Robert Gates’ failure of duty

In a dozen years of war, Americans have grown used to improvised explosive devices. The detonations have rocked the streets of Kabul and Baghdad — and also of Washington. Only, in Washington, the bombshells appear in print.

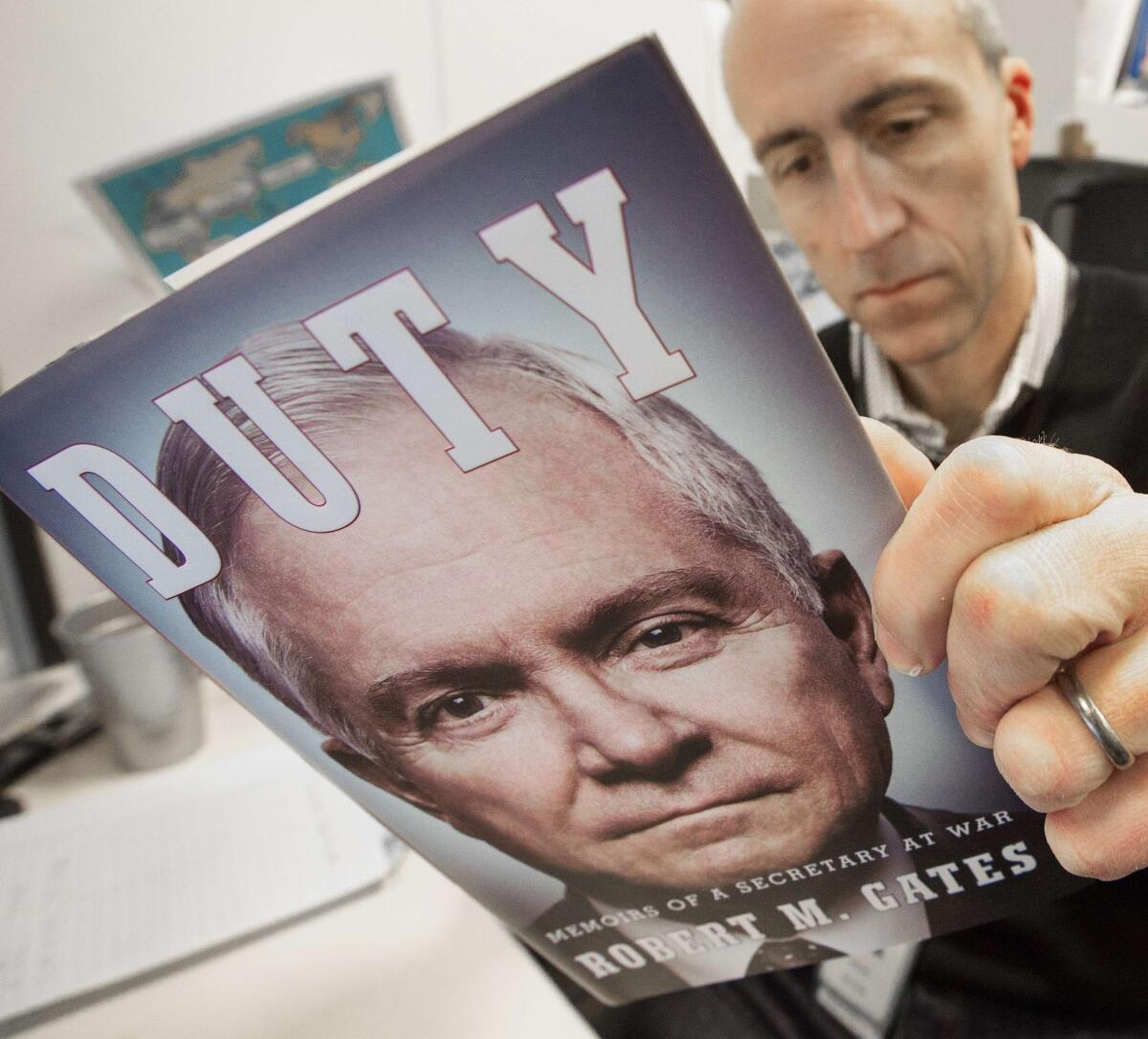

The latest domestic blast, a diatribe called “Duty” by former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, seems to have startled even the dean of White House correspondents. “It is rare for a former Cabinet member,” wrote Bob Woodward in the Washington Post, “let alone a Defense secretary ... to publish such an antagonistic portrait of a sitting president.”

