Column: Why did the U.S. put Ahmad Chebli on its no-fly list? He deserves to know, and so do we

In its long battle with Ahmad Chebli, the U.S. government finally caved.

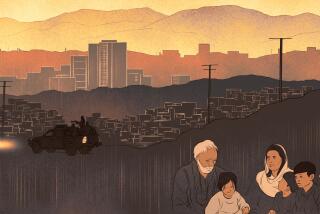

Chebli is an American citizen, born in Chicago, who tried to board a plane in Beirut in November 2018 to return to his home in the United States but was barred from the flight on orders of the American government. No one would explain why. For a month, he says, he was not allowed to return with his family to Michigan, where he works as an engineer in the auto industry.

Eventually he was told that his name had appeared on the U.S. government’s no-fly list of known or suspected terrorists. He was granted a one-time waiver to return home, but he remained on the list. And when he asked — repeatedly — why he was there and how he could be removed, he received no answer. He wrote to the Department of Homeland Security to no avail. He wrote to the FBI but was told their records were exempt from disclosure.

Since then, he has been subjected to heightened screenings and delays to the point of missed flights on the occasions when he has tried to fly domestically. He’s been unable for more than two years to fly to visit friends and relatives in Lebanon or elsewhere overseas.

That is bad enough. But worse yet, Chebli believes he was put on the no-fly list as punishment for refusing to become an informant for the FBI. He says that in August 2018, three months before he was stopped at the airport in Beirut, FBI agents began pressuring him to report to them about people “in his community.” They approached him repeatedly, he says, questioning him about his political and religious beliefs. They accused him of being a member of Hezbollah and having ties to militants, which he vehemently denied. He says he told the FBI agents that he would not spy on his friends and neighbors.

Then he showed up on the list.

Chebli finally sued in federal District Court last month, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union, charging that the government had violated his due process rights when it denied him the ability to travel. He said he’d been put on the list based on vague criteria, he’d been stigmatized as a terrorist, his right to know the reason for his placement on the list had been capriciously denied, and he had been offered no meaningful way to challenge the decision.

Spokespeople for the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security declined to comment for this article, saying they don’t discuss matters involving pending litigation. But 10 days after the suit was filed, the government responded to Chebli.

Without conceding anything, without explaining anything, without addressing any of the underlying issues, the Department of Homeland Security said Chebli no longer satisfied the criteria for placement on the no-fly list and had been removed from it.

That solved Chebli’s immediate problem. He withdrew his lawsuit Wednesday.

”I’m relieved to be off the no-fly list, but still reeling from the government’s abusive use of the list against me and its violations of my constitutional rights,” Chebli said in a prepared statement.

The FBI and Homeland Security, however, shouldn’t get off the hook so easily. Simply because they removed his name, we may never know whether he belonged on the list or why he was unable to get a straight answer when he sought one. If they don’t think he’s a terrorist, why did they put him on the list — and if they do think he’s a terrorist, why did they take him off?

And if he was indeed included as punishment for refusing to become an informant, that’s an outrage that goes beyond mere opacity and obfuscation.

“It’s infuriating that they can jerk someone around like this for two years,” said Hina Shamsi, the director of the ACLU’s National Security Project. “And what they stubbornly refuse to do in case after case and situation after situation is to overhaul their system so it doesn’t violate due process.”

Chebli is not the first person to claim he was put on the list as punishment. Three other Muslim men with either citizenship or legal permanent U.S. residency also sued the government in recent years, saying they’d been added to the no-fly list for refusing to serve as “government spies in their religious communities.” That case is pending.

There are more than 1 million people on the government’s terrorist screening database. Most must undergo heightened screening and security before they can travel by air. But a subset of them — as of June 2016, approximately 81,000, including about 1,000 U.S. citizens — are on the no-fly list, and usually can’t fly at all — to, from, within or over American airspace on a U.S. commercial aircraft.

People are put on the no-fly list if there is “reasonable suspicion” that they pose a threat of carrying out an act of terrorism. The FBI has not explained what constitutes a “threat.” According to government documents, “concrete facts are not necessary” to create reasonable suspicion.

Homeland Security has a “Traveler Redress Inquiry Program.” That’s what Chebli tried to use to get answers, without a substantive response.

Of course the U.S. needs to be able to fight terrorism, and at this point, we have no way of knowing for certain what led the government to blacklist Chebli in the first place. But surely we can achieve security without denying people the meaningful and timely due process they deserve.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.