Opinion: Unhappy anniversary, Citizens United

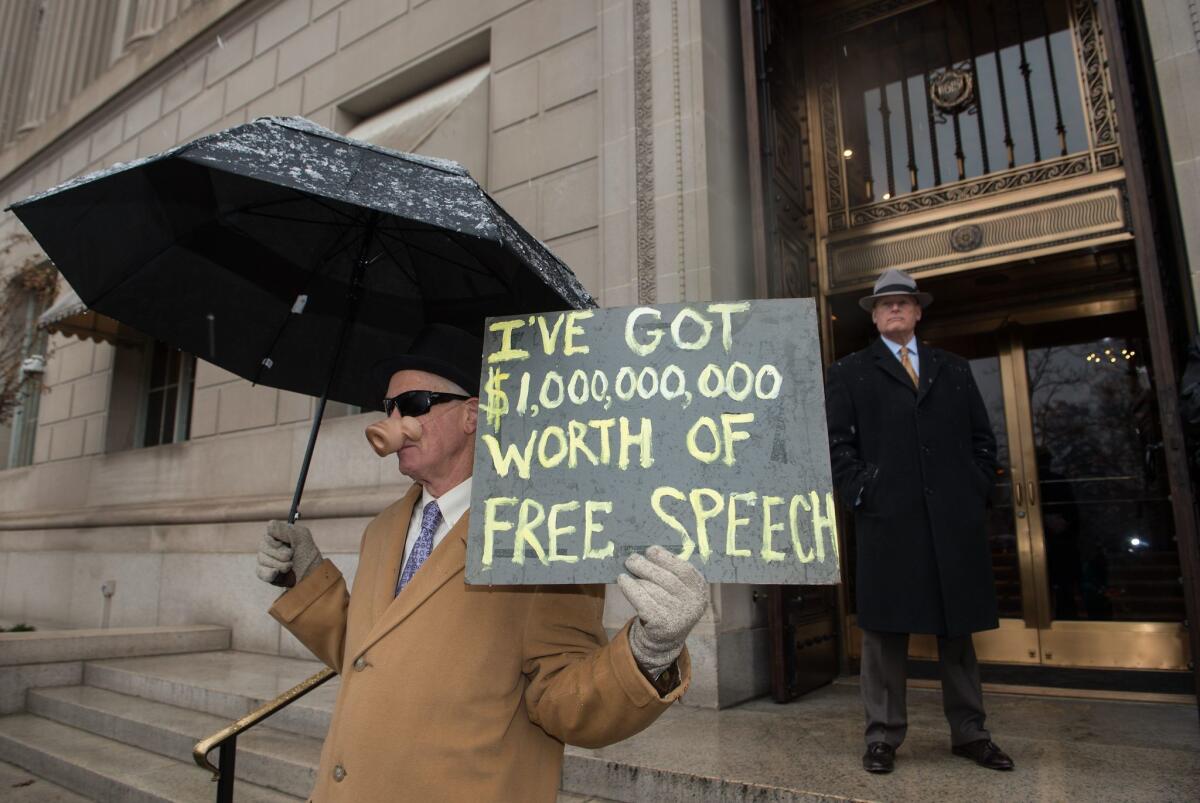

Wednesday was the fifth anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission, and in case the justices weren’t aware of the fact, some Code Pink-style protesters reminded them.

Scotusblog picks up the story: “Just after the justices had taken the bench at 10 a.m., and as they were about to announce opinions, a woman stood from her seat near the back of the courtroom and said, ‘I rise on behalf of democracy.’ She continued with a mention of Citizens United, the 2010 ruling that removed limits on independent political expenditures by corporations and unions. Three Supreme Court police officers quickly converged on her.”

President Obama observed the anniversary more decorously, issuing a statement saying, in part: “Our democracy works best when everyone’s voice is heard, and no one’s voice is drowned out. But five years ago, a Supreme Court ruling allowed big companies – including foreign corporations – to spend unlimited amounts of money to influence our elections. The Citizens United decision was wrong, and it has caused real harm to our democracy. With each new campaign season, this dark money floods our airwaves with more and more political ads that pull our politics into the gutter.”

So are the protester and the president right? Is Jan. 21, 2010, a day that should live in infamy?

Not exactly. As the Los Angeles Times observed at the time, Citizens United was wrongly decided. And it has had undesirable consequences, though not precisely the ones its critics predicted.

First, the decision went too far. The court could have resolved the issue before it – whether the Federal Election Commission could restrict a conservative group’s video-on-demand mockumentary about Hillary Rodham Clinton – without ruling that corporations had a right to air any and all “electioneering communications” close to an election.

There were real problems of overbreadth with that provision of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, which presumed that any broadcast mentioning a candidate was a campaign ad. In 2007 the court had narrowed the scope of the prohibition by limiting it to messages that, as Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. put it, are “susceptible of no reasonable interpretation other than as an appeal to vote for or against a specific candidate.” The court could have used Citizens United to delineate the definition further, or it could have concluded that a video-on-demand film wasn’t covered by the law. Instead it overturned all limits on corporate “electioneering communications.”

Citizens United inspired a lower-court decision that encouraged wealthy individuals to contribute to independent political action committees. And it did allow corporate money to flow into election-related advertising, though much less than critics of the decision expected. (Many companies seem to have realized that spending on political campaigns might alienate shareholders and customers.)

But a lot of what you’ve heard about Citizens United is wrong. The decision didn’t allow corporations to donate directly to political campaigns. It didn’t give rich individuals the right to spend unlimited amounts of their money on independent political ads; they already enjoyed that right under a 1976 Supreme Court decision called Buckley vs. Valeo. And, contrary to what Obama said, Citizens United didn’t greenlight spending by foreign corporations on U.S. elections. (Obama has told this fib before.)

Nor, despite what some critics of Citizens United believe, is overruling Citizens United the only way to deal with problems posed by “dark money,” a reference to funds spent on politics by tax-exempt “social welfare” groups that can conceal the identities of their donors. Congress and/or the Internal Revenue Service can force the names of those donors into the sunlight.

Congress can also do a lot to unmask the donors behind “political ads that pull our politics into the gutter” by enacting a perennial proposal called the Disclose Act. Finally, Congress and the Federal Election Commission can and should clamp down on covert coordination between “independent” political committees and candidates’ campaigns.

These proposals admittedly have less sex appeal than the idea of amending the Constitution to overrule Citizens United and Buckley vs. Valeo. But they would make a difference.

Of course, a constitutional amendment would make more of a difference. But it’s a bad idea. As the Supreme Court said in Buckley, “the concept that government may restrict the speech of some elements of our society in order to enhance the relative voice of others is wholly foreign to the 1st Amendment.” Such an amendment could also undermine freedom of the press, given that most newspapers are published by corporations.

Besides, the Constitution isn’t going to be amended to overrule Citizens United -- any more than it was amended after a public outcry about another unpopular 1st Amendment decision, the 1989 ruling striking down laws against burning the American flag. For good reasons, it is extremely difficult to amend the Constitution.

Those who bewail the influence of “dark money” and the proliferation of “gutter” politics should set their sights on achievable reforms: fuller and timelier disclosure, an end to the charade of “social welfare” groups spending money on election advocacy, and tougher measures to ensure that independent groups really are independent. They can still denounce Citizens United every Jan. 21st.

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.