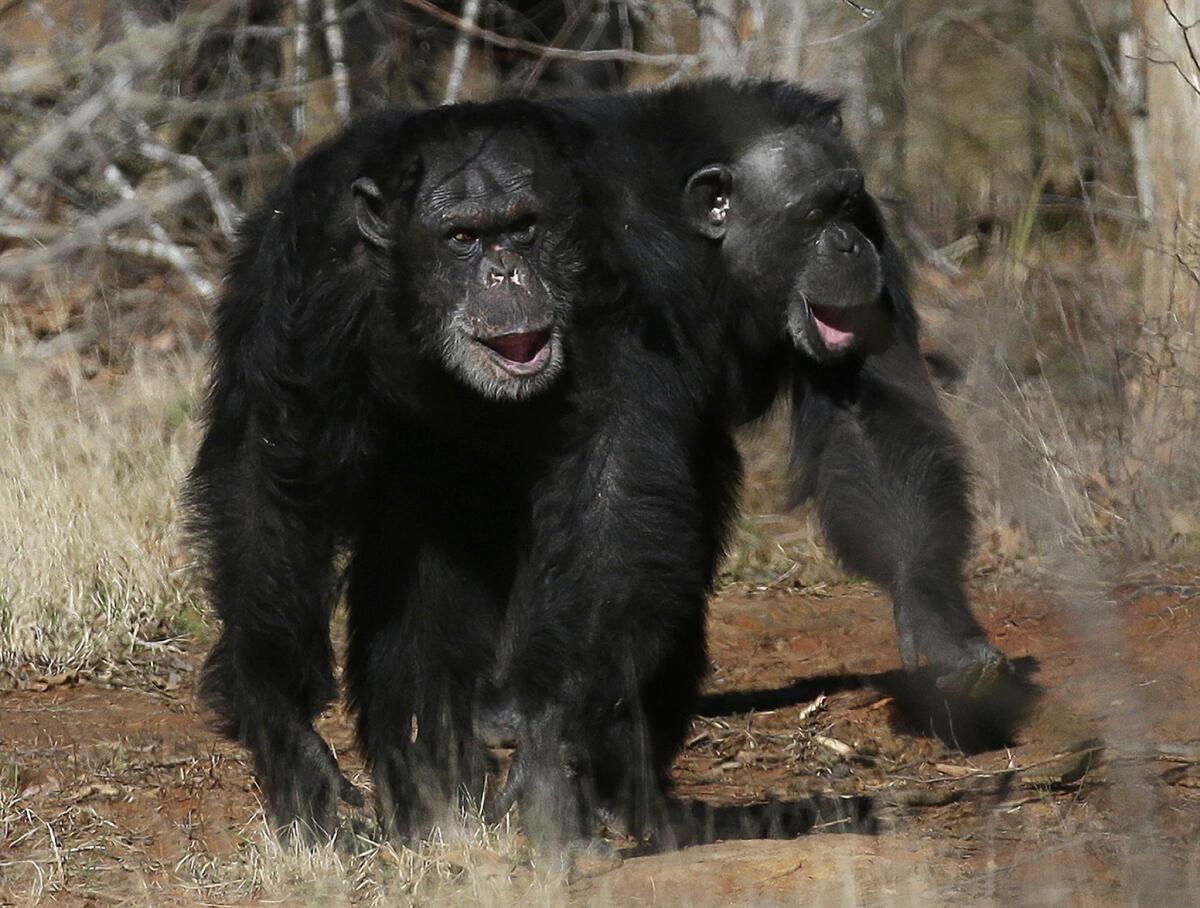

Opinion: How we treat old chimpanzees — and what that says about us

The National Institutes of Health announced last week that it will be breaking its promise to move 44 chimpanzees currently being held in a biomedical facility in New Mexico to Chimp Haven, a sanctuary in Louisiana. Francis Collins, the head of NIH, said a review panel had determined that these chimpanzees are either too old or too sick to relocate safely. This is bad news for the chimpanzees. It also reflects a troubling reality about all research on nonhuman subjects.

There are two main problems in this case. The first is that the process for making this decision was bad, and so the decision might have been bad too. This panel included only NIH veterinarians without any external ethicists or sanctuary experts. Even if these panelists are all highly qualified veterinarians who care deeply about the chimpanzees, they lack relevant expertise and independence.

The second problem is that, even if the decision was right for some chimpanzees, this shows that the NIH very likely made mistakes earlier in the process. In the case of chimpanzees who are too old to move, why wait to move them so late in the process? In the case of chimpanzees who are too sick to move because of the effects of research and confinement, why not anticipate these effects and plan accordingly? Granted, it might be that some chimpanzees are too sick to move for independent and unforeseeable reasons. But how many is that likely to be?

If this decision holds, 44 chimpanzees will spend the rest of their lives at a biomedical facility. They will never experience the kind of care, autonomy or social bonding available at a sanctuary with nearly 300 chimpanzees living on 200 forested acres. Transfer to Chimp Haven may not make up for years of confinement and exploitation, but it is all we can offer them now. It is imperative that NIH revisit its decision to make this outcome possible.

I wish I could say that this is an isolated case, but, unfortunately, this is exactly how the vast majority of decisions are made regarding research on nonhuman subjects.

There is little meaningful regulation for this type of research. For example, the Animal Welfare Act protects some animals in some ways, such as by regulating how some animals are obtained, housed and treated. However, the AWA exempts birds, mice, rats and fish, who make up 95% of nonhuman research subjects. Additionally, even for the animals the AWA protects, it does not protect them enough to rule out harmful, invasive and non-therapeutic research that ends in either permanent captivity or death.

There is also little meaningful oversight, which takes the form of institutional animal care and use committees, self-regulating bodies that determine whether proposed animal use is necessary. Typically, most committee members are scientists or veterinarians, who may lack relevant expertise and independence. There is also a non-scientist and a community member, but in most cases they are neither able nor willing to veto unethical research, including research that harms and kills animals even when humane alternatives are available.

Finally, there is little meaningful care for animals after research is complete. The vast majority of nonhuman research subjects are either kept in captivity or, more likely, killed. This is partly because we lack the resources or infrastructure necessary to care for that many animals, and partly because we determine that relocation would be bad for them. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: We confine or kill these animals either because we failed to arrange for better care or because we treated them so badly that better care is a nonstarter.

What happens to these chimpanzees matters because these chimpanzees matter, and because this case is sadly representative. Whether or not we agree that harmful and invasive research using nonhuman subjects is ever acceptable, we should at least be able to agree that it is not acceptable for us to exploit them so thoroughly that, afterward, we have no choice but to keep them confined or kill them. It is also not acceptable for the institutions that benefit from these practices to be the same institutions that evaluate them.

We use 100 million animals per year in research. Every one of these animals, including the 44 chimpanzees currently being held in New Mexico, is an individual who deserves to be treated with dignity.

We seriously wrong animals when we use them for research without sufficiently considering their needs during or after this research. And, if we use so many animals that sufficient consideration for their needs is impossible, then that provides us with a powerful additional reason to reconsider our use of these animals in the first place.

Jeff Sebo is clinical assistant professor of environmental studies and director of the Animal Studies M.A. Program at New York University. He is co-author of “Chimpanzee Rights.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.