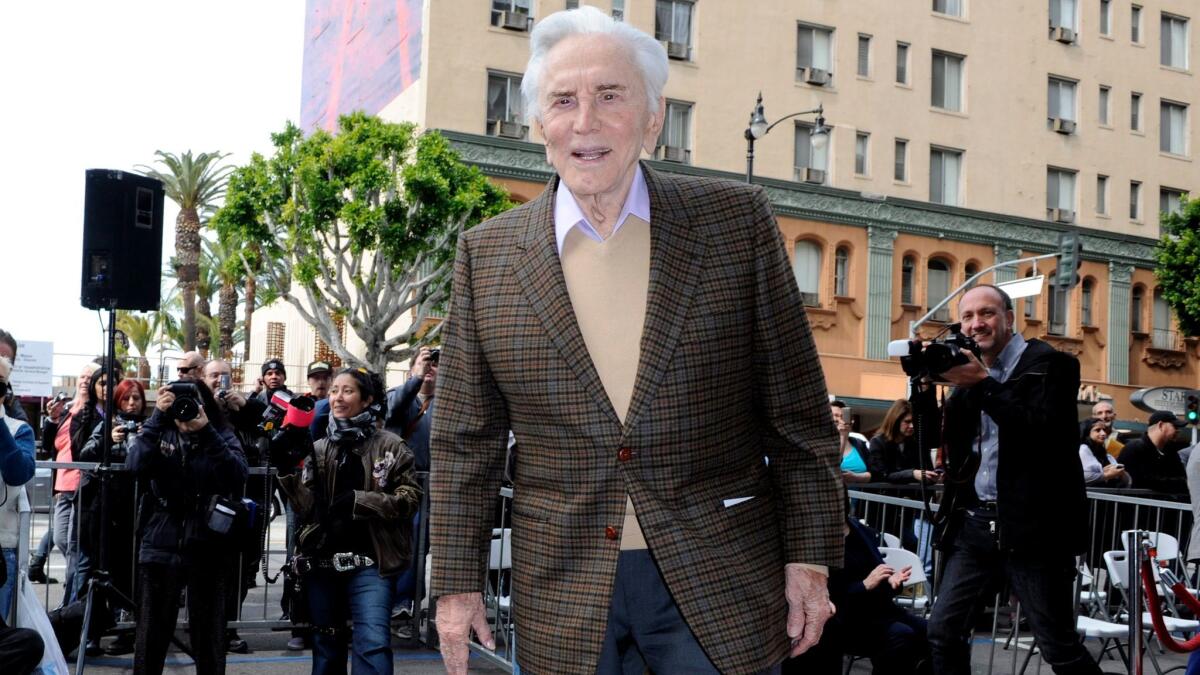

Op-Ed: Sharing biblical stories and 100 years of life lessons with Kirk Douglas

We were in the middle of the Book of Esther, where the new queen is being prepared by the eunuchs of the court for a fateful meeting with the king. “I’ve got the movie,” Kirk Douglas said, eyes sparkling as he imagined a scene playing out.

“What’s the movie?” I asked.

“Well, I play one the of the court eunuchs,” he said. “I dress her and undress her. Only I’m not really a eunuch!”

For the last 20 years I have studied Bible once a week with Douglas. In those years he lost his youngest son to a drug overdose, endured the heartbreak of seeing his grandson imprisoned for dealing drugs, watched his son Michael win a lifetime achievement award (“What does that make me? Winner of some posthumous prize?”), marked 50 years with his wife, Anne, and struggled with his legacy and mortality. On Friday he turned 100.

Several years ago I asked why he was studying the Bible at this stage of his life. It is the best book of stories in the world, he replied.

It is difficult to imagine what it means to live a century, world-famous for most of it. His relatively modest Beverly Hills house is filled with gifts from other world-famous people. I admired an ornate hand mirror on my first visit. “Oh, Anwar Sadat gave that to me,” he said, offhandedly. Once you’ve partied with Frank Sinatra and John F. Kennedy, you aren’t easily excited.

I asked him once if he remembered Jackie Robinson. “Do I remember him? Do I remember him?” he scoffed. “Rabbi, I was 4 years old when women got the vote.” When on a hot day I said how much I appreciated air conditioning and guessed that as a kid he’d probably relied on a block of ice and a fan, he fixed me with a half-comic glare and said, “Who had a fan?”

Douglas was a notoriously pugnacious star who projected a burning, internal anger on the screen. I still see glimpses of that smoldering ire as he reads certain sections of the Bible or discusses political events when we meet; it was not entirely acting. A doctor who treated many Hollywood stars confided to me that Douglas was among his toughest patients. “He once punched a hole in my wall because he had a cold,” he told me. “As if germs had some nerve inconveniencing Kirk Douglas.” He could also be openhanded and brave on behalf of the underdog. His orneriness was part of what enabled him to insist that blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo get sole screen credit for “Spartacus” in 1960.

Those sharp edges have softened over time. “I don’t know if studying made him nicer or he was nicer so he studied,” his son Michael told me several years ago. “But you are seeing him at his kindest.”

Several years ago he and Anne sold much of their precious art collection to fund a foundation that has built more than 400 school playgrounds all over California. They have attended, together, the opening of every single one. They have given away tens of millions, notably to schools and the Motion Picture Home for the Aged.

Douglas has survived a heart attack, a stroke and a helicopter crash. He reads the Bible for its stories of struggle, and feels an affinity for the more troubled characters. When my book on King David was optioned by Warner Bros., he lamented being too old to play him in the movie. David, he told me, was his kind of complicated character, noble, strong and sinful. Douglas often recounts something a rabbi told him when he first began to study Judaism: that he loved being Jewish because it was so dramatic.

Facing his mortality, Douglas told me about sitting with his mother at the end of her life some 75 years ago. She held his hand and told him not to be afraid, that everyone dies. He had an extremely contentious relationship with his father, but he adored his mother and she adored him. “When my boy walks,” he remembers her telling her friends, “the earth trembles.”

Now when he walks, he trembles. He complains, but mostly with amazement that he is 100.

Several years ago I asked why he was studying the Bible at this stage of his life. It is the best book of stories in the world, he replied, then added, “At this point it is all about God, people and charity, and I have my doubts about God, but none about charity and people.”

Studying Judaism for years has softened him, but not dampened his drive to know more, and do more. It has turned him outward to the world. That same day as I was leaving he walked me to the door and said, “Come back soon. The sun is setting and there is still a lot to learn.”

Rabbi David Wolpe is the senior rabbi at Sinai Temple and the author of eight books, including “David: The Divided Heart,” which is being developed into a movie.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.