Op-Ed: We weren’t ready for coronavirus. Now we know what Washington has to do before the next outbreak hits

The coronavirus presents a challenge for the United States the likes of which we haven’t seen in a generation, but one that has been warned of at least since 9/11.

Congress quickly passed three bills to help limit the spread of the virus and assist families and workers who are suffering, including the Senate’s massive economic stimulus awaiting House approval Friday.

But as we address the acute symptoms of this crisis — illness and death, but also social isolation and financial devastation — we must think ahead to how we will confront future epidemics and pandemics. We already can take lessons from the tragedy of the coronavirus crisis and the coalition building it has inspired.

First, we have clearly seen that neither our government nor our healthcare system was prepared for something like COVID-19. Congress can and should play a pivotal role in making sure necessary changes are made. This means assessing federal government structures that worked and those that failed, and instituting reforms and new processes and policies to confront future threats.

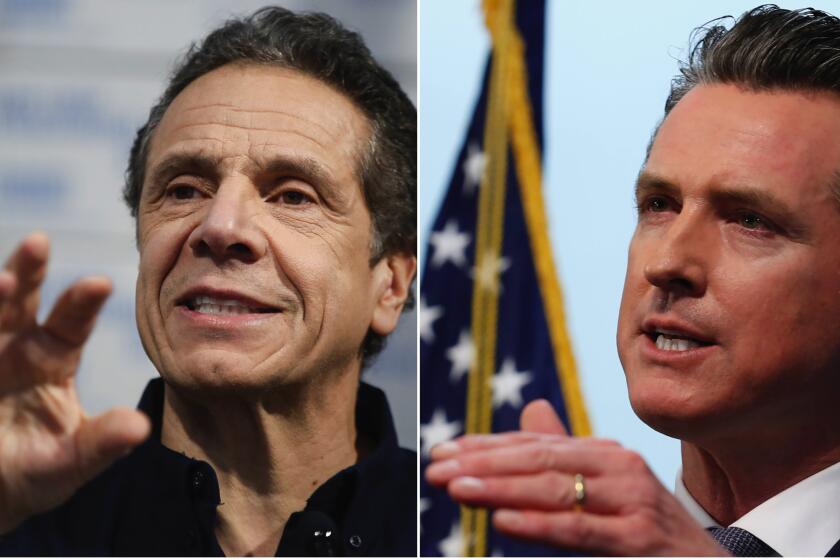

Even Washington experts fear contradicting the president. Our national leaders are the coastal governors now.

The United States has a lot of experience at just this sort of response, most notably in the national security field. After World War II, Congress passed laws that redesigned our security apparatus by establishing the National Security Council, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the CIA.

Similarly, after 9/11, Congress passed laws that dramatically changed how the U.S. confronts terrorism at home and abroad. The Department of Homeland Security was established to discern and secure us against domestic and international threats. The National Counterterrorism Center was created to address gaps in the nation’s international anti-terrorism efforts.

These post-WWII and post-9/11 reforms are templates for grappling with pandemic. For example, the integration and information sharing that was put in place after the devastating attacks of 9/11 provides a model for how we should share information about infectious diseases domestically and with our allies.

Likewise, the role of the director of the National Counterterrorism Center offers a model for a new position: director for combating infectious diseases. Appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, this person would be tasked with advising the White House on all matters related to infectious diseases. He or she would also oversee a new interagency, whole-of-government “center” aimed at preventing, detecting, monitoring and responding to major outbreaks such as COVID-19.

This Center for Combating Infectious Disease would combine analytical and operational functions, ensuring national preparedness for massive domestic and global health emergencies. It would have the authority to gather and disperse information required for a coordinated government response. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would provide it with data and expertise, but so would every other relevant national agency.

If government is going to restrict your constitutional rights, however compelling the emergency, the courts will demand more than a slapdash order.

For example, among its first acts would be the creation of a constantly updated, refined and monitored disease database. It would track the inventory of personal protective equipment in the national stockpile, identify which entities in the private sector should be called upon to augment critical supplies, and set rules requiring other countries to share information in order to get information.

When there’s an outbreak, the public and government would have a single, authoritative source to go to learn symptoms of a disease, how to prevent its spread, and what to do if they feel sick. It would consolidate information regarding travel restrictions, stay-at-home orders and “essential work” directives.

In addition to this new national security center for combating disease, we must collaborate internationally to leverage resources and expertise, much as we do when confronting other global threats such as terrorism and nuclear proliferation. If we wait to prepare for the fight against disease until it shows up on our doorstep, it will be too late.

This will call for strong diplomatic outreach to drive data sharing and actions, from disease detection to the development of antivirals and vaccines. Just as after WWI, the U.S. and other nations established the U.N. with the aim of maintaining global peace and security, we need a similar global response to meet the worldwide pandemic threat.

Our outreach must include capacity-building in Africa, Latin America and southern Asia, where there are deficits in health infrastructure: funding the construction of hospitals and clinics, training healthcare workers and establishing ways to monitor disease patterns and track early indicators of potential outbreaks everywhere.

In our globalized world, international borders cannot contain the likes of the coronavirus. It is up to the United States to lead what must be an international effort against epidemics, helping others as they need it. This is our historical role, and it is in our national interest: We too, may eventually need help from others.

I hope we never see a pandemic like the coronavirus again. But experience tells us that a similar outbreak is more likely than not. It is not too soon to analyze the lessons of the current crisis, in order to be ready for the next one.

Dianne Feinstein is the senior U.S. senator from California.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.