Op-Ed: Fight the gun violence epidemic like we fight cancer — one small step at a time

While COVID-19 has dominated our public health discussions over the last year, we have failed to adequately address another deadly epidemic.

This epidemic affects more than 300 people every day in the United States and has a fatality rate of about 30%. It claims the lives of more than 3,000 American children and teens per year.

This uniquely American epidemic is one of gun violence.

And just like any public health crisis, there is no one easy fix. Consider cancer. Though we sometimes refer to this constellation of diseases as a monolith, there are, of course, many different forms of cancer, each with its own presentation, at-risk patient populations and modes of prevention.

And though there is no single intervention that will uniformly cut down on all morbidity and mortality due to cancer, we have nevertheless spent the last century and then some working on ways to screen for, treat and reduce the risk of getting cancer, in all its forms.

Biden’s proposals would require background checks for ‘ghost guns,’ encourage state red-flag laws and more. Yet they stop short of what advocates seek.

Similarly, there are many forms of gun violence. And although mass shootings tend to garner the most attention, such incidents actually account for a small portion of firearm deaths in the United States. More common are gun deaths due to suicide, intentional homicide, domestic violence, robbery and assault, and accidents.

And just like cancer, different forms of gun violence predominate in different at-risk populations, present in different ways and require unique modes of prevention. In other words, the same measures that prevent gun violence in the form of suicide are not necessarily the measures preventing gun violence in the form of police brutality. They are different diseases under the same diagnostic umbrella.

No one measure, legislative or otherwise, will mitigate all modes of gun violence, any more than an annual colonoscopy will prevent all deaths due to cancer. Those who argue that a particular strategy is not a panacea and is therefore not worthwhile are missing the point.

For instance, no one would suggest that seat belts eliminate all motor vehicle fatalities. However, seat belts — in conjunction with airbags, DUI laws, improved traffic signals, windshield safety glass and child car seats — have contributed to a fivefold decrease in traffic fatalities since Congress passed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act in 1966.

We know how to do this. We’ve done it before.

And now, we can do it again.

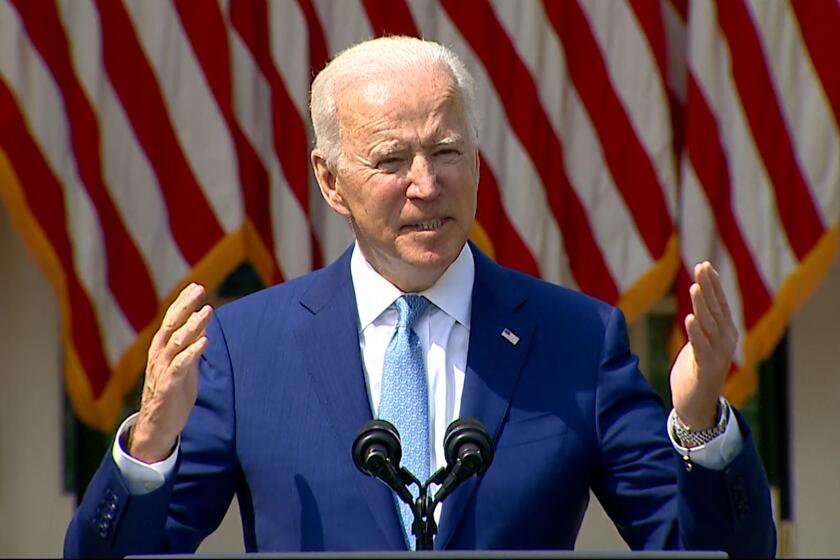

Last week, President Biden presented a series of modest measures to curtail the gun violence epidemic plaguing our country. The action came about three weeks after the horrific shootings on March 16 in the Atlanta area that left eight victims dead. Of those killed, six were Asian women.

When Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris visited Atlanta days after the shootings, I was among the local Asian American leaders who met with them. Many among us made the connection between this appalling crime and the rise in anti-Asian violence in the United States. The president assured us more resources would be devoted to the issue of discrimination and violence against the Asian American and Pacific Islander community — and that he would move decisively to mitigate the threat of gun violence against us.

The executive actions Biden has taken include increasing funding for community violence intervention programs, directing the Department of Justice to stop the unregulated sales of “ghost gun” kits that can be made from parts purchased online, and encouraging states to adopt “red flag” laws that permit family members or law enforcement to petition a state court to temporarily remove firearms from someone who may be a danger to themselves or others.

The president has acknowledged that these incremental solutions are not nearly enough, saying: “This is just a start. … We’ve got a lot of work to do.” Larger-scale measures, like the passage of House Resolution 8, which would require background checks to extend to private gun sales and transfers, would require the support of Congress.

Gun violence is a complicated and intractable epidemic. But we once considered cancer untreatable as well, and most early attempts to treat it were small, palliative and only marginally effective against what felt like an incurable problem. The key is that scientists and doctors didn’t stop there.

When dealing with a public health crisis on the scale of American gun violence, no measure is too modest.

While speaking at the funeral of Xiaojie Tan — who died in the March 16 shootings — Mike Webb, her ex-husband, said her family in China felt that the United States, with its culture of fetishizing gun ownership over human safety, was simply not safe. “What kind of example are we setting for the rest of the world?” he lamented. “Must our flags always fly at half-mast?”

In the wake of the tragedy in Atlanta, the president and vice president promised to take bold actions. And sometimes the boldest move, especially when fighting an epidemic seemingly without end, is simply understanding that effective interventions involve taking one small step at a time.

Michelle Au is an anesthesiologist in the Atlanta metropolitan area and a state senator in Georgia.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.