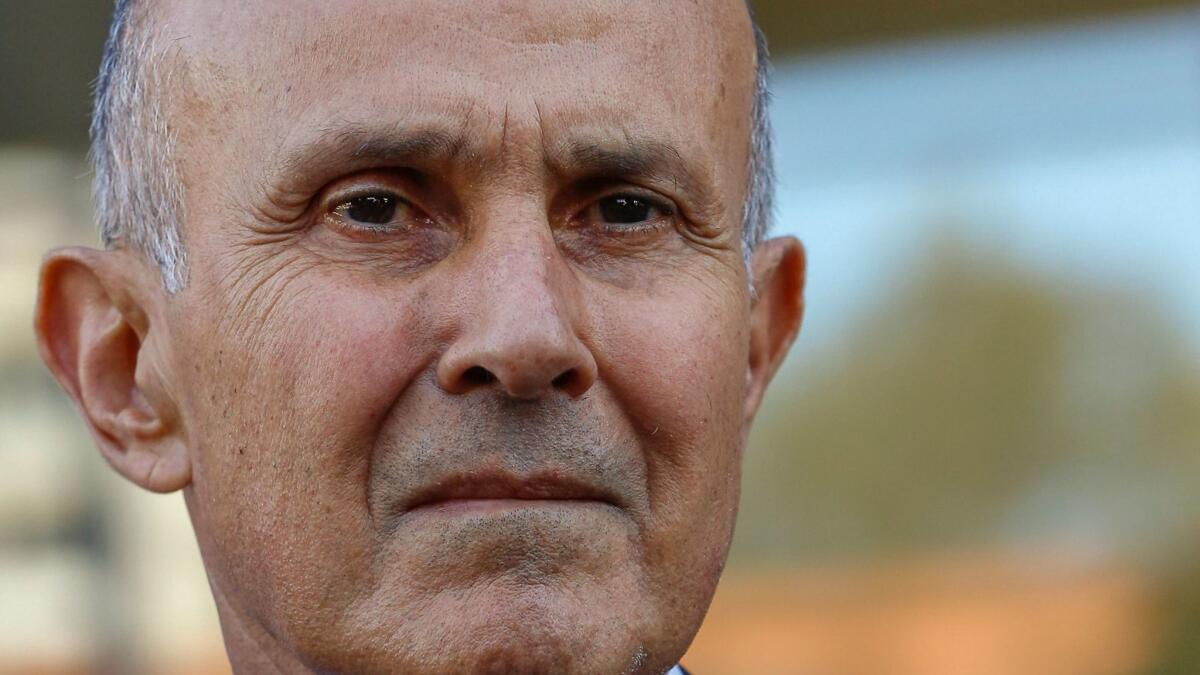

Op-Ed: The warning signs L.A. County missed when voters reelected Sheriff Lee Baca

Lee Baca will be sentenced Friday morning for lying to federal officials and conspiring to obstruct an FBI investigation into the corruption and brutality that plagued the agency he presided over as Los Angeles County sheriff.

For 15 years, Baca headed the largest sheriff’s department in the world. It polices 40 cities and 90 unincorporated communities in 4,057 square miles of Southern California, and it oversees 18,000 inmates in the county’s seven jails. Baca was elected five times by large margins. Yet, over the last four years, 21 sworn members of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department have been convicted of or pleaded guilty to charges ranging from obstruction of justice to serious civil rights abuses.

How can we keep this from happening again?

In the beginning, the county liked Lee Baca for a reason. His progressive actions were many and genuine. He spoke frequently of opposing the “warrior” cop school of policing in favor of a more community-centric, humane model. He brought NFL great Jim Brown’s much-praised Amer-i-Can counseling program into the jails. He was an early and active supporter of gang-intervention programs. After 9/11, he began visiting mosques and meeting with Muslim American leaders all over the county, and, at a congressional hearing, Baca famously stood up to a congressman who made Islamophobic comments.

