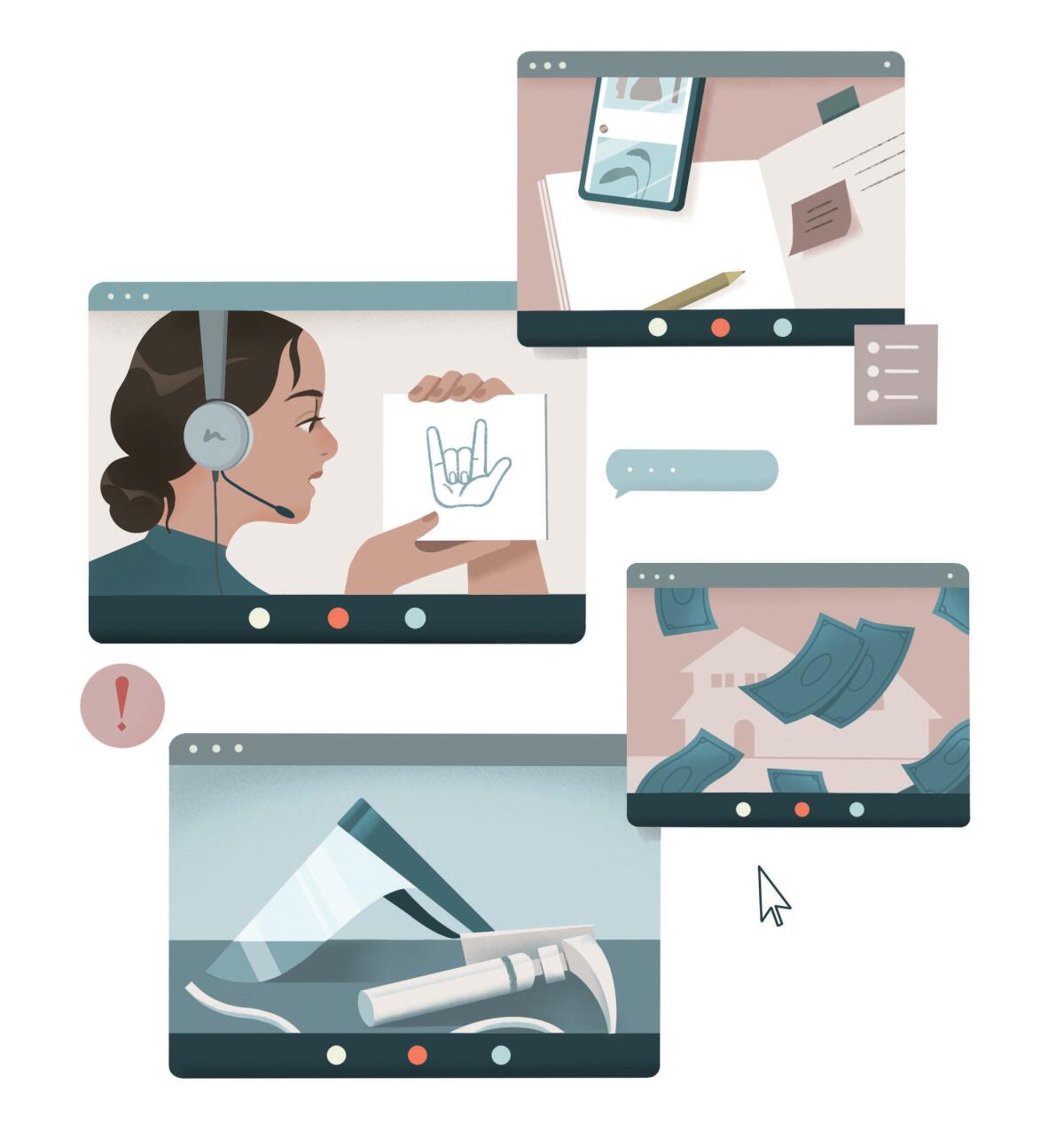

Op-Ed: I was laid off and denied unemployment. Now I could lose my home of 15 years

Across the nation and the world, lives have been drastically altered by coronavirus. In our series “dispatches from the pandemic,” we feature the stories of some of them. You can read Part 1 and Part 2 of the series here and here. If you have something to say about how the outbreak has affected your work, your family or your life (in 400 words or fewer), please tell us here.

Underachieving in confinement

How can a disease I don’t have make me feel so lousy?

