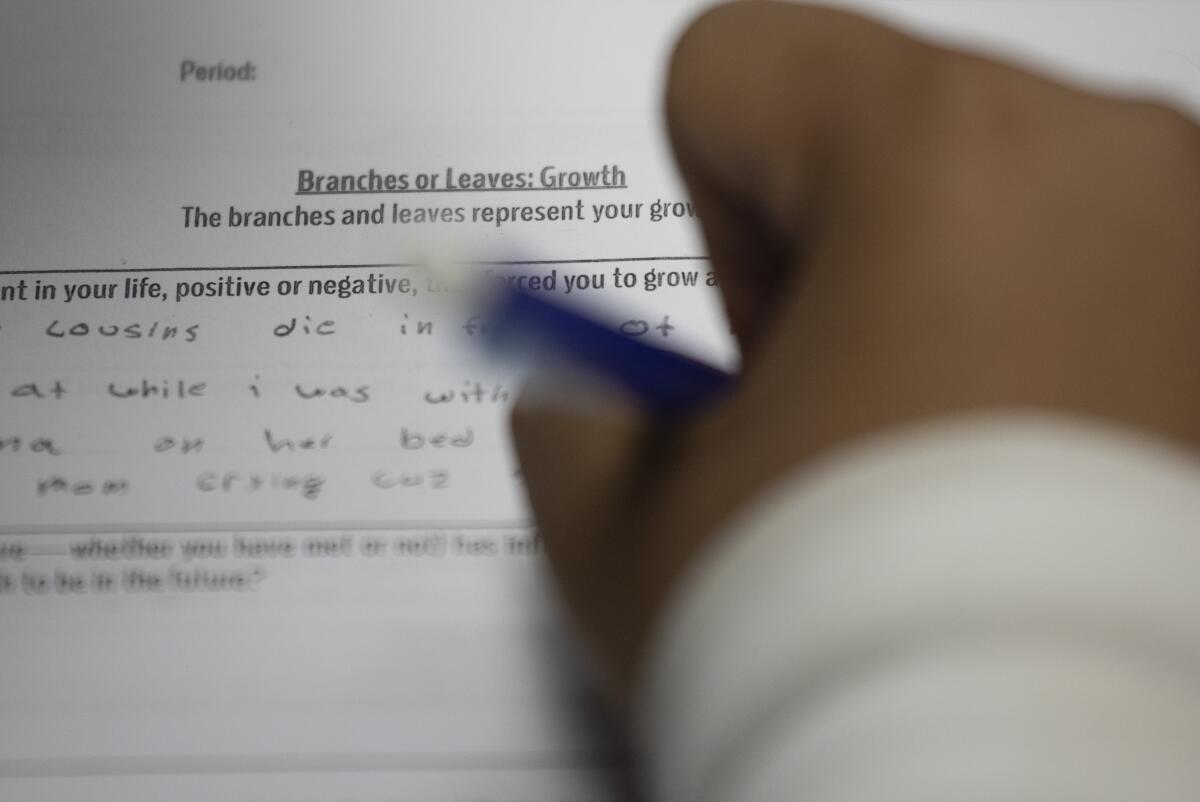

Ethnic studies is now required for future graduating California high school students. A look inside what students talk about in ethnic studies classes.

The lack of representation is especially acute for Black queer youth, who are nearly invisible in the curriculum and often thrust into environments where there are no openly identified Black queer teachers or administrators. Middle and high school students raised these issues during a recent youth virtual event organized by the L.A.-based Black LGBTQI+ Parent and Caregiver group.

Thus, simply requiring ethnic studies courses in schools will not redress institutional racism in classrooms or school communities, much as an LGBTQ education mandate didn’t erase heterosexism or transphobia. For ethnic studies to succeed, it must be part of a broader approach to teaching, learning and social-emotional support for students, taking into account the overlap of racial, gender and sexual identities.

Recently, for example, a Black student told me that their parent threatened to kick them out of the house because they identified as queer. Their experiences were virtually identical to those of another student who told me years earlier that she faced religious hostility and the threat of eviction from her mother when she came out. She was told that being bisexual was against God, Blackness and respectable womanhood. Both youth were victimized at the intersections of misogynoir (a term for anti-Black misogyny) and homophobia. These factors contribute to high rates of homelessness and incarceration among Black queer youth. According to a 2019 Human Rights Campaign report, only 26% of Black youth reported family involvement in LGBTQ issues or the LGBTQ community.

For Black queer youth, bigotry at home is compounded by in-school bullying and harassment and high rates of school discipline. A 2020 report by the National Black Justice Coalition and GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network) concluded: “The majority of Black LGBTQ students experienced harassment in school…because of their sexual orientation, gender expression, or race/ethnicity.”

In the U.S. and Latin America, the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the mental health of LGBTQ young people. Experts give tips on navigating the crisis.

Their survey of self-identifying LGBTQ youth found that this victimization was particularly severe for trans, gender-nonconforming and non-binary Black students as well as for multiracial Black LGBTQ students. These groups appeared to encounter higher levels of social exclusion at school. Moreover, the report noted, “those who experienced both homophobic and racist victimization experienced the poorest academic outcomes and psychological well-being.”

Ethnic studies can make a connection between Black queer legacies of resistance — spotlighting icons such as James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Bayard Rustin and Marsha P. Johnson — and the lived experience of Black LGBTQ youth in a way that shifts all students’ perspectives on agency and social change. In these classes students should learn how marginalized communities and unsung, “everyday” leaders played a central role in pushing for the civil and human rights protections we have today.

An LGBTQ-inclusive ethnic studies curriculum should also be accompanied by social supports at school. The 2020 report found that students who had access to queer-affirming and cultural identity-affirming groups, such as gender and sexuality alliances and Black student unions, were more likely to stay in school. Mentoring programs, job training, access to housing for unhoused Black queer youth and culturally responsive therapy can also bolster academic preparedness.

The ethnic studies mandate is a critical step toward ensuring that all students are exposed to culturally relevant education. But unless the curriculum addresses students’ needs outside the classroom — and offers more than one-off mentions of LGBTQ issues during Pride month — it will be yet another mandate with great promise but limited impact.

Sikivu Hutchinson is a co-facilitator of the Black LGBTQIA+ Parent and Caregiver group and the author of “Humanists in the Hood: Unapologetically Black, Feminist, and Heretical.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.