Op-Ed: Jonestown victims drew public scorn, but now we know the story of their betrayal

Forty years ago, an American preacher and madman named Jim Jones orchestrated the largest mass murder in recorded history when he forced more than 900 men, women and children to drink a cyanide-laced punch at his eponymous settlement in Guyana.

Early news reports referred to Jonestown as a “cult of death” and spread the idea that residents calmly lined up on Nov. 18, 1978, to offer cups of poison to their children before drinking it themselves. Reporters lustily relayed what sensational details they had, but also filled in the gaps with outrageous claims. “They welcomed their own destruction,” declared one San Francisco newscaster. That became the “official” take on the tragedy: A bunch of Californian lunatics had killed themselves at the behest of a sick demagogue.

This caricature of the Jonestown victims was much easier to digest – and dismiss – than the true story, which was one of betrayed ideals, terrifying helplessness and unfathomable heartbreak.

Even as the news media prompted public scorn for Jones’ victims, their bodies lay in the searing equatorial sun for four days while the United States and Guyana squabbled over what to do with them. The U.S. pressured Guyana to bulldoze the dead into a mass grave — but Guyana refused to clean up what it saw as an American mess. By the time U.S. soldiers bagged the bodies and flew them to Dover Air Force base in Delaware, they were so badly decomposed that forensic examiners could identify only 69% of the victims. Of these, roughly half were buried by their relatives; other families were so ashamed of their link to the “suicidal cult” that they refused to accept the remains of their loved ones. Several cemeteries refused to accept the remaining 409 bodies because of the stigma of Jonestown — and vociferous objections from neighbors — before Evergreen Cemetery in East Oakland agreed to bury them.

Jones’ victims dreamed of a better, more equitable world — a dream many of us share today.

Surviving members of Jones’ church, Peoples Temple, were also vilified. Angry crowds gathered outside the building on Geary Boulevard in San Francisco, shouting, “Baby killers!” Those returning from Guyana – penniless and distraught – were turned away from welfare and food stamp offices; employers wanted nothing to do with them. They were deemed monsters, deserving of their fate.

Today, the horrific mass murder at Jonestown has been reduced to a banality. “Don’t Drink the Kool-Aid” is a glib warning against groupthink or blind loyalty to a charismatic leader or institution. (For the record, it wasn’t poisoned Kool-Aid served on that long-ago night, it was poisoned Flavor Aid.)

In recent years, the pervading view of Jonestown has begun to change. A number of survivors have published first-person accounts about their experiences in the jungle community. And a lawsuit compelled the FBI to release some 50,000 pages of documents and nearly 1,000 audiotapes collected from Jonestown after the massacre. Collectively, this new information deepens our understanding of the tragedy and starkly contradicts the narrative of blame imposed on Jones’ victims.

