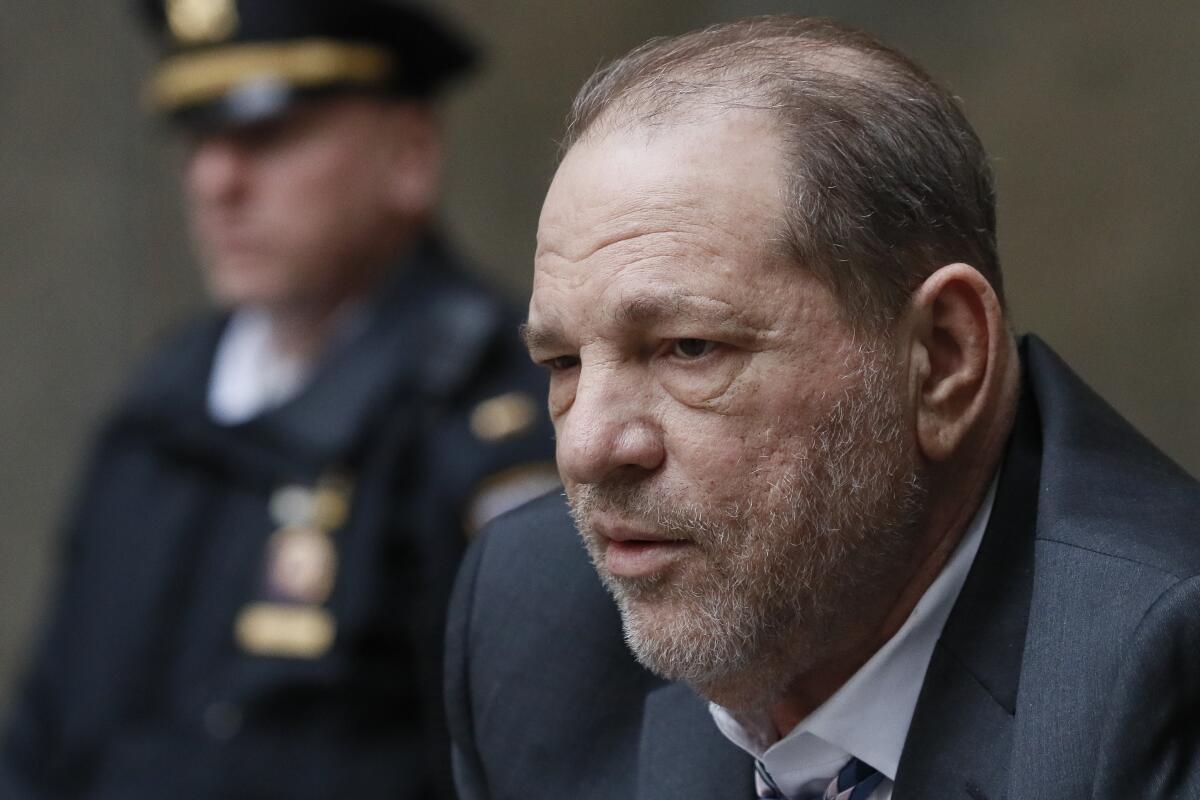

Op-Ed: Jurors saw Weinstein for the monster he is. Here’s why that’s a crucial breakthrough

The Harvey Weinstein jury verdicts leave us with one big question. How could the jurors find Weinstein guilty of rape in the third degree and criminal sexual assault, and yet acquit him of being a serial sexual predator? Don’t the two convictions show that Weinstein was obviously guilty of the predatory sexual assault charges as well?

The ability of jurors to see through Weinstein’s “blame the victim” defense was a great achievement. The rape and criminal sexual assault convictions mean Weinstein probably will go to prison for a long time. But the sexual predator charges were the only ones that carried a life sentence. Other charges loom in Los Angeles. In the meantime, what explains the mixed verdicts in New York?

The jury found Weinstein guilty of raping Jessica Mann and criminally sexually assaulting Miriam Haley. This was a considerable achievement, because juries in the past have bought the “blame the victim” defense Weinstein offered. Weinstein couldn’t have raped Mann, or forced himself on Haley, his lawyers argued, since each kept in contact with him afterward. The implication was that no rape victim would do that. Nor supposedly would they have gone on to have consensual sex with him, or continued to send friendly emails, some even marked “lots of love,” or still worked together on scripts.

Sexual assault cases in which the accuser has continued contact with the alleged perpetrator typically result in acquittal, if they are prosecuted at all. The New York Times described the district attorney’s decision even to bring the case before a jury as “unusually risky” because Mann and Haley had continued communications and agreed to have sex with Weinstein after the assaults. The assumption is that jurors would find such circumstances too complicated to convict. The director of a Chicago group that supports victims of sexual assault said that trying such cases is “practically unheard of.”

And yet, the Weinstein jury smartly saw through this defense. The prosecutor called experts to help jurors understand how rapists overwhelm their victims psychologically, as well as physically. Forensic psychologist Barbara Ziv testified that it is common for women not to report a rape to law enforcement, to deny, compartmentalize, or otherwise try to regain control by maintaining a relationship with their assailants. Rape victims behave in ways that are counterintuitive to a layperson’s expectations. As Ziv testified at the Bill Cosby trial, “most women who were sexually assaulted by someone they know have subsequent contact with that individual.” They undertake a “powerful job” to “normalize” their lives, which sometimes includes continuing to see their assailants, if he was a friend before the assault.

In the case of Weinstein, there was understandable fear that he would ruin the career prospects of any woman who went to the police. Haley explained that, instead of being pro-active, she wanted to “just put it away in a box and pretend like it didn’t happen.”

What the jury understood, by convicting Weinstein, was that all of us need to update our image of the rapist. Weinstein was a monster, but he wasn’t the stranger in the bushes monster. He was the monster in the office, the hotel or the dorm, the one who is capable of committing rape in the context of ongoing relationships. For the jury to have understood this, and convicted Weinstein, is an important turning point.

Nonetheless, the jury stopped short of convicting Weinstein on the predatory sexual assault charges. Under New York law, the jury was asked to go through a complicated two-step process. First, jurors had to decide whether to convict Weinstein of the primary charges — rape of Mann and criminal sexual assault of Haley. Once they found Weinstein guilty of those charges, the jury next had to consider whether to enhance a defendant’s guilt by finding him also guilty of being a sexual predator. But this enhancement required evidence that Weinstein had raped or sexually assaulted at least a third person. Annabella Sciorra testified that she had been raped by Weinstein in the winter of 1993-94, which could establish the necessary pattern.

From notes they sent to the judge during deliberations, we can tell the jury clearly was reviewing and weighing Sciorra’s testimony. But in one note, the jury asked why Weinstein had never been charged with raping Sciorra. The judge’s response was not helpful: “You must not speculate as to any other charges that are not before you.” It would have been clearer to explain that the statute of limitations prevented prosecution of Sciorra’s allegations.

Here the jury may have gotten understandably confused. Even though they were not being asked to find Weinstein guilty of raping Sciorra, they nonetheless had to decide that he had in fact raped her if they were going to tack on a predatory sexual assault conviction to the rape and criminal assault counts related to Mann and Haley.

It may have seemed odd to jurors that they were being asked to punish Weinstein indirectly on the Sciorra case. The acquittal on predatory sexual assault should not diminish the importance of a verdict that shows jury trials can bring rapists to justice.

Jeffrey Abramson, author of “We, the Jury: The Jury System and the Ideal of Democracy,” teaches jury trials and constitutional law at the University of Texas School of Law.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.