Opinion: How the Klan and the Hillside Strangler play in to the strange history of L.A. County district attorneys

This is the first in a series of articles about the Los Angeles County district attorney’s race.

Jackie Lacey became Los Angeles County district attorney in 2012 after winning election to an open seat, meaning no incumbent was running to keep the job. That made her a rarity over the last century, beyond being the county’s first female and first Black district attorney. Since the 1920s, the majority of Los Angeles County district attorneys first took office after being appointed by the Board of Supervisors because the incumbents left early. A curiously large number of district attorneys died in office.

Beginning in the 1980s, though, voters began booting out one district attorney after another, following campaigns that were at least as contentious as the current contest between Lacey and her challenger, George Gascón. If Gascón wins, he would be the first L.A. County district attorney to have had the same job in another county.

The 2012 open seat was one of the reasons the Times editorial page called that election L.A. County voters’ “most consequential vote in years.” It had the prospect of resetting the prosecutorial direction of the nation’s most populous county, without it being a referendum on an incumbent district attorney.

Why was that unusual? Let’s go back just a century to find Dist. Atty. Thomas Lee Woolwine in office amid a public conversation about race and racism that resonates today.

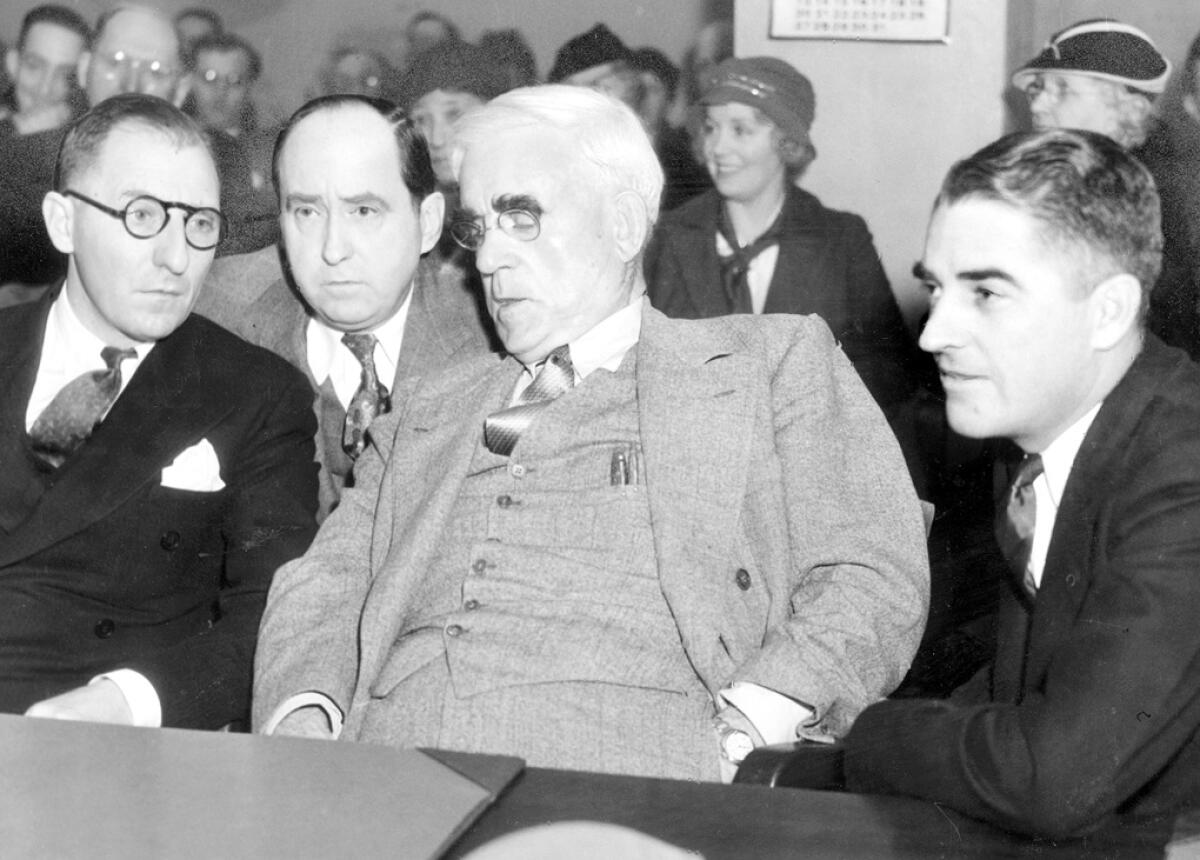

In 1922, Dist. Atty. Woolwine was running for governor after losing one of his biggest cases — against more than 30 Ku Klux Klan members who had raided the Inglewood home of immigrant bootleggers. The district attorney prosecuted the Klan for unlawful entry and attempted murder but lost the case.

