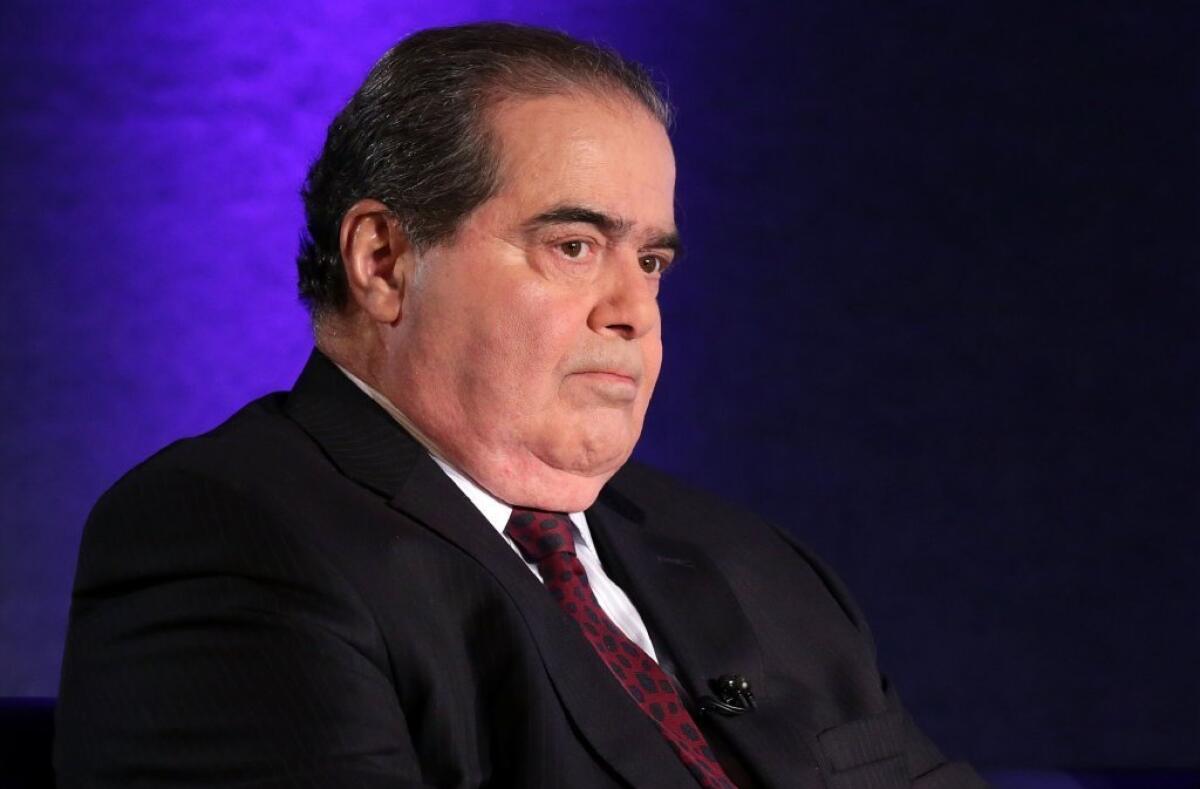

Opinion: No, Scalia’s comment about ‘less-advanced’ schools wasn’t racist

Justice Antonin Scalia wasn’t saying all blacks should attend inferior colleges.

Wednesday’s oral argument in the Supreme Court over affirmative action at the University of Texas had barely concluded before the Internet lit up with “shock horror” reactions to something Justice Antonin Scalia said.

Mother Jones reported Scalia’s comments under this headline: “Justice Scalia Suggests Blacks Belong at ‘Slower’ Colleges. Yes, he really said that.”

No, he didn’t, if that headline implies that Scalia believes all black students belong at “slower” colleges.

Let’s look at what Scalia actually said.

He was addressing Gregory Garre, a lawyer for the University of Texas, who was defending the university’s policy of counting race as one factor in a “holistic” review of applicants (which also includes factors such as extracurricular activities, socioeconomic background and “hardships overcome”).

“There are those who contend that it does not benefit African Americans to -- to get them into the University of Texas where they do not do well, as opposed to having them go to a less-advanced school, a less -- a slower-track school where they do well,” Scalia told Garre.

This is the “mismatch” theory, which holds that some minority students admitted to highly competitive universities fare worse there academically than they would have at less selective institutions. The argument is propounded in a book titled “Mismatch” by Richard H. Sander, a UCLA law professor, and the journalist Stuart Taylor Jr. (Their view is summarized here.) Sander also submitted a friend-of-the-court brief in the Texas case.

To put it mildly, the mismatch theory is controversial. In his excellent book “For Discrimination” (a defense of affirmative action), Harvard Law School professor Randall Kennedy approvingly cites academics who say that the theory underestimates the advantages minority applicants receive from attending highly competitive schools even if they earn lower grades than their classmates. (Michael Kinsley made the same point in a characteristically pithy op-ed column.)

What isn’t controversial – even among supporters of racial preferences – is that there would be fewer minority students at top-tier institutions if admissions programs didn’t treat race as what the Supreme Court has called a “plus” factor. In other words, black students often come to such campuses with lower SAT scores and grades than their white classmates.

In an op-ed column in the Wall Street Journal timed to coincide with Wednesday’s argument, Gregory Fenves, the president of the University of Texas at Austin, made the point explicitly: “Experience shows what will happen if the Supreme Court rules against us. Student diversity will plummet, especially among African Americans.”

The L.A. Times made the same point in our editorial urging the court to rule for the university: “For the foreseeable future, especially at highly competitive universities, meaningful racial diversity will require some consideration of race in the admissions process.”

Why? Because, for a host of reasons including a legacy of racial discrimination and unequal schools, many (not all) black and Latino applicants don’t have the same academic preparation as other, more privileged applicants to the most selective public and private universities.

Far from being racist, that proposition is an acknowledgment of racial inequality -- and it’s central to the argument for racial preferences. Those preferences wouldn’t be necessary if applicants from all racial and ethnic groups possessed exactly the same paper credentials.

It’s silly for advocates of affirmative action to dissemble about this. And it’s equally silly to suggest that Scalia was being racist when he clumsily invoked the mismatch theory.

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

MORE ON AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

Opinion: Texas’ college admissions policies give the well-to-do a leg up

Op-Ed: Supreme Court should avoid discouraging meaningful diversity in higher education

Op-Ed: A conservative quandary in affirmative action case Fisher vs. Texas

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.