Op-Ed: Despite Tsarnaev, the death penalty is on the decline

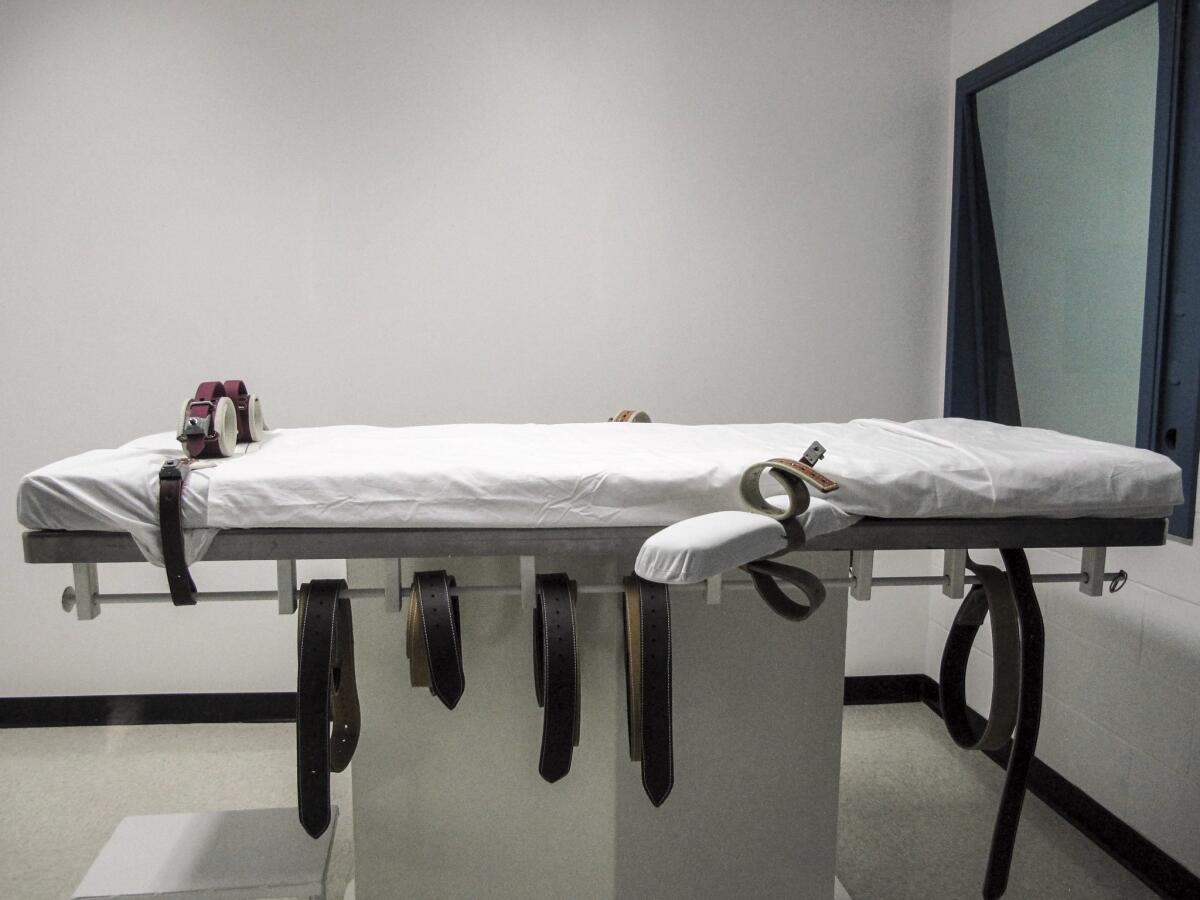

Nebraska’s lethal injection chamber at the State Penitentiary in Lincoln, Neb.

The execution of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev for his role in the Boston Marathon bombing — if it ever takes place — will quite possibly be the last of its kind, remembered as the last time the federal government put a person to death.

