Opinion: The 101-year evolution of John Muir’s legacy

Californians have long venerated John Muir as their environmentalist role model, a man whose campaigns and writings saved the Yosemite Valley and helped launch the national park system.

Vast stretches of California’s mountains and lush forests carry his name — the John Muir Trail, the John Muir Highway, the Muir Woods and the John Muir Wilderness, to name a few. His naturalist spirit continues to guide the actions of environmentalist organizations like Sierra Club —which Muir founded in 1892.

The Times’ coverage of Muir’s death — 101 years ago to the day — stitched this illustrious legacy into history.

Los Angeles Times

“John Muir was one of the most remarkable characters of all the remarkable men and women produced by contact with the primitive West,” his obituary, which filled nearly a full page, read in the paper on Dec. 25, 1914.

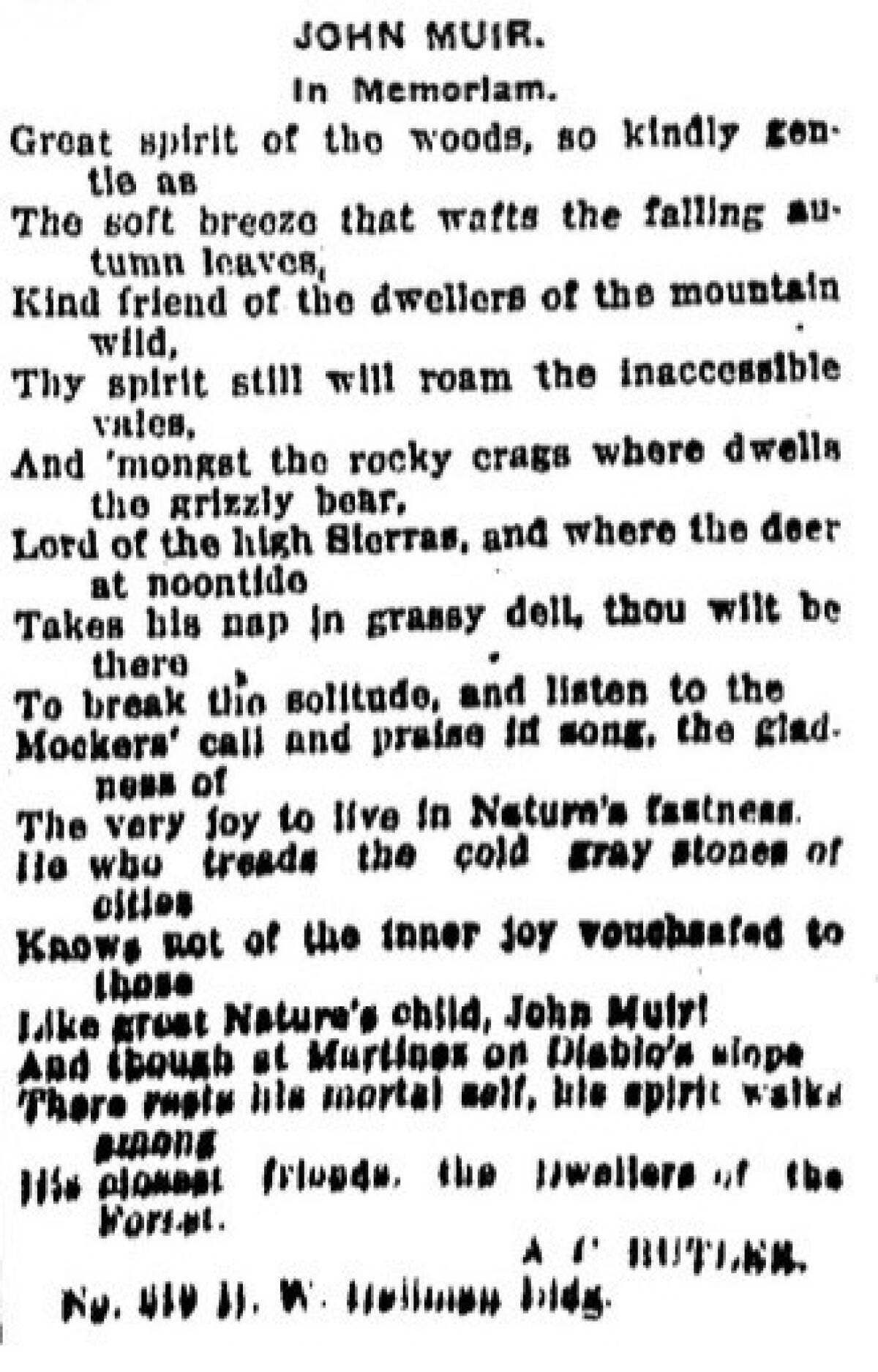

Weeks later, on Jan. 10, an “In Memoriam” poem for Muir held him in almost biblical esteem, giving him titles like “Lord of the high Sierras” and “great Nature’s child.”

Los Angeles Times

But, more recently, Times articles surrounding Muir’s legacy have explored a more critical approach. A 2014 article on the centennial of his death denoted Muir the “patron saint of environmentalism,” but worried that Muir’s privileged white perspective and alleged prejudice toward Native Americans holds the environmental movement back.

This criticism was met with fierce backlash from Times readers. A wave of letters defending Muir made it clear that Californians weren’t ready to see their bearded Scottish American role model as anything less than a hero. Indeed, when you look out at the glacier-carved serenity of Yosemite National Park, it’s almost impossible not to put Muir on a pedestal. We have Muir to thank, after all, that such a quiet and rugged space still exists in this state at all.

Today, on the 101st anniversary of Muir’s death, Daniel Duane writes another piece trying to reconcile how we square the stunning legacy Muir helped protect with the way Yosemite’s land was yanked from its original residents.

Undoubtedly, we should appreciate Muir’s tireless work to protect California’s landscape and wildlife. But all heroes are flawed. There's nothing wrong with making honest, but respectful, reassessments of the heroes of the past as we age and mature.

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.