Op-Ed: Does the term ‘apartheid’ fit Israel? Of course it does.

The storm of controversy after Secretary of State John F. Kerry’s warning that Israel risked becoming an “apartheid state” reminded us once again that facts, data and the apparently tedious details of international law often seem to have little bearing on conversations about Israel conducted at the highest levels of this country. As was the case when other major figures brandished the “A-word” in connection with Israel (Jimmy Carter comes to mind), the political reaction to Kerry’s warning was instantaneous and emotional. “Israel is the only democracy in the Middle East, and any linkage between Israel and apartheid is nonsensical and ridiculous,” said California Sen. Barbara Boxer. That’s that, then, eh?

Not quite. Flat and ungrounded assertions may satisfy politicians, but anyone who wants to push the envelope of curiosity even a little bit further might want to spend a few minutes actually thinking over the term and its applicability to Israel.

“Apartheid” isn’t just a term of insult; it’s a word with a very specific legal meaning, as defined by the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid, adopted by the U.N. General Assembly in 1973 and ratified by most United Nations member states (Israel and the United States are exceptions, to their shame).

According to Article II of that convention, the term applies to acts “committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” Denying those others the right to life and liberty, subjecting them to arbitrary arrest, expropriating their property, depriving them of the right to leave and return to their country or the right to freedom of movement and of residence, creating separate reserves and ghettos for the members of different racial groups, preventing mixed marriages — these are all examples of the crime of apartheid specifically mentioned in the convention.

Seeing the reference to racial groups here, some people might think of race in a putatively biological sense or as a matter of skin color. That is a rather simplistic (and dated) way of thinking about racial identity. More to the point, however, the operative definition of “racial identity” is provided in the 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (to which Israel is a signatory), on which the apartheid convention explicitly draws.

There, the term “racial discrimination” is defined as “any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.”

A few basic facts are now in order.

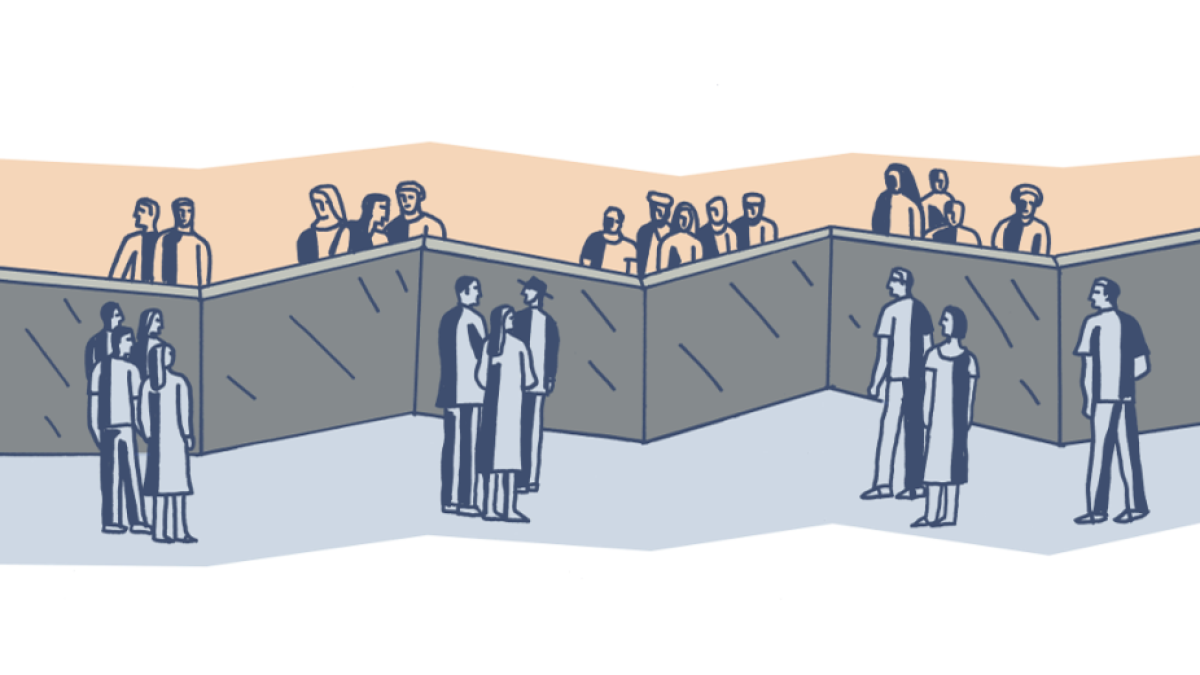

The Jewish state (for so it identifies itself, after all) maintains a system of formal and informal housing segregation both in Israel and in the occupied territories. It’s obvious, of course, that Jewish settlements in the West Bank aren’t exactly bursting with Palestinians. In Israel itself, however, hundreds of communities have been established for Jewish residents on land expropriated from Palestinians, in which segregation is maintained, for example, by admissions committees empowered to use ethnic criteria long since banned in the United States, or by the inability of Palestinian citizens to access land held exclusively for the Jewish people by the state-sanctioned Jewish National Fund.

Jewish residents of the occupied territories enjoy various rights and privileges denied to their Palestinian neighbors. While the former enjoy the protections of Israeli civil law, the latter are subject to the harsh provisions of military law. So, while their Jewish neighbors come and go freely, West Bank Palestinians are subject to arbitrary arrest and detention, and to the denial of freedom of movement; they are frequently barred from access to educational or healthcare facilities, Christian and Muslim sites for religious worship, and so on.

Meanwhile, Palestinian citizens of Israel must contend with about 50 state laws and bills that, according to the Palestinian-Israeli human rights organization Adalah, either privilege Jews or directly discriminate against the Palestinian minority. One of the key components of Israel’s nationality law, the Law of Return, for example, applies to Jews only, and excludes Palestinians, including Palestinians born in what is now the state of Israel. While Jewish citizens can move back and forth without interdiction, Israeli law expressly bars Palestinian citizens from bringing spouses from the occupied territories to live with them in Israel.

The educational systems for the two populations in Israel (not to mention the occupied territories) are kept largely separate and unequal. While overcrowded Palestinian schools in Israel crumble, Jewish students are given access to more resources and curricular options.

It is not legally possible in Israel for a Jewish citizen to marry a non-Jewish citizen. And a web of laws, regulations and military orders governing what kind of people can live in which particular spaces makes mixed marriages within the occupied territories, or across the pre-1967 border between Israel and the occupied territories, all but impossible.

And so it goes in all domains of life, from birth to death: a systematic, vigilantly policed separation of the two populations and utter contempt for the principle of equality. One group — stripped of property and rights, expelled, humiliated, punished, demolished, imprisoned and at times driven to the edge of starvation (down to the meticulously calculated last calorie) — has withered. The other group — its freedom of movement and of development not merely unrestricted but actively encouraged — has flourished, and its religious and cultural symbols adorn the regalia of the state and are emblazoned on the state flag.

The question is not whether the term “apartheid” applies here. It is why it should cause such an outcry when it is used.

Saree Makdisi, a professor of English and comparative literature at UCLA, is the author of “Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.