Op-Ed: Trump will fire Robert Mueller eventually. What will happen next?

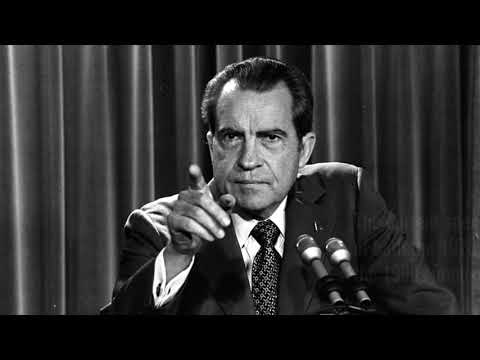

The current special counsel system is a legacy of both the 1970s Watergate scandal and the 1990s impeachment of Clinton.

A strange quiet has settled in at the White House.

President Trump greeted Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel in charge of the Russia investigation with a steady stream of diatribes, including some 40 bilious tweets. He challenged Mueller’s impartiality and called the investigation a “witch hunt.” But for nearly two months, Trump has restrained himself on the subject. His lawyers, meanwhile, have treated Mueller with customary deference.

The lawyers have accomplished what 16 Republican candidates, beauty pageant contestants, military heroes and a federal judge could not: They have muzzled Donald Trump.

How long can it last?

The president’s newfound reserve is certainly a smarter policy, and the one that white-collar lawyers routinely order their clients to follow. It’s not just a matter of avoiding antagonizing the prosecutor who holds the power to bring charges against you; every tweet can come back to bite you at trial, where skillful prosecutors can mine small inconsistencies.

Each turn of the screw of the Mueller investigation — and there will be many — increases the pressure on Trump to act preemptively.

But there’s no doubt that the Mueller investigation continues to rankle. Former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon argued in a recent “60 Minutes” interview that the firing of former FBI Director James Comey, which resulted in Mueller’s appointment, was one of the worst mistakes in modern political history. “I don’t think there’s any doubt that if James Comey had not been fired,” Bannon opined “[w]e would not have the Mueller investigation and the breadth that clearly Mr. Mueller is going for.”

The recent report that Trump savaged Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions when he learned of Mueller’s appointment — calling him an “idiot” and telling him he should resign — brings home the president’s extreme fear and loathing of the Russia investigation.

Which spurs three questions: 1) Will Trump one day try to oust Mueller? 2) If he does, will he get away with it? and 3) What consequences would that have for our political culture?

*

Here’s predicting flat out that yes, at some point Trump will try to oust Mueller.

As the probe advances, the likelihood increases that Mueller will uncover evidence of a serious offense by Trump. With the recent search of former campaign manager Paul Manafort’s home, Mueller has shown his willingness to follow the money trail aggressively. (The latest reports suggest that Mueller’s team is planning to indict Manafort for possible tax and financial crimes.) And Mueller has begun to negotiate interviews with up to a dozen White House aides as well as former White House officials. Trump likely fears that Mueller will zero in on something sleazy or criminal whose revelation could cripple his presidency. Each turn of the screw of the Mueller investigation — and there will be many — increases the pressure on Trump to act preemptively.

The odds also seem great that the erratic, power-consumed and thin-skinned Trump, who every week launches a new Twitter attack on a real or imagined enemy, will be unable to stay his hand month after month as the Mueller investigation unfolds. Like the fabled scorpion who stings the frog even though it dooms him, Trump, being Trump, won’t be able to endure domination by Mueller over the long term. Of course, Trump likely fails to appreciate that it is not Mueller personally, but the law, that is asserting its dominance.

Let’s say Trump snaps.

To fire Mueller, Trump would need to order Deputy Atty. Gen. Rod Rosenstein to remove him. But Rosenstein, a career prosecutor with a strong dedication to the values of the Department of Justice, would likely resign his office rather than comply with the order, as would the department’s third-ranking official, Rachel Brand.

Eventually Trump, moving down the hierarchy, would find someone willing to fire Mueller (as Nixon found Robert Bork, the then-solicitor general, to fire Archibald Cox).

From there, Mueller could launch a legal challenge to the ouster (potentially with the support of the Department of Justice). It’s by no means clear that Mueller, an ex-Marine of legendary rectitude, would choose to sue. Assuming he did, though, he would need to overcome a series of constitutional arguments by the president’s lawyers that any restrictions on the president’s ability to terminate him would impinge on presidential power under Article II.

In any event, any pushback from the courts would likely be procedural and incremental. Only Congress is positioned to pass broad judgment on Trump. But a congressional response — for example, a statute to create an independent counsel — would be tempered by political compromise, and would have to withstand a presidential veto. In particular, it’s hard to envision a scenario in which Congress successfully forced Trump to reinstate Mueller.

As for a more definitive rebuke such as impeachment, for now it is a barely conceivable fantasy. Even if Democrats were to gain control of the House in the 2018 elections, chances are remote that Democrats in the Senate would be able to muster the 67 votes needed to convict and remove. The trial would be a sort of opéra bouffe with Trump at the center at his most melodramatic. And when Trump is acquitted, he will find a cheap salesman’s way to declare victory, to the exasperation of his critics.

Impeachment without removal, then, looks to be the worst-case scenario for Trump. He’ll still get away with firing Mueller, but expect him not to run for a second term. Expect him also to be a fixture on, and probably atop, lists of the nation’s worst presidents.

Still, once Trump is out of office, and assuming he hasn’t left visible wreckage beyond an ousted independent counsel, can we then count ourselves lucky and move on from the misadventure?

Hardly. The difference between robust societies such as the U.S. and United Kingdom and autocratic ones such as Turkey and Russia is not the degree of formal constitutional protections. Russia’s Constitution purports to protect and empower its citizens every bit as much as ours. But weary experience leads Russian citizens to doubt that the law applies equally to all persons, or that political institutions are strong enough to prevent despotism. The result is a deep social and political cynicism.

In the scenario outlined above, in which Trump faces, at the very worst, impeachment without removal, he won’t have completely undone the norms, but he will have eroded them. His tenure will have moved the line of the conceivable.

We think that autocratic interludes are impossible here; they will seem a bit less so after Trump. After Trump, it will seem to many a little less certain that the rule of law will win out even against the rich and powerful; that government is transparent; that the free press can hold elected officials accountable; and that leaders cannot profit from government service. Restoring these assumptions to their pre-Trump levels will take time and good fortune.

Harry Litman, a former United States attorney and deputy assistant attorney general, teaches at UCLA Law School and practices law at Constantine Cannon.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.