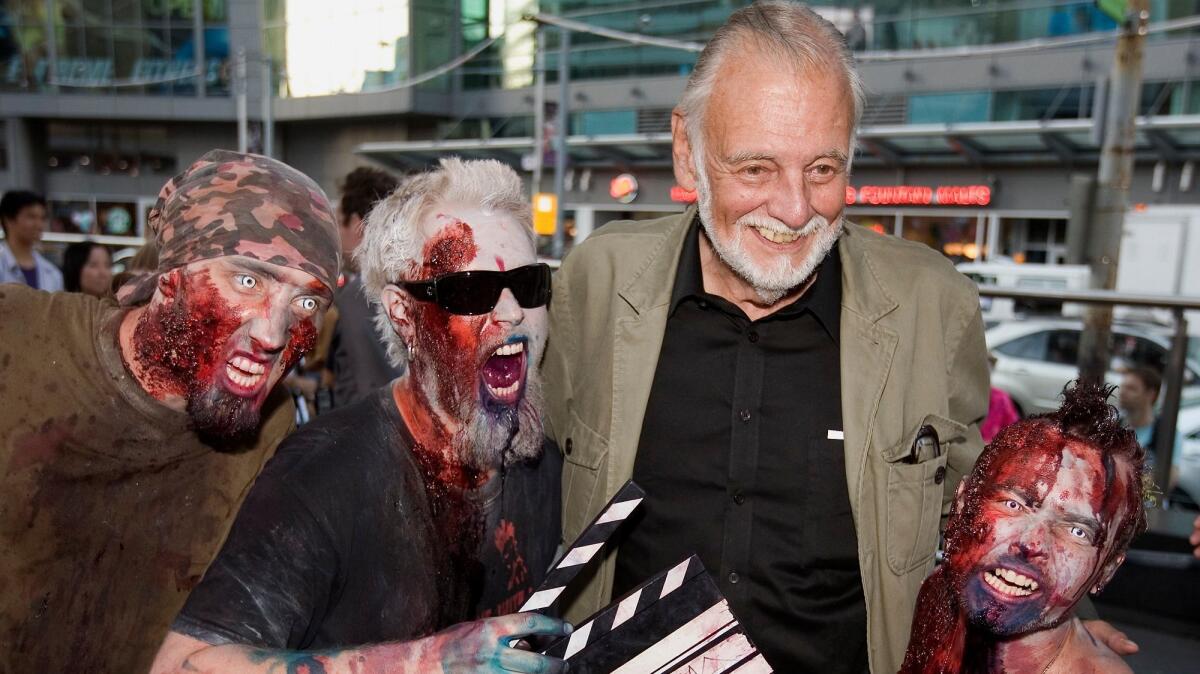

Op-Ed: How George Romero Americanized the zombie

When George Romero died Sunday, he was almost universally hailed as the father of the zombie movie. The title was both too much and not enough. Romero’s “The Night of the Living Dead” didn’t invent the zombie movie; that credit goes to “White Zombie” from 1932. But in his great trilogy — “Night of the Living Dead,” “Dawn of the Dead” and “Day of the Dead” — Romero reinvented the genre of the zombie movie so thoroughly that what before had been a minor subspecies of B-flick became a functioning allegory for the American way of life.

The figure of the zombie was not originally American, of course. It was a figure of fear and mortal terror developed in Haitian voodoo. Before the revolution, Haitian slaves believed that death would return them to lan guinee, or Guinea in Africa. But the zombie could not go home. He was a slave even in death. The notion of the zombie may have begun as colonists’ proscription against suicide; even in certain kinds of death there would not be liberation. The ultimate agony was to be a slave eternally.

Given this history, the zombie is perhaps the most grotesque of any major pop culture trope. When you wear a zombie costume, you are appropriating a Haitian narrative about the despair of slavery. In a time when a college lecturer can be forced to resign over an email about Halloween costumes, and a novelist can provoke outrage by wearing a sombrero to a lecture, it is remarkable that the zombie goes almost entirely unchallenged as a cultural icon. (“The Walking Dead” is in its seventh season.)

We have Romero to thank, I believe, not just for the popularity of zombies but for the transcendence of their specific, charged context. In 1932’s “White Zombie,” Bela Lugosi plays Murder Legendre, who owns a plantation in Haiti and uses the undead as laborers. A passing couple is visiting a neighboring plantation, and a love triangle emerges in which Madeleine, a white woman, is turned into a zombie. Hence the title. What was extraordinary in the original zombie movie is that white people could become zombies. That was the horror.

In a way, Romero excised history from the zombie narrative. No character in his trilogy refers to the monsters in question as zombies. In “The Night of the Living Dead,” they are “ghouls.” The word does appear in the script to “Dawn of the Dead” but mostly the creatures are referred to as “the dead” or simply “them.”

Not that the traditional roots of the zombie story were entirely removed. In “Dawn of the Dead,” Peter, played by Ken Foree, looks over a crowd of zombies: “They’re us, that’s all. There’s no more room in hell.” When his fellow survivors ask him what he means, he says, “Something my granddaddy used to tell us. You know Macumba? Voodoo? Granddaddy was a priest in Trinidad. He used to tell us, ‘When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.’”

Romero’s other key modification — against the “White Zombie” standard— was to make at least one of the heroes African American in each film in the trilogy. The zombies are mostly white. In “The Night of the Living Dead,” a black man fights off a bunch of unthinking rural white Americans who want to eat him. The movie ends with the hero being casually shot by a white paramilitary group evocative of a lynch mob.

Thus Romero took the real fear of the zombie — the fear of the loss of humanity — and placed it right at the heart of the American story. That’s what great cult films do.

He also gave that fear a contemporary analogue, turning American consumerism, rather than the plantation, into the soul-destroying force. “Dawn of the Dead” is not necessarily a great example of filmmaking craftsmanship or art, but its symbolism is immaculate. The scene in “Dawn of the Dead” when the survivors of the outbreak arrive in the middle of a zombie-infested suburban mall — this is genius. The wandering crowds look at mannequins. They want to look like the mannequins. They don’t know that they are already mannequins, mannequins that can move. They stumble from store to store because they vaguely remember real desires they once might have had.

Zombies, in Romero’s hands, are not super violent. Compared to the undead in “Resident Evil” or “28 Days Later” or “World War Z,” his zombies are quite gentle. Sure, they eat human beings, but mostly they stumble around bumping up against chain-link fences or boarded-up doors. You have to do something really dumb to be killed by a Romero zombie, like go down a mine shaft without a light or put a gun in its hand.

Except when they occasionally need to eat flesh, Romero’s zombies mostly just go about their business. That’s what’s so scary about them: They’re not that different from ordinary people.

Stephen Marche is the author, most recently, of “The Unmade Bed: The Messy Truth About Men and Women in the Twenty-First Century.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.