Op-Ed: 50 years ago, Cesar Chavez led a crusade to unite and empower farmworkers

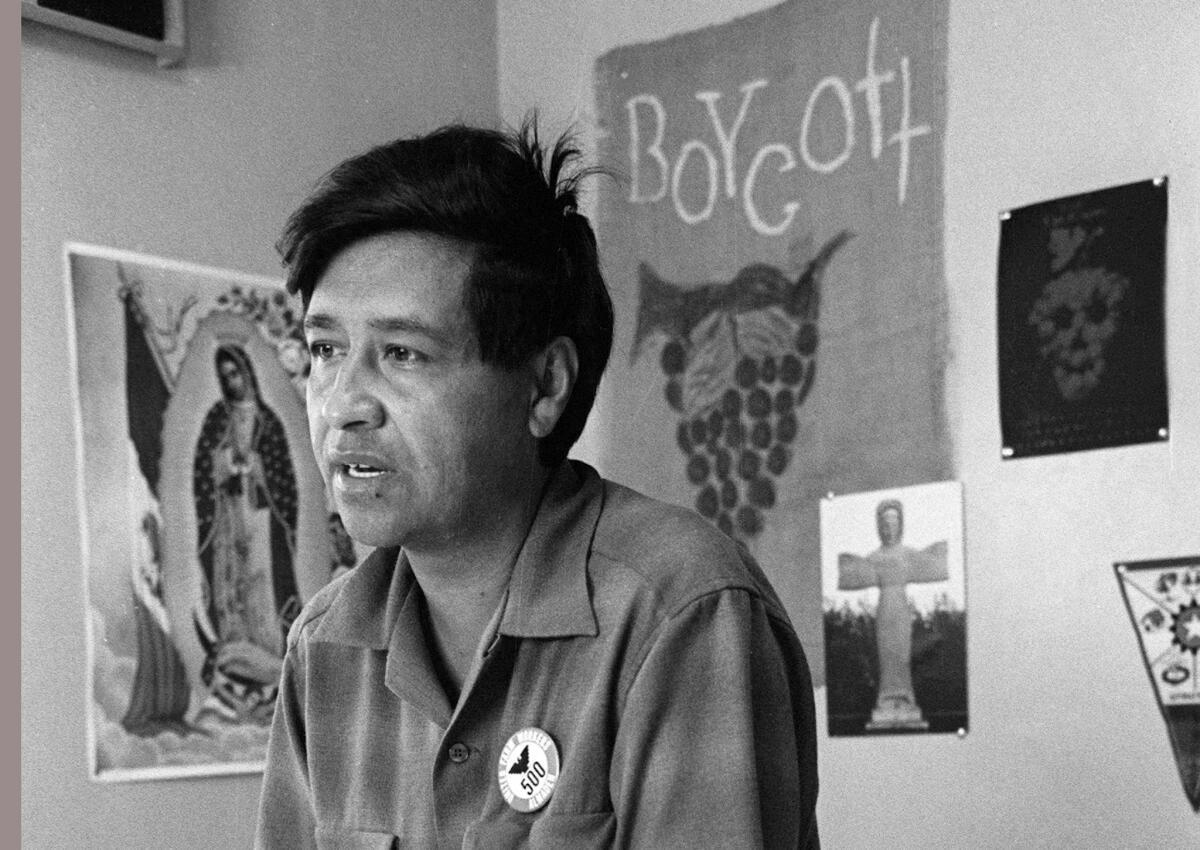

Cesar Chavez, farm worker, labor organizer and leader of the California grape strike, works in a Calif. office in 1965.

On a Thursday night 50 years ago, at the height of the table grape harvest in California’s Central Valley, hundreds of Mexican American farmworkers crowded expectantly into a Delano church hall. Most had worked their usual shifts in the vineyards, and many had stopped off after work at celebrations to mark Mexican Independence Day. The overflow crowd spilled into the church yard, excited and scared, angry and brave.

They were tired of being treated like disposable farm tools. Tired of being cheated out of even their meager wages. Tired of watching their mothers and sisters humiliated and harassed. Tired of being stripped of dignity. Tired of being invisible.

