Op-Ed: Election law can’t protect democracy if our representatives are lawless

Does the Jan. 6 U.S. Capitol insurrection demonstrate that the problems with the legitimacy of American elections exceed the capacity of election law to fix them?

Those of us in the field of election law were no more surprised that President Trump would threaten the peaceful transition of power if he lost the 2020 elections than epidemiologists were surprised by the deadly spread of COVID-19 in a country without a plan for containment. Last April, a multidisciplinary committee at UC Irvine issued a report on how to ensure a legitimate and fair election in 2020. It opened with the observation that “Americans can no longer take for granted that election losers will concede a closely fought election after election authorities (or courts) have declared a winner.”

The report recommended expanding opportunities for early in-person and mail-in balloting; educating the media and its consumers that election results would likely be “too early to call” on election night; and encouraging social media companies to remove unsupported allegations of voter fraud and to direct people instead to reliable sources of information, such as election officials. The UC Irvine committee was not alone in its concerns; other groups focused on questions such as the potential for political actors to manipulate the arcane 1887 Electoral Count Act dictating how Congress counts electoral college votes from the states.

The election itself was a surprising success. Turnout hit record levels. Voter disenfranchisement was rare, widespread voter fraud did not materialize and the election was well-administered except in some isolated pockets. And yet millions of Americans believe the election was stolen.

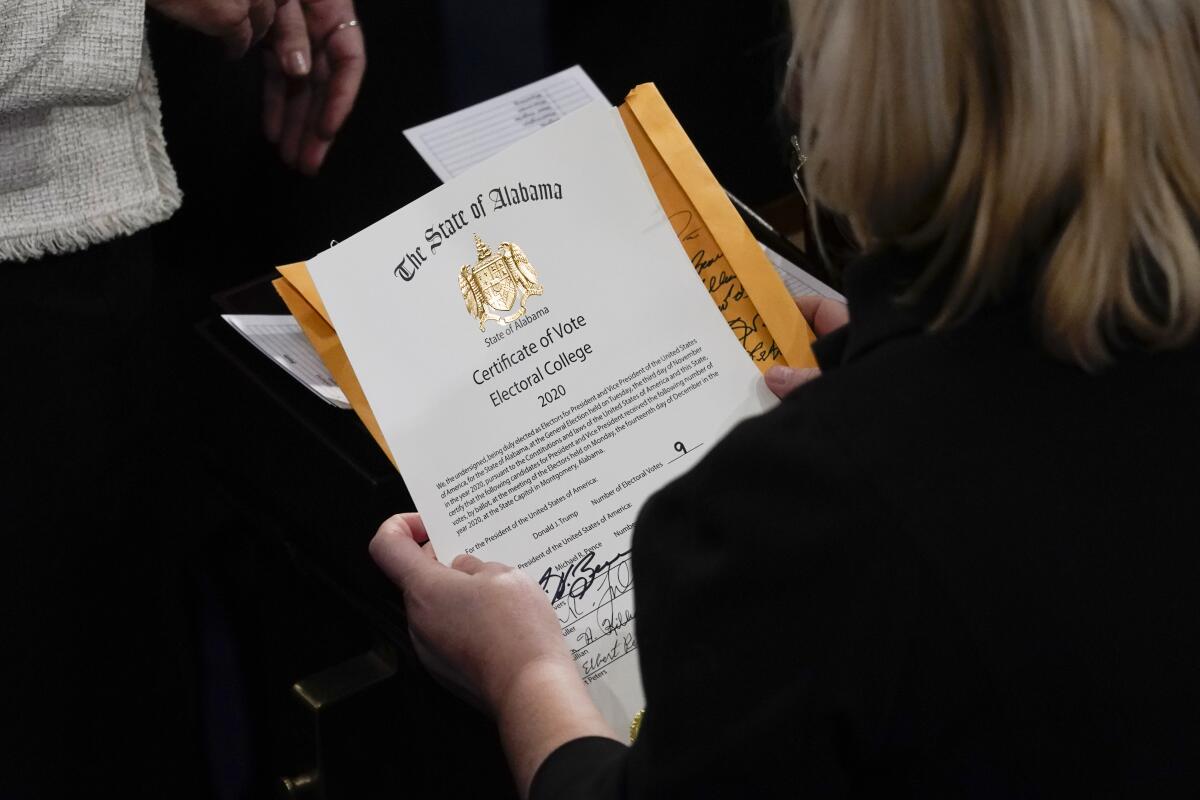

Many of those who stormed the Capitol appeared convinced by Trump’s repeated, audacious lies that voter fraud and irregularities permeated the process. Nearly 150 Republican representatives and senators voted to sustain objections to the vote count in Arizona and Pennsylvania when there is no credible evidence of election irregularities or malfeasance in the country. Trump incontrovertibly lost the election in both the electoral college and the popular vote, but he came perilously close to finding a way to remain in office.

It took the civic virtue of about a dozen Republicans who had some control over the election process to resist Trump’s and his supporters’ incessant entreaties to overturn the will of the people. The president tried to get Georgia’s secretary of state to manufacture 11,780 Trump votes. He pushed state and local canvassing boards to reject election results. He and his allies brought frivolous lawsuits. As Barton Gellman recently explained in the Atlantic, had those virtuous Republicans not resisted Trump’s efforts, we could have had a full-on constitutional crisis, with Congress enabled to vote for sham alternative slates of electors.

These events demonstrate the limits of law in preventing democratic decay. As questions surfaced — could Rudy Giuliani’s claims lead to Pennsylvania’s election results being overturned? What happens if a Republican legislature tries to appoint alternative electors but the Democratic governor objects? Does the vice president have the power to block the presentation of electoral college votes to Congress? — I sought answers taking the law seriously and literally, and I reassured worried citizens that election law offered protections for a free and fair contest.

But the events of Jan. 6 show that at some point we may move outside the realm of law and into the realm of brute power politics and even violence. Had the vice president been killed or the speaker of the House held hostage, niceties about federal jurisdiction, how to handle competing slates of electors, and the precise meaning of the Electoral Count Act would have gone out the window. The actions of the Republicans who rejected valid electoral college votes make me think that if the GOP had held a House majority, they would have ignored the rules and law.

When people fail to obey the law, the law obviously cannot act as a constraint on their behavior. I and others have proposed the legal steps that Congress and states should take to make election law clearer and to remove all forms of discretion to manipulate election results, but these proposals are meaningless if political actors do not abide by legal rules

If the problem is no longer the shape of the law, but lawlessness itself, our democratic system is in serious jeopardy. The Republican Party is going to have to figure out how to expel the Trumpian elements of the party, something very difficult to do when they make up a majority of Republicans in the House and in many state legislatures as well. Pressure coming from the business community and from society at large will help, but it may not be enough.

On Wednesday we will have a transition of power, albeit not a totally peaceful one. Joe Biden, the candidate who incontrovertibly won election, becomes president. But the threats to future democratic elections are huge and obvious. We are far from out of the woods.

Election law expert Richard L. Hasen is a professor at the UC Irvine School of Law. His most recent book is “Election Meltdown: Dirty Tricks, Distrust and the Threat to American Democracy.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.