How to honor Trayvon Martin

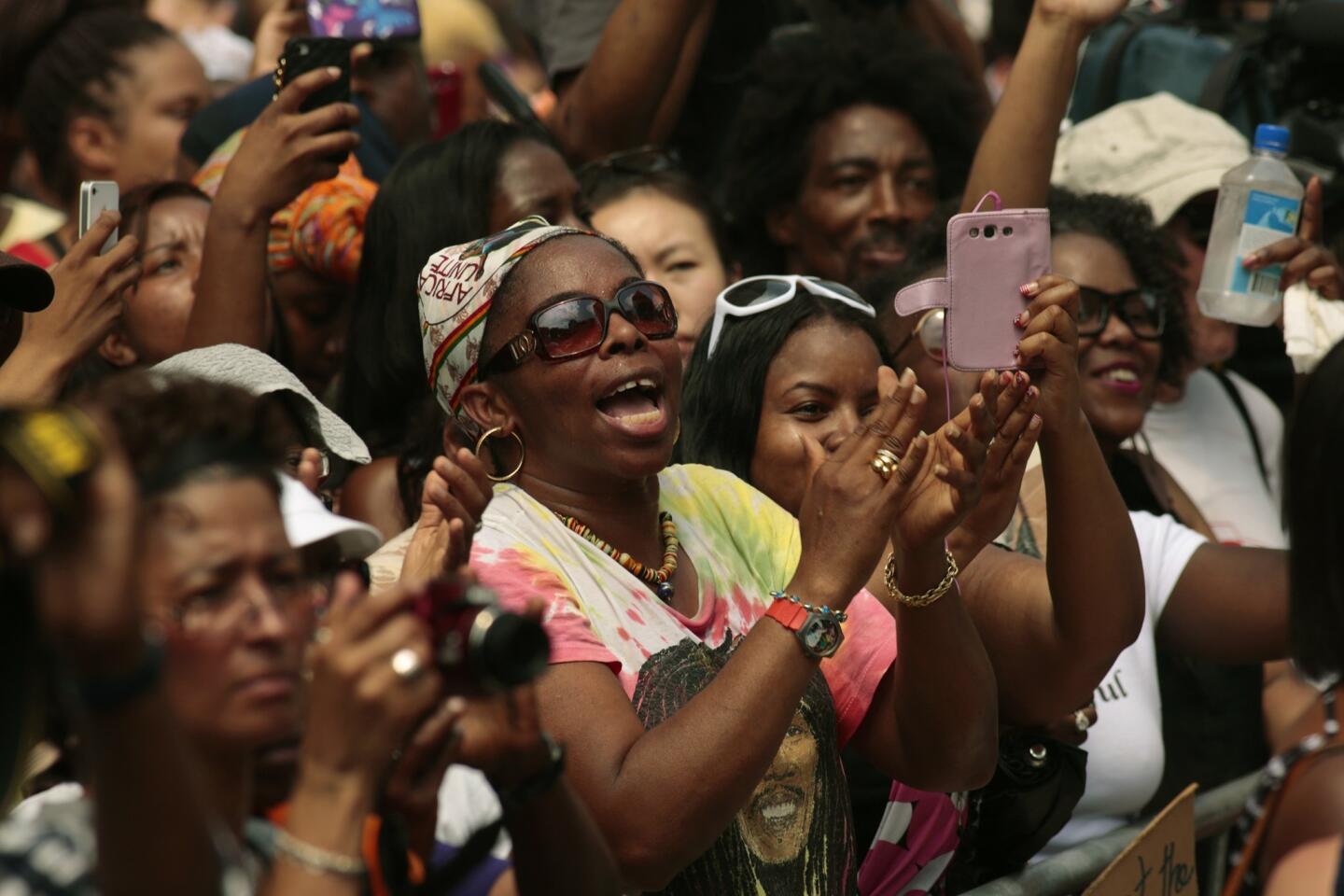

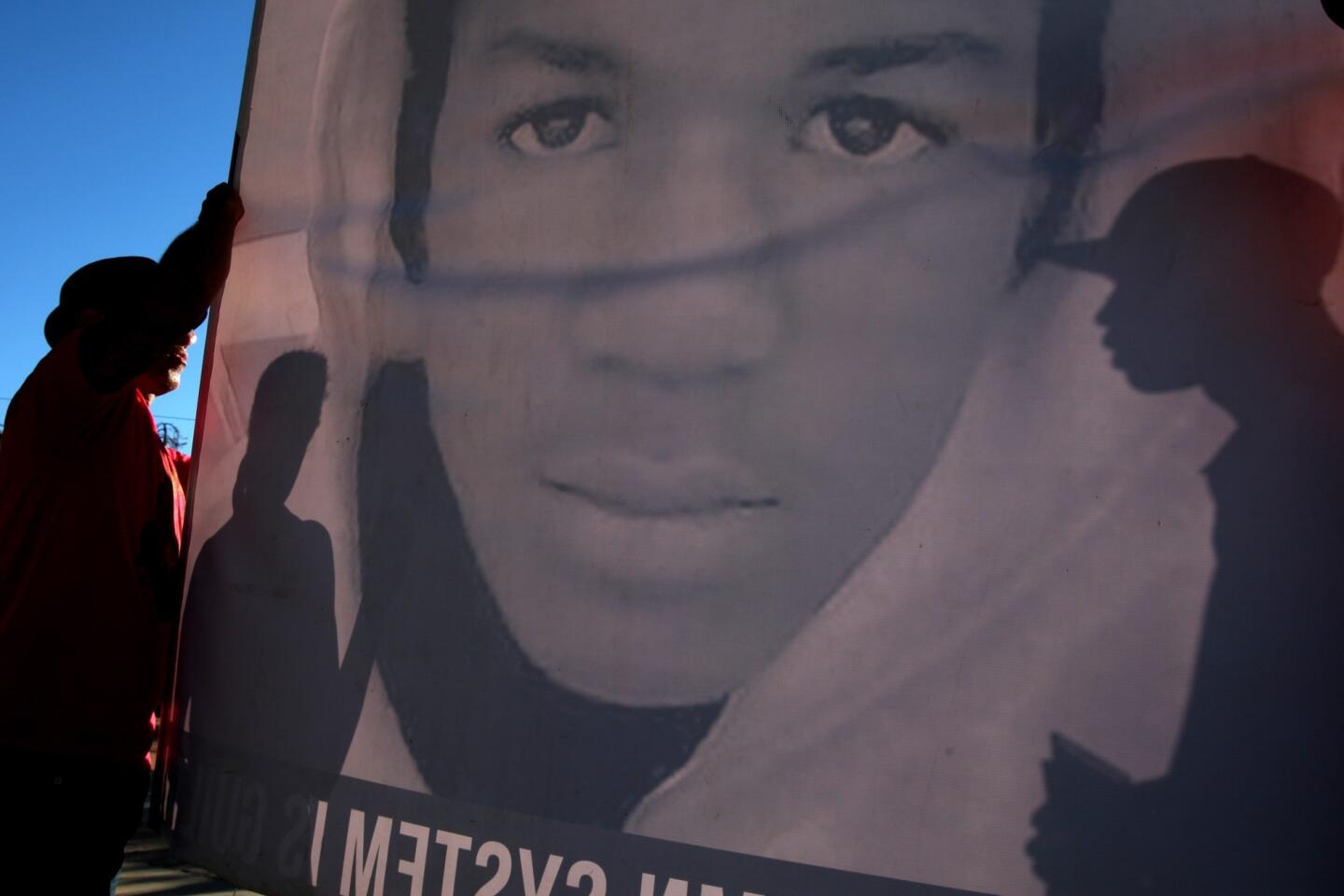

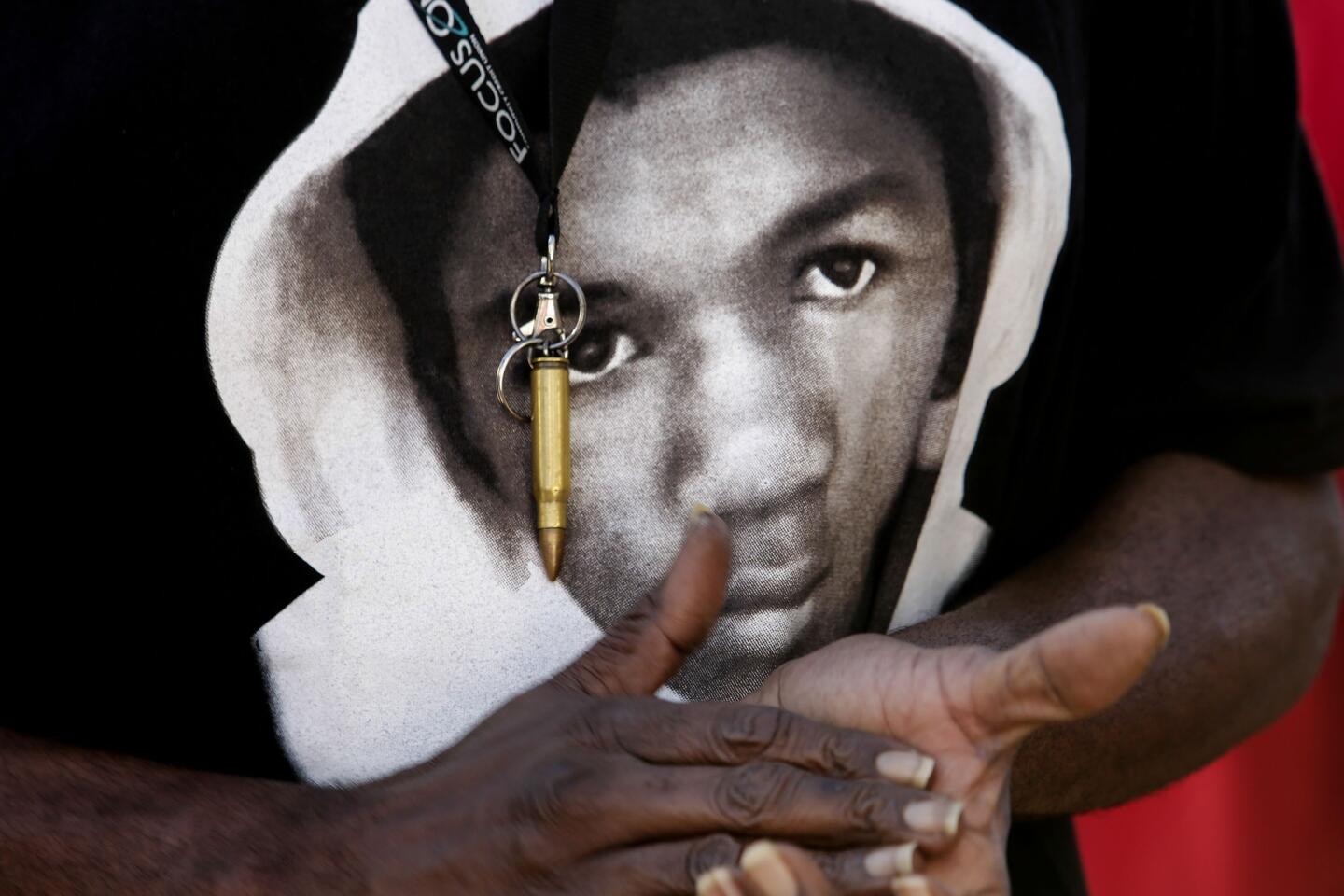

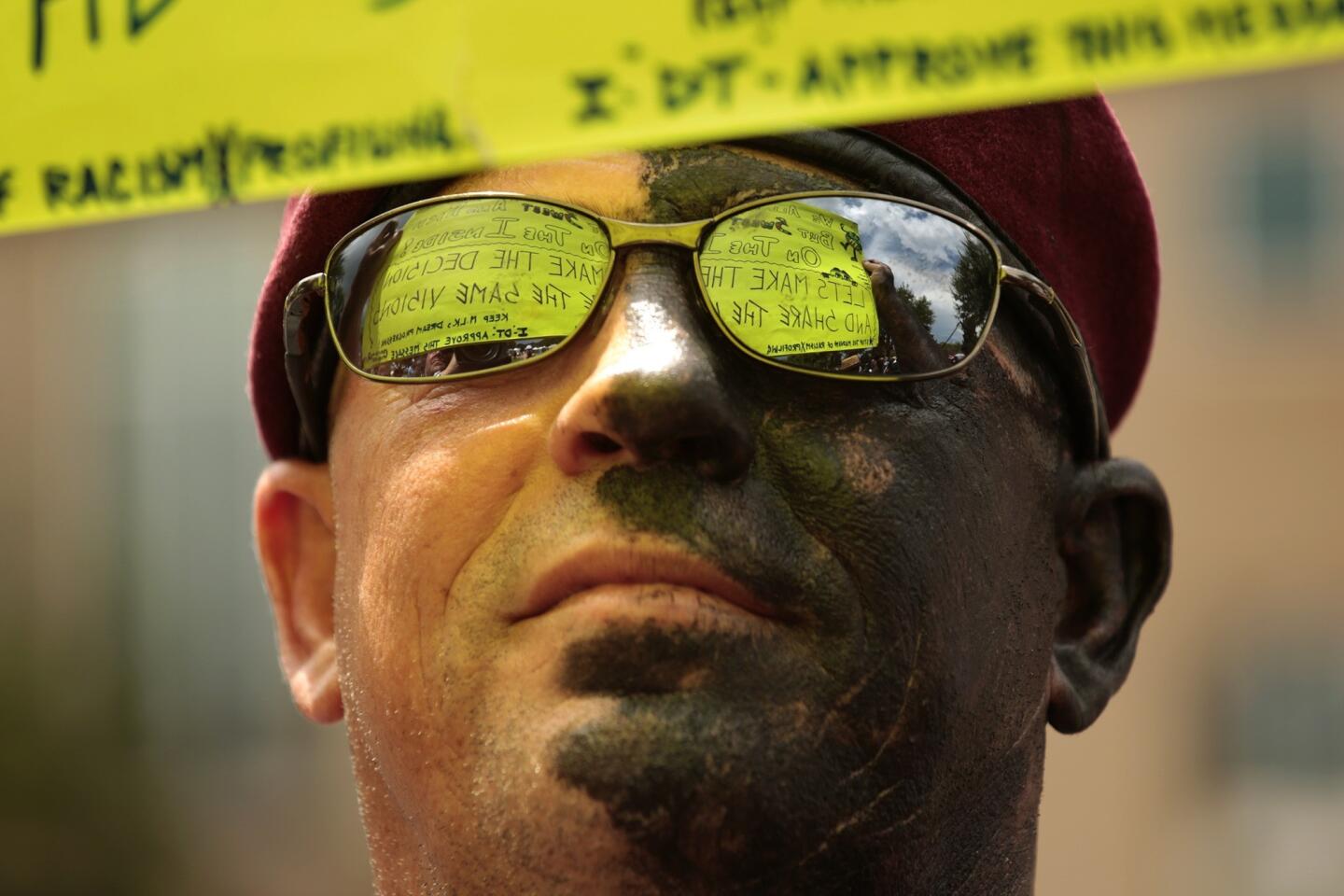

In the wake of the George Zimmerman verdict, which acquitted him in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, activists took to the streets across the nation to stand up for civil rights. For many, this was a black-and-white case. A neighborhood patrolman was spooked by a black 17-year-old wearing a hoodie. He shot and killed the unarmed teenager, claiming self-defense. And he got away with it.

Writing about the verdict, Gawker’s Cord Jefferson lamented: “For people of color, it’s a vivid reminder that we must always be deferential to white people, or face the very real chance of getting killed.”

The following day, a woman at a demonstration in New York also addressed the dichotomy that still exists in our country. Using the white skin on her back as a billboard, she asked, “Why do I not look suspicious? #stopracialprofiling.”