Many had never met the man who rose to speak, who would throw the spark that ignited fires that would turn la causa into front-page news. He, too, was still largely invisible. Short, dark-skinned, not physically prepossessing or particularly well spoken. He looked like one of them. That was part of his power.

Cesar Chavez knew even then that he was making history Sept. 16, 1965, as he called on members of the National Farm Workers Assn. to take a strike vote. He saved his notes. Later he would save much more, even tape recordings to preserve history verbatim. The notes for his talk at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church are a road map to the uprising that followed, laying out the moral code he would use to lead a movement: unity, religion, revolution, patience and sacrifice.

Chavez did not start the 1965 grape strike. On Sept. 8, Filipino members of a different union, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, had walked out of the vineyards, demanding an increase in pay to $1.40 an hour from $1.25. Filipinos were the packers and Mexicans were the pickers. Growers, who had long pitted one ethnic group against another, began to replace the striking Filipinos with Mexicans — despite qualms they might not be skilled enough to pack grapes.

Unless Mexicans honored the AWOC picket lines, the strike would collapse. Chavez knew he had no choice. “We must take risks if we are going to move forward,” he had written to a colleague in the early days of building his union. He selected the date and place of the strike-vote meeting with care. When David takes on Goliath, every little advantage helps. Mexican Independence Day celebrations emboldened workers, and Chavez capitalized on the symbolism, comparing farmworkers’ struggles to that of the Mexicans who revolted against Spanish rulers.

Father Hidalgo launched the Mexican Revolution on Sept. 16, 1810, Chavez reminded the workers, a holy crusade. The priest attached a portrait of Our Lady of Guadalupe to his lance as he headed into battle, just as Chavez would lead marches behind the banner of the patron saint of Mexicans. Hidalgo was martyred for the cause, Chavez recounted. But the cause lived on. We will conquer the growers just as the Mexicans conquered those who enslaved them, he told the workers. It was fitting to begin “our crusade” in a church.

Chavez understood the struggle would be long and hard, not only against the growers. He had spent the last three years going town to town in the San Joaquin Valley, talking to workers, trying to persuade them to join his organization, trying to build a union strong enough to strike. He thinned beets when dues didn’t pay the rent, watched his kids suffer malnutrition and sometimes fought off his own “gut tearing fear.” His challenge was to instill hope in workers who believed they had no power — enough hope to overcome fear.

“I start out by telling them this is a movement (un movimiento) and that we are trying to find the solution to the problem,” he wrote to his mentor, describing how he organized in small groups. “I tell them I’m looking for the true workers who depend 100% on farm work to make a living.... I say that this worker is not recognized because he is white, brown or black but is recognized because his back aches with the torture of farm work and his shoulders are stooped with the weight of injustice.”

The idea of uniting workers of different races was in itself revolutionary, and the leaders of both unions recognized its importance. Mexicans and Filipinos would have to overcome the distrust that had been deliberately sowed for years.

Above all, Chavez valued sacrifice. He told the workers they would need to sacrifice, and they did. They gave up jobs, homes, cars. They faced brothers and cousins across picket lines. They ate at communal kitchens, took care of one another’s kids, set up a makeshift clinic.

They did things they had never dreamed they could do. They walked 300 miles along Highway 99 on a pilgrimage to Sacramento. Blocked buses that tried to bring scabs into the fields. Moved to cities across the country where they knew no one to stand in parking lots asking consumers to boycott grapes.

The two unions formed the United Farm Workers of America, and the strike that grew from the vote in that Delano church lasted five years. Thousands were swept up by the crusade, and their lives were never the same. Chavez went from anonymity to the cover of Time magazine in a scant four years. The UFW negotiated dozens of contracts and gained tens of thousands of members — and then stopped organizing and lost nearly all of them. (In the fields today, the only Cesar Chavez most workers know is a famous Mexican boxer.)

The lessons the farmworkers learned about their own power lasted a lot longer than the contracts, but not nearly long enough.

Miriam Pawel is the author of “The Crusades of Cesar Chavez: A Biography,” winner of the 2015 Robert F. Kennedy Book Award.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.