Woolwine’s subsequent crackdown on the Klan in L.A. County uncovered the fact that Sheriff William Traeger and L.A. Police Chief Louis D. Oaks were both KKK members. Both said they had resigned from the organization.

In the wake of the acquittal, Klan harassment of Woolwine may have contributed to his losing the governor’s race and falling into ill health. He announced that he was planning to step down and wanted the Board of Supervisors to appoint one of his deputies, Asa Keyes, to fill out the term, but the supervisors leaned toward a different prospective replacement. Woolwine then quietly began to investigate them for graft. They quickly came around and appointed Keyes.

Bad move. Once in office, Keyes also investigated the board and got indictments against all five supervisors. They responded with their own allegations against the district attorney. Keyes was eventually indicted for accepting bribes in an unrelated matter, and he was convicted and served time in San Quentin alongside many of the convicts he sent there, as recounted in historian Tom Sitton’s “The Courthouse Crowd,” describing county government’s first hundred years.

Meanwhile, Buron Fitts (who survived a serious World War I battle injury, a train wreck, two plane crashes and an assassination attempt, and ultimately died by suicide) became district attorney, and although he also was indicted while in office, he was acquitted and served through the 1930s. He ran for a record fourth term in 1940 but was beaten by John N. Dockweiler, the son of the man whose name is given to a state beach (and a post office, before it was renamed last year for Marvin Gaye).

Dockweiler died in office and was succeeded in 1943 by board appointee Fred N. Howser, who had a reputation for associating with gangsters. He left early to become state attorney general (where he was implicated in, but not charged with, bribing other public officials to protect the slot machine rackets), leaving the supervisors to appoint William E. Simpson — who died in office. He was succeeded by S. Ernest Roll — who died in office. The board replaced him with William B. McKesson, one of 31 people vying for the appointment, according to Metropolitan News-Enterprise editor and co-publisher Roger Grace, whose columns on L.A. County’s district attorneys are hands down the most complete and colorful accounts of the county’s top prosecutors. The articles show that these board appointments were not rote affairs but elections in their own right (among the five supervisors), with nominees, campaigns, endorsements and votes.

McKesson beat the odds by neither being charged with a crime nor dying while in office. Nor did he leave early to take another job. When he concluded his second term in 1964, the stage was set for the rare open race for L.A. County district attorney.

It was won by L.A. County Superior Court Judge Evelle Younger, who served through the tumult of the 1960s and oversaw the prosecutions of Sirhan B. Sirhan and the Manson family. He was elected attorney general in 1970.

For the record, I worked for Younger at his law firm, after his retirement from politics, and for Grace, at the Metropolitan News.

To replace Younger, the Board of Supervisors appointed Joseph P. Busch — who died in office.

