Op-Ed: How supply and demand have driven the U.S. drug crisis into the ‘synthetic era’

At a party in Venice in September, four people overdosed from what they thought was cocaine, three of them dying before paramedics arrived. The cocaine they used reportedly contained fentanyl.

The deaths were another example of what has taken place across the U.S. over the last few years as we have entered what I call the synthetic era of drugs — street dope made with chemicals; no plants involved. Synthetic drugs of various kinds have been around for decades, but none have come close to the supply and threat of the two staples now coming up from Mexico: fentanyl and methamphetamine. And with synthetic drugs, as with most other products both legal and illegal, supply shapes demand.

I suspect this era will be with us for some time because synthetic drugs make huge business sense to traffickers. They no longer need land, irrigation, pesticides or farmworkers to grow drugs — they can produce them in makeshift labs or industrial warehouses. With no need to plan around weather and seasons, they can make these drugs year-round, provided they have enough chemicals. Synthetic drugs are quicker to make, and in the case of fentanyl, easier to smuggle because so little of it is needed to make extraordinary profits.

As deplorably as Sackler family members are alleged to have behaved, this epidemic was too complex for one group to have created.

Key to the trafficking equation are shipping ports, which provide access to the world’s chemical markets and the ingredients needed to make synthetic drugs. Combine that with the impunity Mexican traffickers enjoy — ensured by corruption in that country and the guns smuggled there from ours — and the result is potent dope in the staggering quantities we see now across the U.S.

The Drug Enforcement Administration reported in September that it had already seized 9.5 million fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills so far this year — more than it had in the two prior years combined. Some 40% of the seized pills had deadly quantities of the drug. Mexican-made meth is so prevalent that its street price has collapsed to the lowest ever seen — typically between $1,500 and $3,000 a pound, down from roughly $10,000 and more per pound less than a decade ago.

A relentless supply is a reason drug dealers mix a hyper-potent drug like fentanyl into whatever they’re selling, even at the risk of killing their customers.

Fentanyl has become so commonplace that dealers now use it the way we use salt on our food. They liberally sprinkle it into anything they’re selling: cocaine, methamphetamine and, in some rare cases, marijuana. They are motivated by the belief that fentanyl can boost the potency of any drug.

This is particularly true of cocaine. Many people across America have been dying from overdoses on cocaine they didn’t know was laced with fentanyl. This has been a major cause of an increase in opioid-overdose deaths among African Americans in particular. Prior to fentanyl the opioid epidemic primarily affected white people.

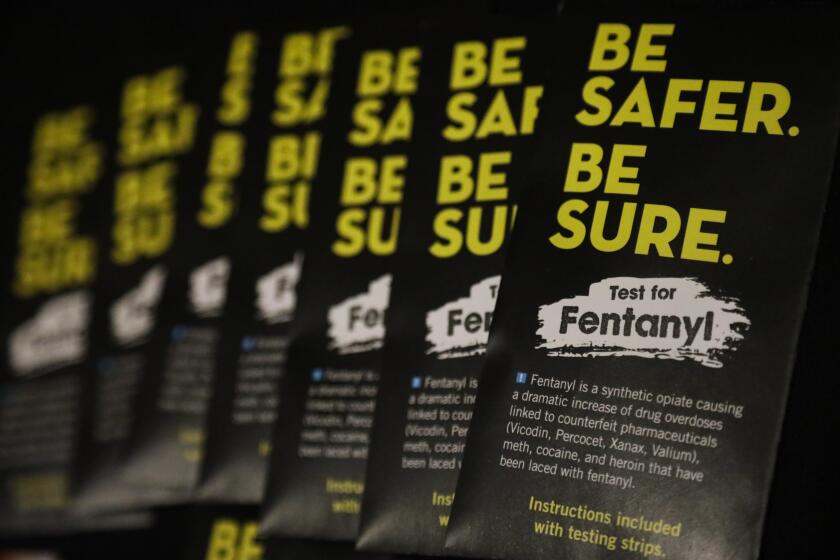

Fentanyl is often accidentally ingested, killing thousands of Americans a year. Home test kits and a readily available nasal spray could help save lives.

Dealers also understand some basic truths about the drug-addicted brain that have emerged from advances in neuroscience in the last two decades. Our brains contain elaborate systems that warn us of danger, of imminent threat of death. Without these systems we would never have survived as a species.

Drugs of abuse have proven to mute these essential systems like nothing else. They hijack these parts of our brain so that they no longer warn us of imminent death. Instead, these complex neural systems, when on drugs, betray us and work in favor of dope, allowing the drugs to convince us we can only function with it alone — even as it kills us. Like a parasite that will kill its host.

Dealers know that to the drug-addicted mind, an overdose is not a warning; it’s an advertisement. An overdose or a death is notice that a dealer has especially potent dope for sale. This is why dealers have determined it makes good business sense to mix fentanyl into other drugs, even knowing that the concoction may kill a customer or two.

For dealers, there is another advantage to adding fentanyl to cocaine or meth: It can turn an occasional buyer into an opioid-addicted daily customer who needs the drug to prevent sickness from withdrawal. And given the competition among dealers created by all this supply, once one dealer adds fentanyl to whatever he’s selling, his competitors must follow suit or they will lose customers.

Many addicts won’t buy any drugs that don’t include fentanyl. One mid-level dealer I met recently gave her wholesaler some fentanyl test strips — which are intended to detect fentanyl and warn a user of its presence. In this case, she wanted the wholesaler to use them to make sure that whatever he bought included fentanyl.

For those addicted to fentanyl, heroin isn’t potent enough to keep the withdrawal sickness away, say many people I’ve spoken to. That is one reason heroin is disappearing from U.S. streets and opium-poppy farmers in Mexico are in crisis as traffickers transition from a bulky plant to an easy synthetic.

Today, street addicts commonly have several drugs in their system, often coming from one source. “What we call heroin has probably got everything but heroin in it,” a user in Eastern Tennessee told me recently.

Today’s quantities of synthetic drugs have brought to an end the era of “recreational drug use.” That concept belongs to a past when drugs were far more expensive, harder to procure and less potent and more forgiving; people could stay alive for decades while still using heroin.

Now, every line of cocaine, every “pill” at a party is an invitation to Russian roulette. On the streets of America, there’s no such thing as a long-term fentanyl user.

Sam Quinones. a former Los Angeles Times reporter, is the author of “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic” and “The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth,” which will be published Tuesday.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.