Editorial: What should female athletes wear at the Tokyo Olympics? Whatever works for them

It was, essentially, an order for the female athletes to show more skin: The Norwegian women’s beach handball team drew a fine for wearing shorts at the European championships last week, instead of sporting bikini bottoms that bare part of the derriere.

Their “improper clothing” failed to meet the European Handball Federation’s requirement that briefs have “a close fit and cut on an upward angle toward the top of the leg.” Midriff-baring tops are required as well, though the team had those.

Sadly, that’s not an isolated example. International sports federations have for too long dictated stringent and nonsensical rules for women about what they may or may not wear during competition. Some women’s teams are wearying of high-cut leotards, bathing suits and midriff-baring (or covering) uniforms. Men are typically given more leeway and more choices.

Some athletes prefer scant uniforms; for example, many female beach volleyball players have said that close-fitting bikinis keep out sand and keep them cool during play. And those players, the best of whom are now at the Tokyo Olympics, actually have options — a 2012 rule change allowed them to choose among various outfits they can wear depending on what serves their athletic, religious or personal needs, as long as members of both teams decide on one style.

But when women do choose skimpier outfits, the cameras have too often focused on a sort of sports cheesecake, with close-ups of their body parts more than shots of their dynamic athleticism.

And then there was the Paralympian who was told during the English championships earlier this month that her briefs were too short. It’s getting hard to win, in more ways than one.

Women athletes have felt pressure to dress one way or another for years. In 2010, female boxers were almost forced to wear skirts to differentiate them from the men, as hard as that may be to believe, but the International Amateur Boxing Assn. backed off. It took longer for badminton officials to drop their 2011 skirt requirement for women. The wince-worthy reason given by one world badminton official: “We just want them to look feminine and have a nice presentation so women will be more popular.” This was well into the 21st century.

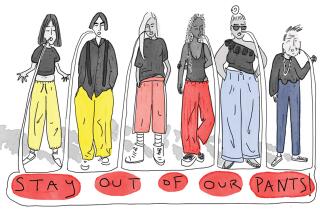

Now the European Handball Federation is proving that sexism is far from dead. And women are getting sick of it. Not just the athletes, but the viewers who see these female athletes of accomplishment being reduced to objects of desire.

At the current Olympics, the German women’s gymnasts chose sharp-looking ankle-length unitards, a deliberate statement about what they called “sexualization” in the sport. The unitards met regulations, but they were different enough from the usual high-cut leotards to draw attention, which was the idea in the first place. Just as important were the statements by team members that the usual leotards were fine, as long as they represented women athletes making their own decisions.

Women — and men, for that matter, though the issue affects them less often — should be able to choose the athletic wear that works for them, as long as it doesn’t give them an unfair competitive advantage. They shouldn’t be called prudes for wearing something that covers more of their bodies, or slut-shamed if they choose something that exposes more skin.

Nor should team members who compete as individuals all have to wear identical uniforms. Colors or graphic design can be used to identify them as coming from the same country, but their performance depends in part on the cut and fit of the clothing. That should make it an individual choice — which includes swim caps for the more voluminous hair of many Black competitors — unless the clothing gives the athlete an unfair advantage. Let’s make it about athletic talent, not about the look.

The Norwegian handball players did more than stand up to rigid and sexist rules. They raised a stink where it needed to be raised. (The Norwegian Handball Federation has said it will pay the roughly $1,800 fine for the team, and pop star Pink has offered to do so as well.)

The Olympics, and the associated federations and agencies that feed into this elite athletics industry, are in danger of becoming the stegosauruses of the sports world with their antiquated and biased rules (let’s not forget how U.S. sprinter Sha’Carri Richardson was booted from her chance at gold over the legal use of some marijuana even though alcohol use is permitted). For their own good, as well as that of athletes and spectators, they need to hoist themselves into the 2020s.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.