In the best of times — the before times — the accomplishments and fascinating lives of my friends, colleagues, and students on social media could be overwhelming. I didn’t begrudge them their successes exactly, but only because I could tell myself that as soon as I had time, I too would write an annotated version of “War and Peace.”

In the meantime, I had the whole outside world as my excuse. I had to teach my class, run errands, lunch with friends, take long hikes with the dog.

Now I have no excuse. I am home every day. I work, but it doesn’t take me very long to get from bed to the kitchen table. It’s not like I have to shower, get dressed and drive 45 minutes to teach. I stay in my sweatpants. I brush my hair only if I feel like it. I have buckets of time, yet I’m still not getting anything done.

Instead, I’m reading Instagram posts about all the clever and creative projects being done by people who are also stuck at home but using the time to accomplish things. One friend is cooking elaborate, many-course meals. Another is sewing bright, cheerful face masks with matching hair ties. Another is baking complicated desserts. An impressive overachiever has built a DIY raised-bed garden in her yard complete with a drip irrigation system she put in herself.

It seems all my friends are making funny videos and amazing craft projects, taking classes in history or astronomy, and writing and performing songs — on new instruments they are teaching themselves to play.

Meanwhile, I stare out my window at the bird feeder. I haven’t managed to clean out a closet, organize my desk or read even one issue of the New Yorker. It is all I can do to walk my dog around the block.

I can’t complain. My daughter came home from New York just before things got really bad there. I’m lucky that she and my son and his wife and my husband and his mother — who is living with us for now — are all healthy.

I have learned to use Zoom, so the class I teach continues. I view it as an accomplishment that in these close quarters I haven’t killed my husband or his mother. That’s something. And the other night I made tortillas. They were a little thick, sort of lumpy, and more the shape of Australia than round, but I did it.

I try to remind myself we are in uncharted waters. None of us has ever been here before, and we are dealing with it in our own separate ways. Some of us get creative. Some of us can’t do anything but hit refresh on the newsfeed. Maybe, for me, it’s enough just to be a witness to this crazy time.

Still, I can’t help feeling I’m failing at the global pandemic.

--Diana Wagman

Wagman is a Los Angeles novelist.

Kids in need

As a teacher in the Los Angeles Unified School District, I applaud the efforts that my colleagues, parents and the district are making to keep students learning during these strange times.

But I know that, for my students, it’s not that simple.

The seven kids in my class have moderate to severe intellectual and developmental disabilities. They range in age from 13 to 22, and they cannot read or write. Most of them can’t talk. Some use special devices to communicate, some use some sign language and some just use gestures, which the adults in the classroom have learned to understand through familiarity and context.

I have four amazing paraprofessionals who work in my class, and as a team we provide constant direct instruction and support, including frequent help with personal hygiene. Our students are never going to go to college or have impressive careers, but every day they amaze us.

Take Lily. When she came to my class, Lily (not her actual name) would push everything in front of her away, and usually right off the table. She put just about everything in her mouth except food, which she threw on the floor. She didn’t talk. She didn’t interact. Her parents are wonderful, and her dad told us wistfully how he hoped one day she would say “Papa.”

It took us about a year to figure out how to reach Lily. Since then, progress has been slow but steady. Today, she comes into the classroom, independently puts away her backpack and gets her morning work. She matches pictures. She matches coins to purchase a snack for herself. She says, “Hi!” and, “Imagination!” She counts with her classmates. She knows about a hundred words in sign language. And she now says the word “Papa.”

This is not a miracle. It came from getting constant reinforcement from a team of adults she trusts and loves and a group of students she engages with seven hours a day, five days a week. We cheer when she puts her bowl in the sink. We clap when she matches coins. We respond when she uses a word. When she laughs, we laugh.

But the things that have worked with Lily and my other students don’t translate to virtual learning.

It’s not that there’s no value in the Zoom sessions we have been doing. The students have loved seeing each other and connecting by laughing and waving, but it’s impossible to do an actual activity.

I also worry about how my students’ families are coping. Having a young adult with severe disabilities is often trying, and school is a welcome respite for parents and siblings. I know they are exhausted.

I’m trying to find meaningful ways to teach during this time, developing curriculum-based activities that families can manage and trying to come up with ways to engage students virtually. I am also looking ahead and trying to create new content that the students will be excited to return to when this is all over.

But it’s going to be a hard month or two or three, and it’s frustrating to think about the progress being interrupted — or even reversed — with kids who have worked so hard for every small gain.