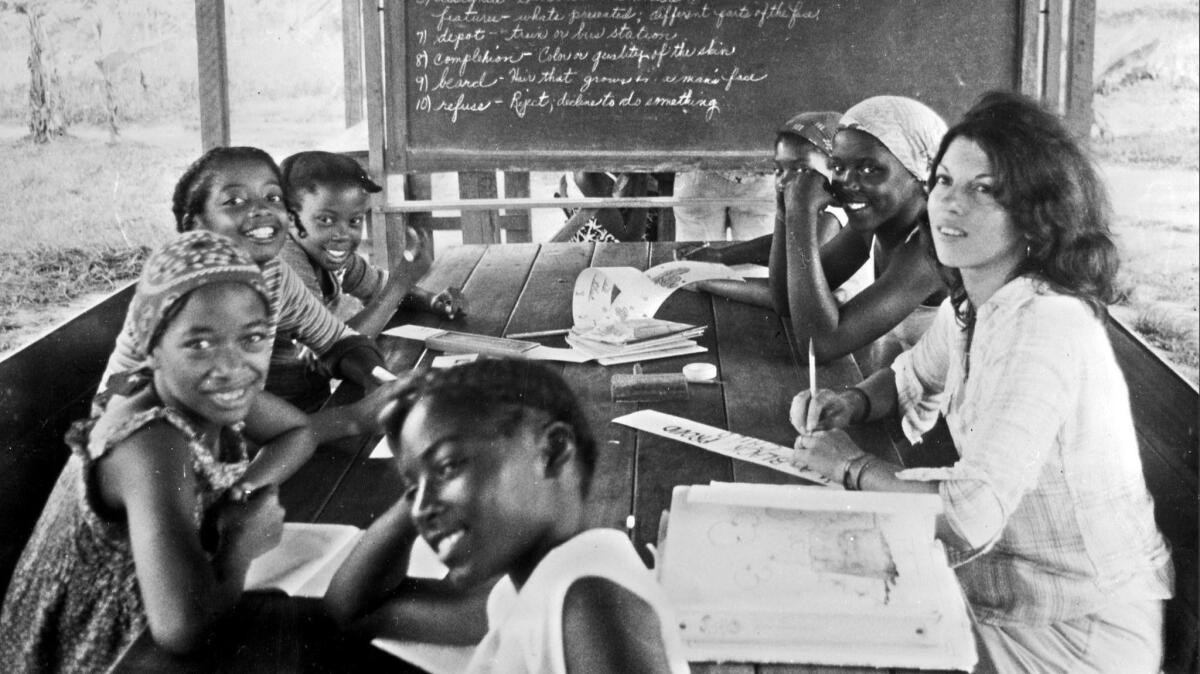

Jones sold his town to his followers — most of whom were African American — as a utopia where they could live free of America’s racism, sexism and elitism. Instead, the nearly 1,000 Americans who participated in this bold social experiment over a four-year period found themselves trapped in a dystopian nightmare. Residents believed they could return home at any time if Jonestown wasn’t to their liking. But it was a two-day river journey from the capital of Georgetown to Port Kaituma, the closest village to Jonestown. No roads connected the capital to the hinterlands — still the case today. Jones confiscated everyone’s passports and money and told them that if they didn’t like it, they could “swim home.” Despite promising families that they would live together in private homes, he separated husbands and wives, parents and children. Despite boasts of bumper crops, the thin jungle soil couldn’t produce enough food to feed the increasingly hungry residents.

But the most chilling aspect for immigrating Temple members was the change in their leader. After sequestering his followers in the jungle, Jones dropped the façade of caring pastor and became a vulgar, drug-addled tyrant who banned any criticism of his town. Even mentioning the heat was considered “counter-revolutionary.” He forbade residents from leaving the isolated settlement, telling them the wilderness that surrounded them was infested with poisonous snakes, big cats and shadowy mercenaries who wanted to destroy their community. He censored incoming and outgoing mail to make the world believe Jonestown was a happy success.

It was in Guyana that Jones first held a vote on his idea of “revolutionary suicide.” Although he’d discussed the notion in California with his inner circle — an equally nihilistic coterie that ultimately helped him bring his macabre plan to fruition — the regular members of Peoples Temple moved to Jonestown seeking a better life for themselves and their children. When he brought up the prospect at an assembly in September 1977, residents were stunned and objected vociferously. They hadn’t come to the promised land to die – they came to thrive. But night after night, he ground them down, refusing to let anyone go to bed until everyone raised their hands in ostensible support of their own deaths. According to one survivor, the constant talk of “revolutionary suicide” became boring and people raised their hands just so they could go sleep.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

On Nov. 18, 1978, a deadly chain of events was set in motion. Congressman Leo Ryan (D-San Mateo) — who’d flown down to investigate claims that residents were being held against their will — was leaving Jonestown with a group of unhappy residents when they were ambushed by Jones’ henchmen. The congressman, three reporters and a fleeing resident were killed. Before the news of Jonestown’s failure became public, Jones ordered the death of his people. Surrounded by armed guards, residents were given a choice: They could die by bullet or they could die by poison. Life was never an option.

Jones recorded the event for posterity, in what’s known as the “Death Tape.” It’s a harrowing, heart-rending listen, easily found online. Jones stopped and started the recording more than 30 times, editing out protestations. His final sentence is a grotesque lie: “We didn’t commit suicide, we committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world.” The screams in the background tell the real story.

Jones’ victims dreamed of a better, more equitable world — a dream many of us share today. But instead of being remembered for their ideals, they are derided as freaks. These people who harbored such hope – and were so cruelly betrayed – deserve better.

It wasn’t until 2011 – 32 years after they were murdered – that Jones’ victims were finally honored with a plaque listing their names at the mass grave in Evergreen Cemetery. It’s a small step toward restoring their humanity.

Julia Scheeres is the author of “A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Jonestown.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.