Op-Ed: Dr. Larry Nassar was not a doctor

The 156 women who spoke in open court this week, chronicling Larry Nassar’s 20-year career as a sexual predator, seethed. They were unsparing. They were implacable. They were also brilliantly sardonic.

With icy contempt, they pronounced the oily phrases that Nassar and his enablers used to groom, manipulate and stigmatize them. Nassar was advertised to them as a “miracle worker,” a “knight in shining armor.” His sexual assaults were a “medical procedure.” But the survivors reserved special disdain for one word: “doctor.”

For the record:

5:50 p.m. Jan. 29, 2018This article originally stated that McKayla Maroney accused both the United States Olympics Committee and USA Gymnastics of paying to stop her from speaking out against Larry Nassar. Maroney did not claim that USOC was party to the financial settlement. However, Maroney named USOC (as well as USAG and Michigan State University) in a lawsuit concerning the settlement and charged that USOC was aware of Nassar’s misconduct.

“What kind of ‘doctor’ can tell a 13-year-old they are done growing by the size of their pubic bone?” Arianna Guerrero, one victim, asked. “‘Doctors do no wrong, only heal,’” said Jade Capua. Clasina Syrovy sideswiped Nassar with barbed grandeur, calling him “the ‘almighty and trusted gymnastics doctor.’”

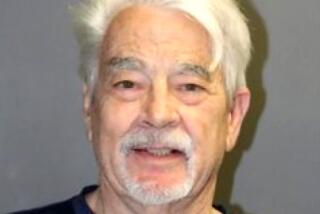

McKayla Maroney, the Olympic gold medalist who says she was paid $1.25 million by USA Gymnastics to stop her from speaking out, put it flatly: “Dr. Nassar was not a doctor.”

No wonder the survivors chose to crush that word. “Doctor” was Nassar’s supreme and founding lie. It notarized him as a professional pledged to heal, and launched his 20-year child-molestation spree, gaining him a sturdy disguise, a complicity network, access to victims and a savage sense of entitlement.

What allowed Nasser to use the honorific? In 1993, he received a doctorate in osteopathic medicine from Michigan State University. MSU, of course, went on to protect and pay Nassar, the almighty and trusted doctor, as a faculty member for 20 years. Lou Anna Simon, MSU’s president, resigned this week amid charges that the university covered for Nassar and enabled him. USA Gymnastics, where Nassar also passed as a doctor, is similarly accused of giving safe harbor to a known criminal, while hushing and deceiving his victims. Under pressure, the group announced this week that the entire USAG board would resign.

When you’re a star doctor, you can do anything.

Osteopathic medicine focuses on the joints, muscles and spine. Historically, though, osteopathy — its original name — was closely associated with a set of esoteric massage styles that some researchers now consider ineffective or worse. For its part, MSU’s College of Osteopathic Medicine still teaches these unusual manipulations — a special “benefit” unique to osteopathic medicine — describing them as a form of “hands-on diagnosis and treatment.”

Some historical context: Andrew Taylor Still, the founder of osteopathy, wrote of his medical discoveries in 1897: “I could twist a man one way and cure flux … shake a child and stop scarlet fever … cure whooping cough in three days by a wring of the child’s neck.”

Modern osteopathic medicine uses none of these techniques to treat infections — or anything else. But the specter of violence and child abuse that Still conjured in his early writings continues to haunt the fringes of osteopathic medicine. These practices include intravaginal manipulation. Fisting. This was the “medical procedure” Nassar performed on so many young girls.

According to his victims, Nassar’s attention wasn’t on their hamstrings or ACLs; instead, he focused on their anuses, breasts and vaginas. In January 2017, one victim spelled it out in her complaint: “Nassar digitally penetrated Plaintiff Jane A. Doe’s vagina multiple times without prior notice and without gloves or lubricant.” Other victims describe Nassar’s forcing his “dry fingers” into their anuses and vaginas. The violent fisting was excruciating. “I’d want to scream,” said Kassie Powell, an MSU pole vaulter. As Amy Labadie, a gymnast, put it: “My vagina was sore during my competition because of this man.”

Then came the gaslighting. When the girls blew the whistle, Nassar and his enablers tirelessly reasserted his privileges as a doctor. “We were manipulated into believing that Mr. Nassar was healing us as any normal doctor is supposed to do,” Capua testified. Just last year, the American Osteopathic Assn. released a statement to MLive.com, the Michigan news service, saying that intravaginal manipulations are indeed an approved, if rare, osteopathic treatment for pelvic pain.

No need to fact-check that. Grabbing a young woman inside the vagina is not a first-line or thousandth-line treatment for anything. The victims knew this intuitively, but over and over they were told to doubt their perceptions, suppress common sense in favor of mystifying quackery and accept their unerring reflex to recoil from Nassar’s probes as their own failure. The takeaway was this, to paraphrase the president: When you’re a star doctor, you can do anything.

Nassar’s story may seem like an outlier, but it’s only the latest entry in the master narrative of our time. A powerful man, abetted by a syndicate of sponsors and enablers, commits a violent or sky-high crime — rape, sexual abuse of children, torture, murder, conspiracy with a hostile foreign power, treason — and then moves heaven and Earth to conceal it, deride those who expose it as fake news, and smear the victims and whistleblowers. Trump. Putin. Ailes. O’Reilly. Weinstein. Wynn. And Nassar.

In April, following his arrest four months earlier, Nassar’s medical license was finally revoked. His vocation is now lifetime incarceration. Nassar is no longer a doctor, and perhaps, as the women have proposed, he never was. Their graphic, incantatory statements may dispel the fog: They inscribe reality into the record for the first time — and for all time.

Twitter: @page88

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.