Op-Ed: Why Dr. Seuss’ evolution is the right lesson for us all

Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the business that preserves the author’s legacy, announced recently that six of his works will stop being published because they “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.”

As a historian, a parent and the owner of a small publishing house, I have found that one of the best ways to teach children that authors change over time is by asking them to put Dr. Seuss’ books in chronological order, since his oeuvre is one of the first that kids can really conquer. It seems this lesson might be a good one for adults right now as well.

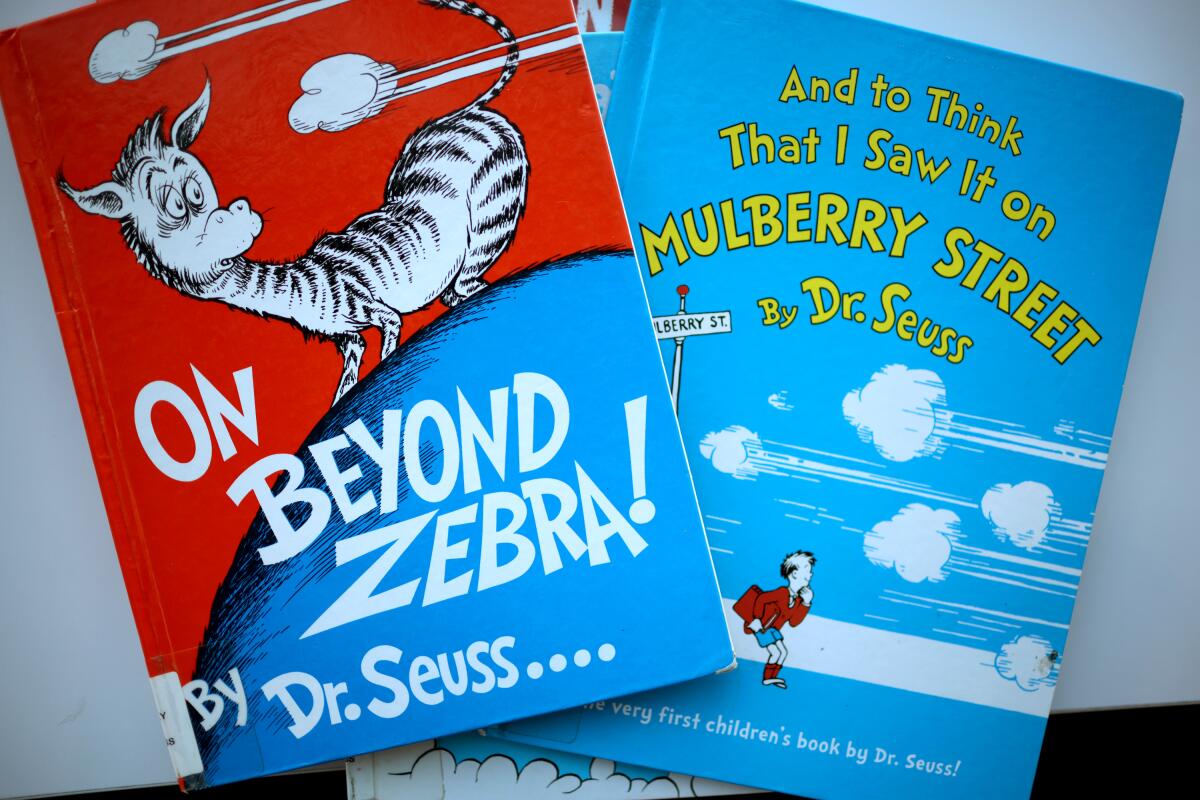

Once you start looking at the Seuss collection, the shifts are hard to miss. Start with the pictures. When Theodor Geisel’s first Seuss book, “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street,” was published in 1937, printing in color was more time-consuming and more expensive. Other early books, such as “The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins” (1938), have little color, and the relatively complex images are coupled with full paragraphs of (gasp!) non-rhyming text.

Later books like “Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories” (1958) have less text and do rhyme, though the palette is still limited to one or two solid colors that don’t mix or overlap, an artifact of the complex color separation process of the time. Subsequent books have additional tells — even Seuss’ unmistakable visual style matured over the years.

What kids might not see, but adults should, is a shift in values. Geisel was a cartoonist before he was an author of children’s books, and racist imagery is present in both bodies of work. But Geisel changed. The six books that will no longer be sold were published in 1937, 1947, 1950, 1953, 1955 and 1976. Geisel died in 1991; the last book he wrote, “Oh, The Places You’ll Go!,” was published in 1990.

Why are many Americans committed to preserving words and images associated with forces bent on preventing fellow citizens from living freely and equally?

It is the later Seuss that is most associated with his ability to distill values into kid-friendly form. The “The Sneetches and Other Stories,” a parable about racism and anti-Semitism, was published in 1961; the environmentalism of “The Lorax” in 1971; and the nuclear non-proliferation of “The Butter Battle Book” in 1984. Geisel clearly had a spark from the very beginning, but there is real development here, and there is a depth to some of these later works that his earliest books lack.

Geisel was also open to revising his older work. Importantly, more than 50 years after publication, Geisel responded to criticism of imagery in “And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street” —one of the six that will no longer be printed — by removing the yellow skin color and pigtail from a character referred to as a “Chinaman.” The changes did not go far enough; the figure, now labeled “Chinese man,” is still holding a bowl and chopsticks.

The point, however, is that Seuss himself recognized problems in the work that brought him fame in the first place. Revisions are not external to his development, but a continuation of it. This willingness to admit to old mistakes is something that we want from the people who speak to our children.

A little more than a year ago, in my role as a publisher, I was given the option to acquire the intellectual property rights to a work that I grew up on, about which I am nostalgic. As I paged through it, trying to get a sense of what a reprint would look like, I noticed for the first time that the work featured sporadic racist depictions of Chinese people. Despite my remembered fondness for the work, there was no way I could justify spreading it further. I did not cancel myself. I simply chose to own up to the responsibility that comes with pushing ideas out into the world.

Mister Rogers, in the later seasons of his show, would sometimes go back and re-record segments of earlier shows. He’d put on the episode-appropriate sweater and erase the mistake of assuming that an unknown person was a he, or that a woman was a housewife.

The ability to reflect on your own mistakes is itself laudable, and it’s one of the things that we try to teach our own kids constantly. Objecting to the news from Dr. Seuss Enterprises on the grounds that it is a revision of the author’s legacy neglects the fact that good authors, authors who listen, are revising their legacy all the time.

David Zvi Kalman is a scholar in residence at the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America and owner of Print-O-Craft Press.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.