Op-Ed: Why I’m trying to change how the FCC regulates the Internet

In 2012, Kevin Durant, James Harden and Russell Westbrook — all age 23 or younger — led the Oklahoma City Thunder to the NBA finals. But that team never got a chance to compete for another title, because the Thunder traded Harden away for fear that having three superstars would, someday, create salary cap concerns. How did that transaction work out? Harden is a perennial MVP contender for the Houston Rockets, Durant left for Golden State and Westbrook has struggled to hold the team together. Many Thunder fans would give anything to undo a trade motivated by speculative fears.

This story can be seen as a parable for Internet regulation. Two years ago, the federal government jettisoned an approach that was working in response to fears about what might happen at some point in the future. Beginning in the Clinton administration, there was for nearly two decades a broad bipartisan consensus that the best Internet policy was light-touch regulation—rules that promoted competition and kept the Internet “unfettered by federal or state regulation.” Under this policy, a free and open Internet flourished. The world’s most successful online companies blossomed right here in the United States. And American consumers benefited from unparalleled innovation.

In 2015, that approach changed dramatically. On a party-line vote, the Federal Communications Commission adopted heavy-handed government oversight of the Internet. Proponents of Internet regulation claimed that without new rules, the Internet would devolve into a digital dystopia of fast lanes and slow lanes, where service providers would treat traffic differently based on payments. And they argued that the only way for the government to prevent this outcome was to adopt an old regulatory framework called Title II—originally designed in the 1930s for the Ma Bell telephone monopoly—and apply it to thousands of Internet service providers, big and small. In other words, they wanted lawyers and bureaucrats to govern the Internet rather than engineers, technologists and businesses.

We can correct a past mistake by moving away from government control of the Internet.

Not surprisingly, this approach had problems. Most importantly, there was no evidence of the dysfunction that regulatory proponents feared. As Internet entrepreneur and Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban said in 2014 when opposing these new rules, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it…. There is no better platform in the world to start a new business than the Internet in the United States.” In the event of any demonstrated market failure, moreover, there were less intrusive options available.

Nonetheless, the FCC reclassified the Internet as a public utility under Title II, a disproportionate response akin to wielding the proverbial sledgehammer against a flea.

As I predicted when I voted against the order, infrastructure investment has declined since the FCC imposed Title II. Among our nation’s 12 largest Internet service providers, domestic broadband capital expenditures decreased by 5.6%, or $3.6 billion, between 2014 and 2016, the first two years of the Title II era. This was the first time that such investment declined outside of a recession in the Internet era. And small ISPs were affected disproportionately. Nearly two dozen of them recently told the FCC that its rules “affect our ability to find financing” and “hang like a black cloud.”

Because of Title II regulation, fewer Americans have high-speed broadband access, fewer Americans are working to build next-generation networks, and fewer Americans have competitive choice than would have been the case had the FCC not gone down the Title II path.

In 2015, the FCC also established a so-called Internet conduct standard, which gave the FCC a roving mandate to micromanage the Internet. Talk about a recipe for regulatory uncertainty. The FCC abused this newfound authority, as regulators are inclined to do, launching a wide-ranging investigation of free-data programs under which wireless customers can stream music, video and the like without limits. These programs are popular among consumers, particularly lower-income Americans, and make the wireless marketplace more competitive.

After becoming FCC chairman, I terminated this investigation. But it’s clear more comprehensive changes are warranted. That brings me to this week’s action.

On Wednesday, I formally proposed to repeal the mistake of Title II. If the FCC agrees at our next public meeting on May 18, we will seek public input on restoring the successful, bipartisan framework for promoting Internet freedom and infrastructure investment that the FCC abandoned in 2015. This framework will expand high-speed Internet access and help close the digital divide in our country. This framework will put more Americans back to work. And this framework will provide consumers more and better digital options.

James Harden’s contract doesn’t expire until 2020 and Kevin Durant is a warrior for Golden State, so the Oklahoma City Thunder’s short-term future seems cloudy. But at the FCC, we can correct a past mistake by moving away from government control of the Internet. And that’s exactly what we intend to do.

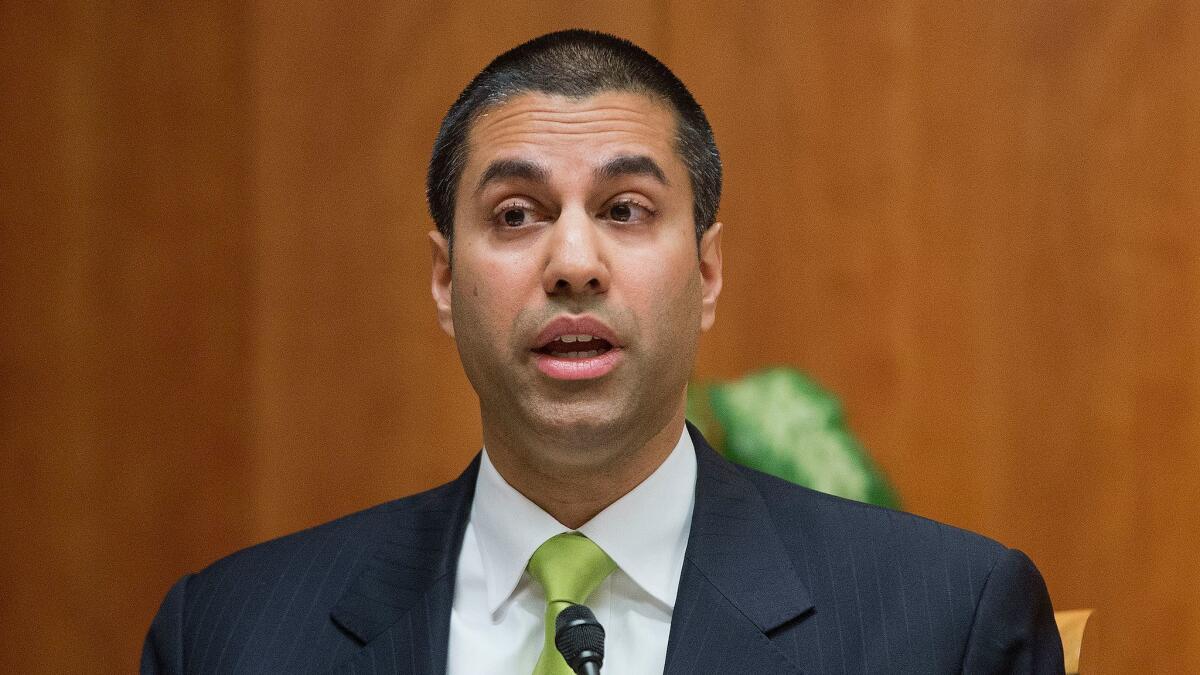

Ajit Pai is the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.