--Barbara Lempel

Lempel teaches at a Los Angeles high school.

An ‘air hungry’ patient

I intubated a woman today. I did it looking less like a doctor and more like an astronaut in unfamiliar territory since I was wearing full head gear with a powered air-purifying respirator, or PAPRs, to shield me from contaminants in the air.

The patient was taken by ambulance to the emergency department where I work in Fresno because she was having trouble breathing. In trying to diagnose her condition, I considered an asthma flare-up as well as congestive heart failure … and then the X-ray showed a dense haziness in both lower lungs that suggested an atypical pneumonia. COVID-19 suddenly rose to the top of the list.

Over the next few hours, her breathing became more rapid and labored. Despite being 86 years old, she was able to breathe on her own longer than I expected. Without intervention, she would most certainly stop breathing and die. In addition to medication, I would normally use bipap — a machine with a mask that pushes air into the lungs to help decrease the work of breathing. That machine wasn’t an option because it scatters micro-droplets and could spread the coronavirus.

It’s hard to watch someone decline without being able to use every tool I have. I conferred with my colleague about other options besides intubation, which is life-saving in the moment but often increases the overall chance of death. He replied, “Get her to change her code status.” Translation: Get her to agree to die. Appropriate perhaps for some; ridiculous for a woman who still walked two miles a day. Still, a sobering reality.

I chose to intubate her when she showed signs of being “air hungry” and her breathing rate decreased. It was clear she was tiring, and I knew it was a losing battle. So I put on all the protective gear, including the otherworldly PAPRs. It’s quite a spectacle. And I did my duty.

As I was suiting up, I got a little emotional thinking, “Is this really happening?” Unfortunately, I fear it’s going to be the new normal as we fight this virus. It’s emotionally hard to intubate someone who is alert and active — and wants to be kept alive. She had told me: “I have some more years to go yet. Do everything.”

I hope she survives. I just don’t know.

After work, I find that I’m not as transparent as I usually am with my husband and family. I didn’t expect to feel this way. Even though I am incredibly sad and lonely, I realize discussing the events of my day will only alarm those I love. How do I share all of this? I can’t. Instead, I keep all these things in my heart. So I don’t tell them, at least not everything.

And they don’t really ask. I don’t think they even know where to begin.

--Camie J. Sorensen

Sorensen is an emergency medicine physician in Fresno. Days after writing this, she learned her patient had died.

Mortgage woes

My wife and I have lived in our house in Sherman Oaks for 15 years, making the mortgage payments every month, in good times and bad. The house, which we share with our two English mastiffs, represents the bulk of our savings. Now those savings are under threat.

I work in patient services for a medical company that provides elective surgeries, and with most elective procedures canceled, I’ve been laid off for the duration of the coronavirus crisis. My wife is an interior designer, and she’s been laid off, too. Her clients have delayed or canceled jobs because they are understandably worried about having workers in their homes while coronavirus is raging.

Because the bulk of my wife’s work is for a firm, and she was an employee, she quickly qualified for unemployment, which will help. I am an independent contractor, so technically am self-employed. My application for unemployment was denied, though I am appealing that decision.

When we called our mortgage lender to see if we might qualify for a payment reduction during the time we’re out of work, they offered something that at first sounded great: suspension of payments for three months. Then we read the fine print. Yes, we wouldn’t have to make the payments now, but in three months, the bill for them would come due.

That sounds terrifying. We have no way of knowing whether we’ll have our jobs back in three months, and even if we do, we aren’t going to get a sudden infusion of cash that will cover three months of back mortgage payments. We worry that if we take this deal, we’ll be facing foreclosure down the road.

In New York, Gov. Mario Cuomo has asked lenders to suspend mortgage payments for three months to customers facing financial stress because of coronavirus. Under his plan, repayment would be tacked onto the end of the mortgage, so people would simply take a bit longer to repay the loan. That sounds entirely reasonable.

My wife and I are doing what we’ve been asked to do. Staying in much of the time. My wife fights the boredom with jigsaw puzzles and old movies; I’ve done some catching up on old sports and organizing of the garage. We walk the dogs — maintaining 6-foot distances from any neighbors we see — and go out to market as needed.

And we worry.

We need the kind of relief Cuomo has called for in New York in California, too.

--Paul Morris III

Morris is sitting out the coronavirus crisis in Sherman Oaks.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.