Opinion: John Boehner resigns, a relic from a bygone era of deal-making

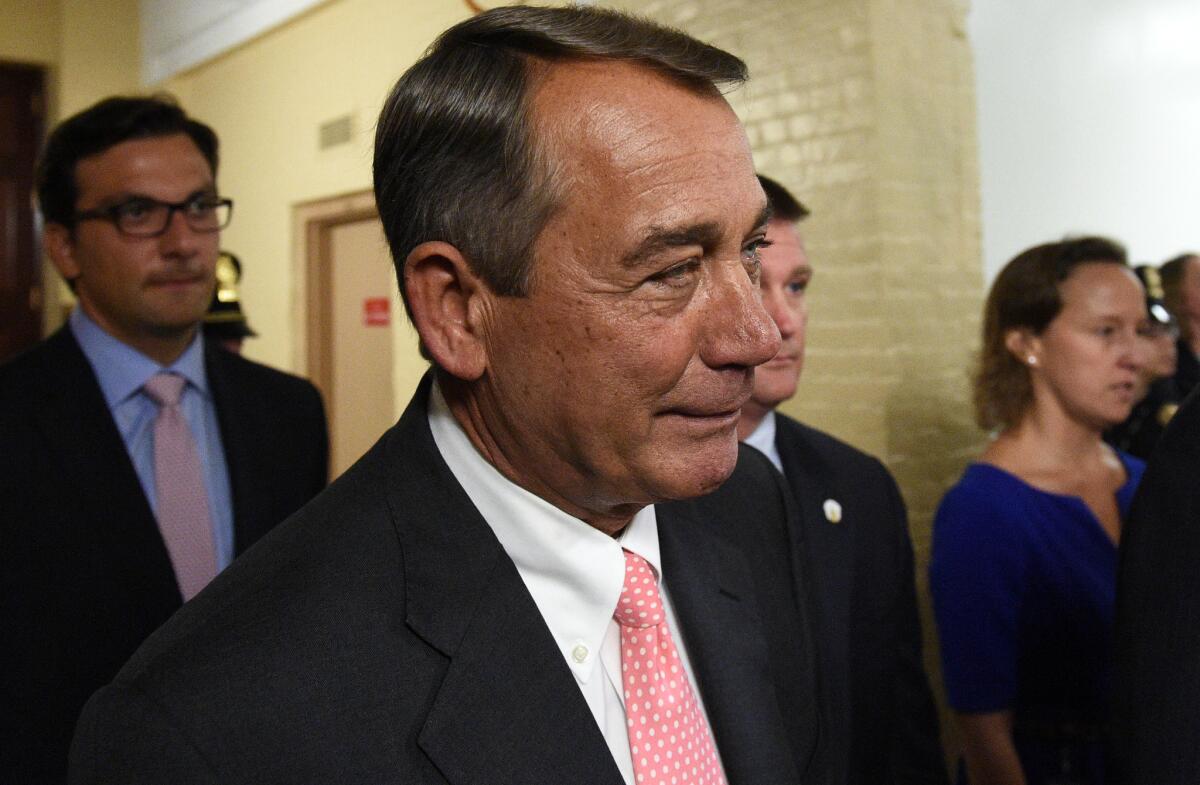

House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) leaves after announcing his resignation on Capitol Hill on Friday in Washington, D.C.

What is the speaker of the House? A traffic cop? A bridge builder? A dictator?

One reason John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) resigned Friday, in the midst of his third Congress as speaker, was that the people he was leading couldn’t agree on an answer. Or maybe more to the point, he couldn’t make them accept his.

Boehner, a bartender’s son representing a conservative southern Ohio district, was by all accounts a dealmaker -- the kind of leader who saw how to reach a compromise that could keep things moving forward. But a large chunk of the House GOP rank and file wasn’t interested in compromising, at least not in the win-win sense. They wanted to use the power of the majority to extract as much as they could from Democrats and the White House. In their view, brinkmanship wasn’t a sign of dysfunction, it was a tool that needed to be used.

For tea party-affiliated Republicans, Boehner’s predecessor -- Democrat Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco -- and the Senate majority leader for the first four years of Boehner’s tenure -- Harry Reid of Nevada -- were instructive models. Pelosi may not have enjoyed the unwavering support of her entire caucus, but she pushed big, divisive bills through the House over the opposition of virtually every Republican. And after Republicans took the House, Reid killed House bill after House bill, including many that had bipartisan support even in the Senate, in an attempt to shield vulnerable Senate Democrats from politically tough votes or President Obama from having to make a controversial veto.

Never mind that these strategies didn’t stop Republicans from taking control of Pelosi and Reid’s chambers -- in fact, they probably contributed to some Democrats’ defeats. Their actions showed that the leader of the chamber has real power, and some Republicans grew increasingly frustrated at Boehner’s unwillingness to use it.

That’s not to absolve Boehner of any fault. He seemed to be a man out of time, someone who would have excelled as speaker in less polarized days -- for example, after the GOP took over the House in 1995. Those Republicans had bouts of chaos too, but they settled pretty quickly into a working relationship with President Clinton that yielded some real achievements, including welfare reform and a balanced budget.

It’s worth remembering that many House Republicans then were self-styled political and civic revolutionaries intent on changing government fundamentally, much like the tea party-affiliated members today. Yet the current group has clung much longer to the notion that take-no-prisoners is a viable method of governing, unwilling to acknowledge that there’s little gained from having a bill die by filibuster or veto. We’re already so polarized as an electorate that the voters who dislike Obama won’t dislike him any more after he vetoes a bill defunding Planned Parenthood than they did before.

Boehner might have tried to be more of a whip-cracker, the sort of punitive speaker who exiles members to sub-basement offices and third-tier committees when they don’t abide by his dictums. Perhaps then we could have seen how much more Congress could have accomplished had Boehner been allowed to try advancing the conservative agenda through dealmaking rather than empty threats and suicidal charges from the trenches.

He did a little bit of whip-cracking, actually. But it didn’t bring the restive “Freedom Caucus” into line, either because no one could have or because Boehner had no credibility as a bully. Regardless, his last act appears to have spared the House the embarrassment of another futile government shutdown, at least for a few months. Then we’ll see whether a new ringleader can tame the circus.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.