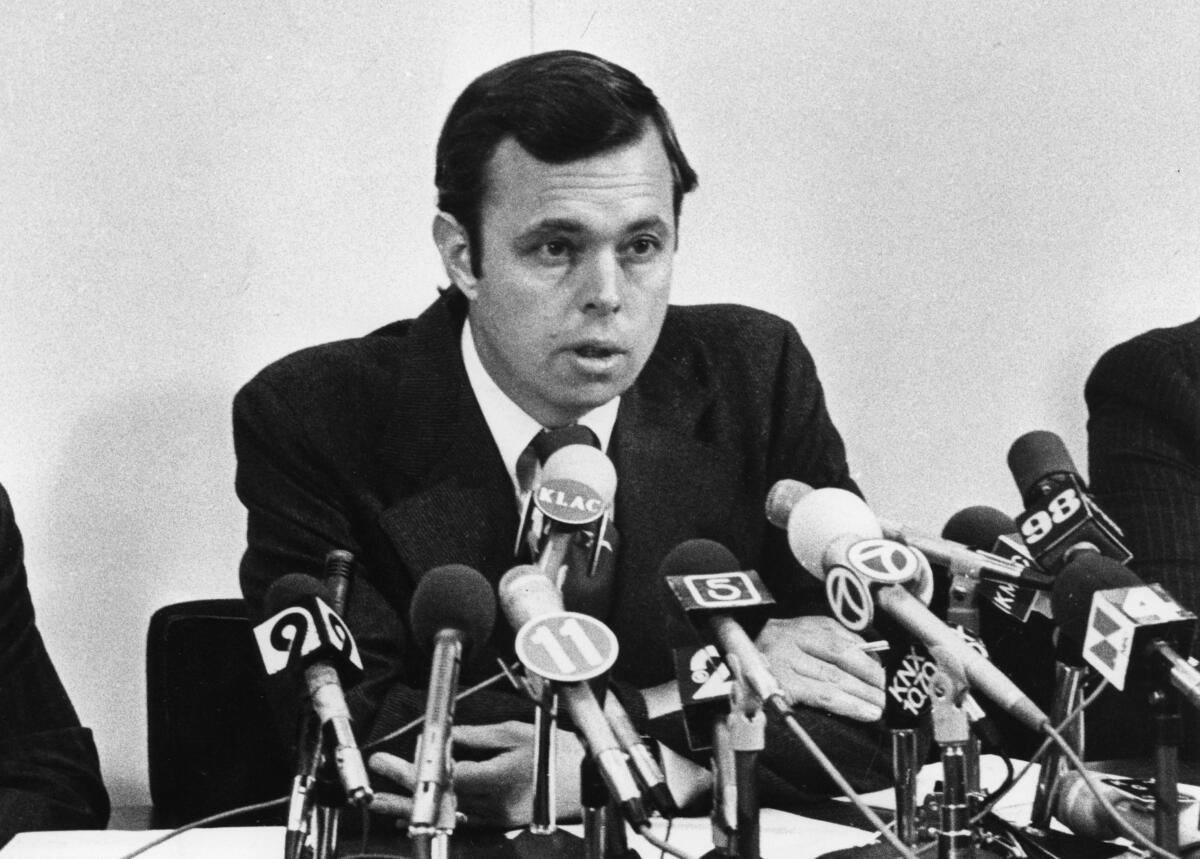

The board then appointed John Van de Kamp, the first federal public defender in L.A. County and later a federal prosecutor. He was elected in 1976 and again in 1980. Widely praised, along with Younger, as among L.A. County’s best district attorneys, Van de Kamp prosecuted a succession of notorious serial killers who terrorized Los Angeles in the 1970s and ’80s: “Freeway Killer” William Bonin, “Sunset Strip Killers” Doug Clark and Carol Bundy, “Skid Row Slasher” Vaughn Greenwood and “Alphabet Bomber” Muharem Kurbegovic.

But he was criticized for attempting to dismiss murder charges against Angelo Buono Jr., one of two serial killers jointly known as the “Hillside Strangler.” The court rejected the dismissal, and the prosecution was handed off to the state attorney general’s office. And then Van de Kamp ran for, and was elected, attorney general and had the case back again. Dianne Feinstein later used Van de Kamp’s handling of the case as district attorney against him when they ran against each other in the Democratic primary for governor in 1990. (Feinstein won but was defeated by Pete Wilson in the general election.)