After a formal sentencing hearing next month, Tsarnaev’s lawyers are expected to request a new trial. As the case winds through the lengthy appeals process, the prosecution’s main argument for execution — that it offers “closure” to victims and their families — will be revealed as illusory. In effect, the appeals phase will put the death penalty on trial, and as time passes, public and legal opinion will probably turn decisively against the “ultimate punishment.”

Thirty-four U.S. states are “retentionist” — they still have some form of capital punishment on the books — and 16 states have executed a person in the last three years. But the number of executions and new death sentences is at a 20-year low, and just a few states are responsible for the vast majority of executions.

Many U.S. cities, and a number of states, are now anti-death penalty zones — not just liberal bastions like Berkeley and Cambridge, Mass., but also New Jersey, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland and New Mexico. A bill to reintroduce the death penalty in Massachusetts was defeated. Bills to outlaw the death penalty are in process in Delaware, Kansas and Colorado. Even in Nebraska, a conservative state, a bill to abolish the death penalty has such strong support that legislators could override an expected veto by the governor.

Meanwhile — and driving that change — recent developments have brought intense public scrutiny of this controversial practice.

This year two death row inmates were exonerated: Debra Milke, jailed from 1990 to 2013 in Arizona, and Anthony Ray Hinton, jailed since 1985 in Alabama by a prosecutor who said he knew Hinton was guilty “just by looking at him.” They were the 151st and 152nd U.S. death row prisoners so exonerated — the latest illustrations that the evidence in capital cases is often faulty or nonexistent.

Also this year, Utah reinstituted the practice of execution by firing squad, even though (as Gov. Gary Herbert put it) it’s “a little bit gruesome.” The move was a tacit admission that the lethal-injection procedure (which has changed as pharmaceutical companies have ceased production of several lethal drugs) is now so unreliable that shooting a man at close range is the more humane option.

Indeed, the medical establishment is increasingly uncomfortable with lethal injection. At its annual meeting in March, the American Pharmacists Assn. declared that “the practice of providing lethal-injection drugs is contrary to the role of pharmacists as healthcare providers,” thus joining associations of doctors and of anesthesiologists in deeming cooperation with executions contrary to the Hippocratic Oath (“first do no harm”).

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule in a case brought by prisoners on death row in Oklahoma, contending that the death penalty as carried out there — by lethal injections secretly arranged and shoddily administered — constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. It is the most substantive legal challenge to the death penalty here in decades. And it will put the court in the quixotic position of weighing the legality of the very procedure (lethal injection) that the Justice Department is brandishing as an instrument of justice in the Tsarnaev case.

The death sentence given to Tsarnaev is a final spasm of the death penalty, a punishment that the U.S. is on its way to abandoning, as most civil societies have already done.

When the Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe took place in 1975, 16 European countries had already abolished the death penalty or committed to doing so. By the time the Berlin Wall came down, there were 19. By 2002, 38 more countries around the world had done so, including much of the former Soviet Union.

Today 105 of the 192 countries represented at the United Nations have abolished the death penalty by law, and at least 43 more have abolished it in practice, either through public moratorium or de facto moratorium (when a country declines to practice capital punishment for a decade or longer). Those that still employ the death penalty — among them Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Egypt, Somalia, China, Japan and the U.S. — are outliers and strange bedfellows.

Of course, there is nothing to prevent future U.S. attorneys general from seeking the death penalty — for federal crimes involving terrorism and national security, for example — and future juries from delivering death sentences in capital cases. Societies and social norms, however, change quickly.

The last time a convicted criminal was executed in Massachusetts — 1947 — Harvard University was an all-male institution, “separate but equal” was still the law in much of the country, and the high wall in left field at Fenway Park had just been painted green. The last time the federal government executed a convicted criminal — Timothy McVeigh in June 2001 — the euro was a new currency, the Internet had only 50 million users and the World Trade Center towers were still standing.

President Obama, as he leaves office in 2017, could grant Tsarnaev clemency, reducing his sentence to life in prison without parole. But whether or not he does so, the long-term outlook is clear: In the United States today, the death penalty is itself on the verge of death.

Mario Marazziti is the author of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Death Penalty” and cofounder of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.