Editorial: Rebuilding the refugee resettlement system after Trump poses a challenge for Biden

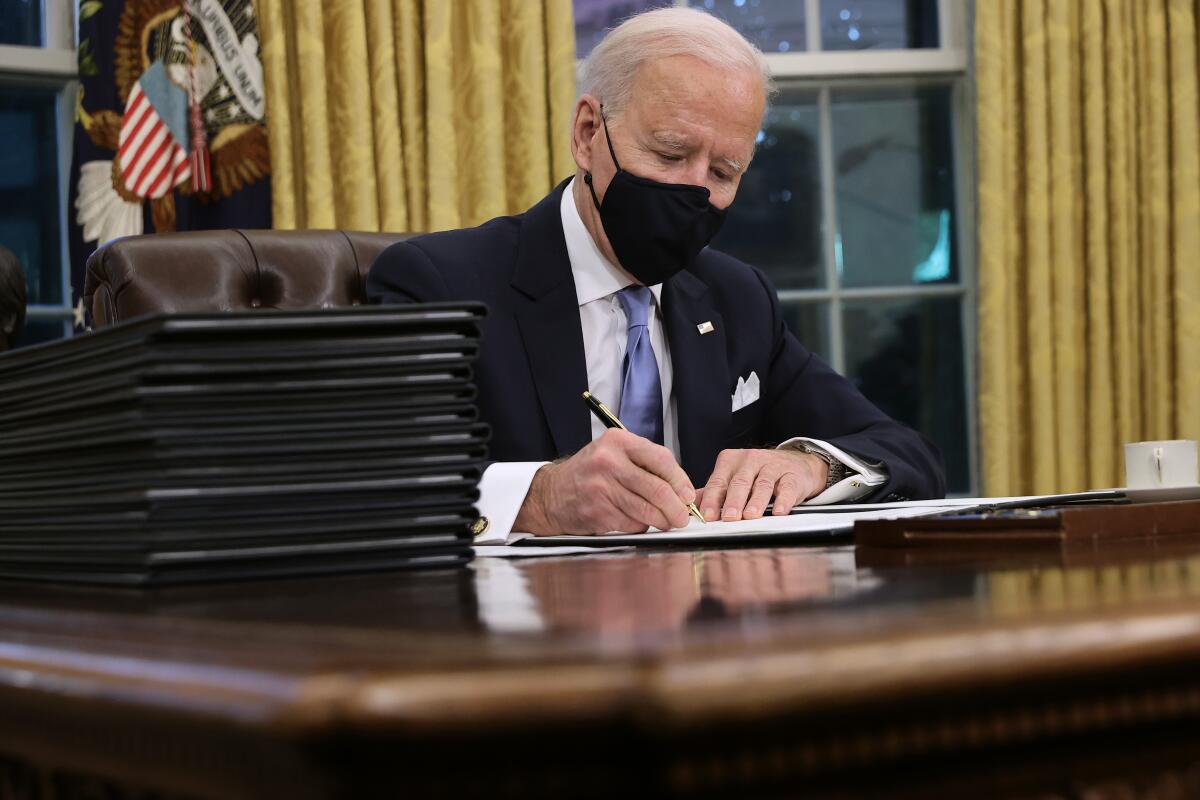

Until immigration hard-liners began running amok in the White House four years ago, the United States stood as the global leader in accepting refugees for permanent resettlement — more than 3.4 million people since the end of the Vietnam War. Among President Biden’s many challenges, as he acknowledged in a speech at the State Department on Thursday, will be to not only regain that status but also to resurrect the collapsed system of nonprofit agencies that do the actual work of resettling the new arrivals. It won’t be easy.

Why bother? Because it is who we are as a nation. Refugees seek resettlement because they do not have homes to which they can return safely, often because they face persecution on account of their race, ethnicity, gender, religion or politics. As a society, we believe in personal freedom, in the right to openly discuss political views without fear of retribution, to hold and express religious beliefs (or to not believe at all), and that all people should be treated equally, regardless of race, ethnicity or gender.

It’s true that the U.S. has never fully lived up to its promise — or its self-image — as a society based on equality and justice, but that does not absolve us of the need to strive for the lofty goals we set for ourselves. And it is just that promise that has made the U.S. the main destination sought by the world’s dispossessed.

Biden’s Justice Department must be above suspicion when it comes to prosecutions

Further, as one of the world’s wealthiest countries (despite our internal economic disparities), we have a moral obligation to help others. We are, by and large, a generous society, though we often squabble over how best to act on that generosity and who deserves to receive it. No, we are not obliged to accept all the world’s dispossessed people, but the U.S. ought to serve as a global role model for how nations should respond to humanitarian crises. It is no small responsibility to be the beacon of hope for those facing despair.

And it is in our national interest. According to a report from the New American Economy, “the high rate of labor force participation of refugees and their spirit of entrepreneurship ... sustains and strengthens their new hometowns.” Refugees were involved in the founding of such businesses as Google, WhatsApp and PayPal, among countless others.

The reality of the global refugee crisis, of course, overwhelms altruism. Some 80 million people currently are displaced, most by war, political instability and drought exacerbated by global warming in the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and Central America. Experts predict that the vast majority of those folks will eventually return home. But for a small subset, returning will be impossible. It is from that pool that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees vets and then recommends candidates to individual nations for permanent resettlement.

Between 2004 and 2016, the year of Donald Trump’s election, the U.S. resettled nearly 63,000 people a year on average. Last year it resettled about 11,800 people, part of a steady downward progression under the Trump administration, according to the Refugee Processing Center. This month Biden reiterated his pledge to reverse the Trump policies and raise the annual resettlement cap to at least 125,000 people, which would be the highest since 1993, and said he would begin working with Congress on the funding to do it.

The federal government accepts refugees (after vetting by the UNHCR and by federal agencies), lends them the money they need to travel to the U.S. and provides a small grant to get them started. But the bulk of the resettling work is done by nonprofit agencies, which draw much of their funding from the federal government based on the number of clients they handle. With so few new arrivals, the nonprofits have been devastated by eviscerated budgets, layoffs and in some cases shuttered operations.

So while it’s good that Biden has pledged to restore refugee resettlements, he also will need to restore the system used to make sure the new arrivals find a place to live, obtain jobs (they receive permission to work) and begin their new lives. It will take time and money to restaff gutted consulates and other federal offices and to reinvigorate the resettlement network that collapsed under a lack of funding during the Trump years.

Without a commitment to transit-friendly communities, Los Angeles will suffer worsening traffic, air pollution and carbon emissions.

Anti-immigrant hard-liners try to portray refugees as a threat to public safety; that is simply not the case. Some resettled refugees have committed violent acts, often after years in the U.S. — such as the people responsible for the Boston Marathon bombing. But they are the exception rather than the rule, and immigrants in general commit crimes at lower rates than native-born Americans.

There are proposals by such organizations as the Center for Migration Studies and the Center for American Progress for building an improved resettlement system to make it stronger, more efficient at integrating refugees and more stable, beginning with changing how it is funded. Such a system needs more reliable multiyear funding instead of erratic per capita payments. And we need better longitudinal studies of outcomes for refugees to help frame future reevaluations.

But, fundamentally, we must return to a posture of acceptance and openness. It is the humane thing to do, and it will make this country stronger in the long run.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.