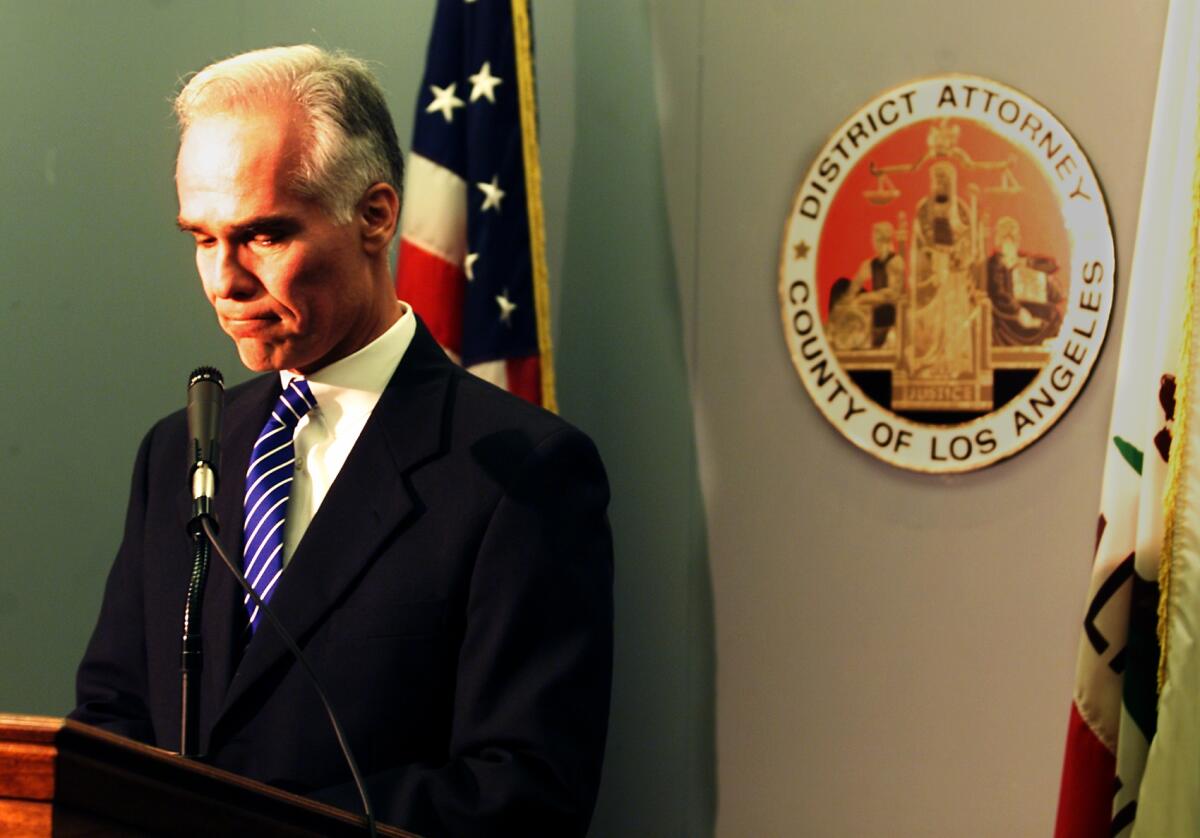

Upon Van de Kamp’s election as attorney general, the Board of Supervisors selected Robert Philibosian, who became the last (so far) district attorney to be appointed by the board and the first of three straight who were ultimately rejected by voters. He was defeated by L.A. City Atty. Ira Reiner, an ambitious and publicity-seeking man known for hard-hitting campaigns and personal attacks. In one of his columns, Grace drew a comparison between Reiner and Woolwine.

Reiner chose Gil Garcetti as his chief deputy and vested him with broad power to run the office — and then proceeded to blame him when things went wrong. When he was elected to a second term, Reiner demoted Garcetti, who understandably nursed a grudge against his boss.

Reiner was heavily criticized for his handling of the “Twilight Zone” case, in which director John Landis was acquitted in 1987 of involuntary manslaughter in the deaths of actor Vic Morrow and two child actors in a movie-set accident; the McMartin Preschool child molestation case, which ended in 1990 with no convictions; and the 1992 acquittal of four LAPD officers in the beating of Rodney King, sparking nearly a week of deadly violence.

Several weeks after the King verdict, Garcetti outpolled Reiner in his reelection primary, paving the way for an ugly runoff campaign. Each candidate claimed to have damaging personal information about the other. Garcetti famously said he had “173 spiral notebooks” detailing conversations between the two men.

Then, in mid-September, Reiner dropped out of the race, cementing a Garcetti victory. But the district attorney’s office continued to be haunted by the impression that it could not win a high-profile prosecution. O.J. Simpson was acquitted in 1995. Several years later, Garcetti and LAPD Chief Bernard C. Parks accused each other of mishandling investigations into the Rampart police corruption scandal.

In 2000, Garcetti was defeated by Steve Cooley, who became the first Los Angeles County district attorney since Fitts to serve three full terms. Although he was defeated by Kamala Harris in the 2010 attorney general race, Cooley also became the first L.A. County district attorney since McKesson in 1964 to leave office, alive, without either stepping down early to take a new job or being defeated for reelection.

Lacey succeeded Cooley in 2012 and was reelected without opposition in 2016. Two of Lacey’s deputies challenged her for reelection last year, but both dropped out soon after Gascón resigned his post as San Francisco district attorney and challenged Lacey in the current race. We may know in less than a week whether Lacey will join Cooley as one of the few three-term district attorneys or if she will instead join Philibosian, Reiner, Garcetti and all the others thrown out by voters.

The progressive (or 21st century, or reform, or modern) prosecutor movement is not securely tied to gender or race, or even to political party.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.