Yet, as can happen with IEDs, the shrapnel from this one may wound its originator more severely than its intended targets. From the excerpts of the memoir that have been released, Gates emerges as a petulant, inhibited man who ill-served his president and the national interest by keeping his anger and concerns bottled up instead of raising them in person, at the time when it might have done his country some good.

His criticism of President Obama’s handling of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, moreover, is fixated on U.S. troops and on executive branch infighting. It fails to examine the most profound flaw in the conduct of the wars: the lack of an overarching policy within which troop deployments might have made sense.

Especially toward the end of his tenure, Gates would let fly with an occasional caustic remark. But he was known in the Pentagon, where I worked at the time, for his understatement. Often the last to comment in meetings of top officials where national security decisions were made, he saved his fire until he had heard where his colleagues came down.

But the Gates who emerges in this self-portrait is hopping mad, constantly struggling to contain the boiling inside. “My initial instinct was to storm out,” he said of a National Security Council meeting, one of many moments when he writes he almost quit. “It took every bit of my self-discipline to stay seated on the sofa.”

Hiding thoughts and feelings, presenting an impassive face to the outside world, is often seen as a rugged, manly virtue. In this case, it was a failing.

I think I would have given 10 years off my life, maybe amputated a limb, for the chance to spend half an hour with Obama during the same period Gates covers in his book. I was working on high-level Afghanistan policy, having lived in that country since 2002. I desperately wanted to provide an analysis of the drivers of the conflict — and associated policy recommendations — that I knew Obama was not getting from his Cabinet or his White House aides.

As secretary of Defense, Gates could meet the president whenever he needed to. And yet, by his own admission, he never mentioned his concerns. Those concerns, especially regarding what he calls White House micromanagement, are shared by other former officials who have spoken out. But it is just such issues that responsible top executives routinely raise and work through with their superiors.

Likewise the widening breach of trust that Gates and others describe separating the White House and top military brass. Gates decries the national security staff’s “aggressive, suspicious and sometimes condescending and insulting questioning of our military leaders.” Yet he never rose to those leaders’ defense by having a forthright conversation with the president to call out this conduct. If it was as damaging to him and to the national interest as he writes, it was his duty to do so.

On substance, Gates praises Obama’s decision to authorize the raid that killed Osama bin Laden. He criticizes his ambivalence about the troop surge in Afghanistan. But in each case, what Gates neglects to highlight is the lack of a coherent policy framing the military actions.

Bin Laden’s compound — given its size, the loops of concertina wire protecting its walls and its location in the heart of a highly secure military town — was, on the face of it, a safe house. And yet, while top executive branch officials and even the president were debating how many helicopters should fly on the raid, no one worked through all the implications for Pakistan policy. Was our ally in the Afghanistan war deliberately harboring our No. 1 enemy? What did that mean? How should our approach to Pakistan change?

None of those questions was sufficiently examined during the lead-up to the raid. And in the subsequent policy scramble, a coherent strategy toward that counterproductive partner was never developed. The U.S. is still subsidizing a government that deliberately organizes and sends extremists to commit attacks in Afghanistan.

Gates blasts Obama’s growing ambivalence about the “troop increase [he] boldly approved in 2009.” The massive deployment was, in Gates’ view, a better approach than whack-a-mole counter-terrorism. And yet, without a policy to grapple with the abusive corruption of the Afghan government or with Pakistan’s sponsorship of the Taliban, neither of those military options stood much chance of success. Without such a strategic framework, Obama was right to be dubious about the surge. Where he was wrong was in failing to task his civilian leadership to adequately develop that policy.

“Duty” will go down as one of the most ill-tempered memoirs ever written by a former Cabinet secretary. The White House helped bring such a tongue-lashing on itself by relentlessly spinning this story for years, through interviews and leaks to authors like Woodward. Still, Gates may have tarnished his previously stellar name by retorting in this manner, at this time.

Sarah Chayes, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a contributing writer to Opinion, served as special assistant to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 2010 to 2011.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.