Had the county insisted on rigorous independent civilian oversight, perhaps we could have nurtured Baca’s better angels.

Over time, however, there were warning signs the media, and the electorate, should have heeded.

One major indication that all was not well was a parade of yearly reports delivered by the Southern California ACLU claiming a pattern of abuse of inmates in the L.A. County jail system, along with a matching parade of high-ticket civil lawsuits. But lawsuits move ponderously; and Baca’s spokespeople routinely dismissed inmates’ abuse claims as untrue.

The few whistleblowers who emerged from inside the system were quickly silenced by the department. In June 2003, jailhouse minister Javier Stauring was banned from county lockups for speaking out. And neither the media nor the public managed to get all that riled about likely lawbreakers getting whacked around by clean-cut guys with badges.

The horrific reality that groups of jail deputies were permitted to engage in a reign of terror began to capture our attention in September 2011, when the ACLU issued a report that included compelling videos. A year later, the seven-member Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence appointed by the county Board of Supervisors, issued its own blistering report. Finally, the FBI’s multi-year investigation began producing indictments, forcing us belatedly to come to terms with what Baca had allowed to flourish in the jails: “a toxic … culture of corruption seen only in the movies,” in the words of one FBI supervisor.

All along, L.A. County’s well-liked sheriff displayed worrisome symptoms of character drift that we ignored. In the 1990s, he cultivated celebrities and wealthy benefactors by making them honorary deputies and giving them concealed-weapons permits. He asked President Clinton to pardon convicted cocaine smuggler Carlos Vignali, whose father was a generous campaign donor. He gave all-but-free passes to glitzy arrestees such as Mel Gibson and Paris Hilton.

The most glaring warning sign was the matter of whom the sheriff trusted most. The name that stands out is former Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, Baca’s second in command. Tanaka is now four and a half months into a five-year sentence in Colorado for obstruction of justice.

As far back as 2004, when he held the rank of chief, Tanaka was known as Baca’s crown prince, who would one day succeed his boss and until then, the man who could make or destroy any department member’s career with a phone call.

Even now, many of Baca’s closest friends and supporters portray the former sheriff as a victim of Tanaka’s ambition and trickery, a characterization that is too simple. For years, colleagues and personal friends warned Baca that Tanaka promoted a “work the gray” attitude in policing. As the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence put it, Tanaka not only failed to “identify and correct” problems of brutality in the department, “he exacerbated them.”

Yet Baca brushed off any criticism of his protégé. In a recorded deposition played for jurors in his March trial, Baca confided that Tanaka “had a unique talent of doing exactly what I wanted done.” The sheriff was willingly seduced. It would cost him everything.

Had the county insisted on rigorous independent civilian oversight, perhaps we could have nurtured Baca’s better angels. But Merrick Bobb, the special counsel to the supervisors, and the Office of Independent Review, had no real power. The new Office of the Inspector General and the newer Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission may fare better. Early signs seem promising, yet their collective lack of any kind of legal authority is troubling.

In late July, 2012, the lead attorney for the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, asked Baca the question that had long plagued department critics then, and still challenges us now.

“How do we hold you accountable?”

Baca paused for two beats, then smiled.

“Don’t elect me,” he said.

And yet we did. Over and over.

Baca is now 74 and suffering from early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. He may do no prison time, or perhaps U.S. District Court Judge Percy Anderson will go well above the two years that government prosecutors have recommended. Those of us who re-elected him also deserve judgment. We simply weren’t vigilant enough.

Celeste Fremon is editor and founder of the non-profit criminal justice news site WitnessLA.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook.

ALSO

Judgment day for convicted ex-Sheriff Lee Baca, and the end of a long-running scandal

The rise and fall of Lee Baca, L.A. County’s onetime ‘Teflon Sheriff’

Sheriff whistleblower who testified in federal obstruction case gets $1.275-million settlement

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.