Activists are spreading an important message, but what will happen when the demonstrations stop? Will we forget about Trayvon Martin? That is Times reader Shawn Johnson’s fear. Excerpted from his thoughtful letter to the editor:

“I would love for us to realize that as a country, we are bigger than this and will learn and grow from this. I would love for us to realize that a person of color’s death impacts us all when it is done unjustly. I would love to believe that something good will come out of this.

But in the end, the cynic in me says that when the protesting stops, when the anger subsides, when the next big news story comes along, all that will be left is a grieving mother and a father trying to figure out why this happened.”

But we can’t let cynicism overwhelm us. If we want to honor Trayvon Martin, we have to use this moment as a catalyst for meaningful changes.

Commenting on America’s justice system, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes:

You should not be troubled that George Zimmerman “got away” with the killing of Trayvon Martin; you should be troubled that you live in a country that ensures that Trayvon Martin will happen. [...] When you have a society that takes at its founding the hatred and degradation of a people, when that society inscribes that degradation in its most hallowed document, and continues to inscribe hatred in its laws and policies, it is fantastic to believe that its citizens will derive no ill messaging.

It is painful to say this: Trayvon Martin is not a miscarriage of American justice, but American justice itself. This is not our system malfunctioning. It is our system working as intended.

So, what should activists do next? Here’s Andrew Cohen’s take:

What the verdict says, to the astonishment of tens of millions of us, is that you can go looking for trouble in Florida, with a gun and a great deal of racial bias, and you can find that trouble, and you can act upon that trouble in a way that leaves a young man dead, and none of it guarantees that you will be convicted of a crime. But this curious result says as much about Florida’s judicial and legislative sensibilities as it does about Zimmerman’s conduct that night. This verdict would not have occurred in every state. It might not even have occurred in any other state. But it occurred here, a tragic confluence that leaves a young man’s untimely death unrequited under state law. Don’t like it? Lobby to change Florida’s laws.

For Scott Lemieux, this is another reminder that we need to get serious about our gun laws:

The problem with the acquittal was not a racist and unreasonable jury, either. Rather, the acquittal of Zimmerman reflects something else equally serious and unsettling: the failure of the law in many states to keep up with the realities of America’s gun culture. In a society in which many African Americans are presumed to be criminals and large numbers of people carry concealed deadly weapons, some ways of defining self-defense (even if they do not entail a right to stand one’s ground) may no longer be workable. [...] Carrying a deadly weapon in public should carry unique responsibilities. In most cases someone with a gun should not be able to escape culpability if he initiates a conflict with someone unarmed and the other party ends up getting shot and killed. Under the current law in many states, people threatened by armed people have few good options, because fighting back might create a license to kill.

The New York Times editorial board concurs:

In the end, what is most frightening is that there are so many people with guns who are like George Zimmerman. Fear and racism may never be fully eliminated by legislative or judicial order, but neither should our laws allow and even facilitate their most deadly expression. Trayvon Martin was an unarmed boy walking home from the convenience store. If only Florida could give him back his life as easily as it is giving back George Zimmerman’s gun.

And, more specifically, our editorial board recommends that volunteer patrols not carry weapons as a matter of law:

This is a moment for neighborhood watch and other citizen crime-prevention groups to take stock. Most patrol volunteers are already cautioned by police not to follow or confront anyone. Both law enforcement and watch groups should go further and prohibit volunteers from carrying weapons in the course of patrolling. Some groups already do this, and various law enforcement agencies discourage weapons as well. For example, the Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department, in its guidelines for citizen patrols, specifically states that volunteers should never carry any kind of weapon.

Such restrictions won’t end all violence, much less racism. But they may help prevent some tragedies — and extract some progress from this sad case. It is important to remember, after all, that just because Zimmerman may go free does not mean he acted wisely.

ALSO:

Keeping healthcare on track

Get a clue, Asiana Airlines, and don’t sue

Zimmerman verdict: Readers on all sides find little to like

Follow Alexandra Le Tellier on Twitter @alexletellier

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.