Op-Ed: Most New Year’s resolutions fail. If you want yours to succeed, put some money behind it

In the next few days millions of Americans will make New Year’s resolutions — and about a third of those will have something to do with improving health and fitness. Lose weight (12%), eat better (9%) and exercise more (9%) are three of the most common goals, according to polling from the Marist Institute for Public Opinion.

We already know that most will fail. If you’re serious about not abandoning your resolutions before Groundhog Day, let behavioral economics lend a hand.

The first thing to do is set a specific, but rational, target. Too many people skip over this part because they think they know how to measure success: They’ll be able wear their favorite skinny jeans again.

But it’s unreasonable, for instance, to set a goal of losing more than 10% of your current weight. A study of obese dieters, by contrast, found that most wanted to lose more than 30% of their initial weight. The sad truth is that short of undergoing gastric bypass surgery, most people don’t lose that kind of weight, let alone keep it off. Only about 1 in 5 successful dieters are able to maintain a 10% weight loss for at least a year. It’s hard work to join the 10% club, but it’s even harder to remain a member.

Each week I will either lose one pound or I will forfeit $500 to a political action committee that I oppose.

Likewise, resolutions for fitness and eating better should be attainable, and success should be measurable on a weekly basis: Logging 10,000 Fitbit steps each week, or taking your lunch to work and not drinking soda. Inputs are often more under your control than results. Resolving to exercise three times a week might be better than resolving to bench press 150 pounds.

Once you have the right goal, you need the right incentives.

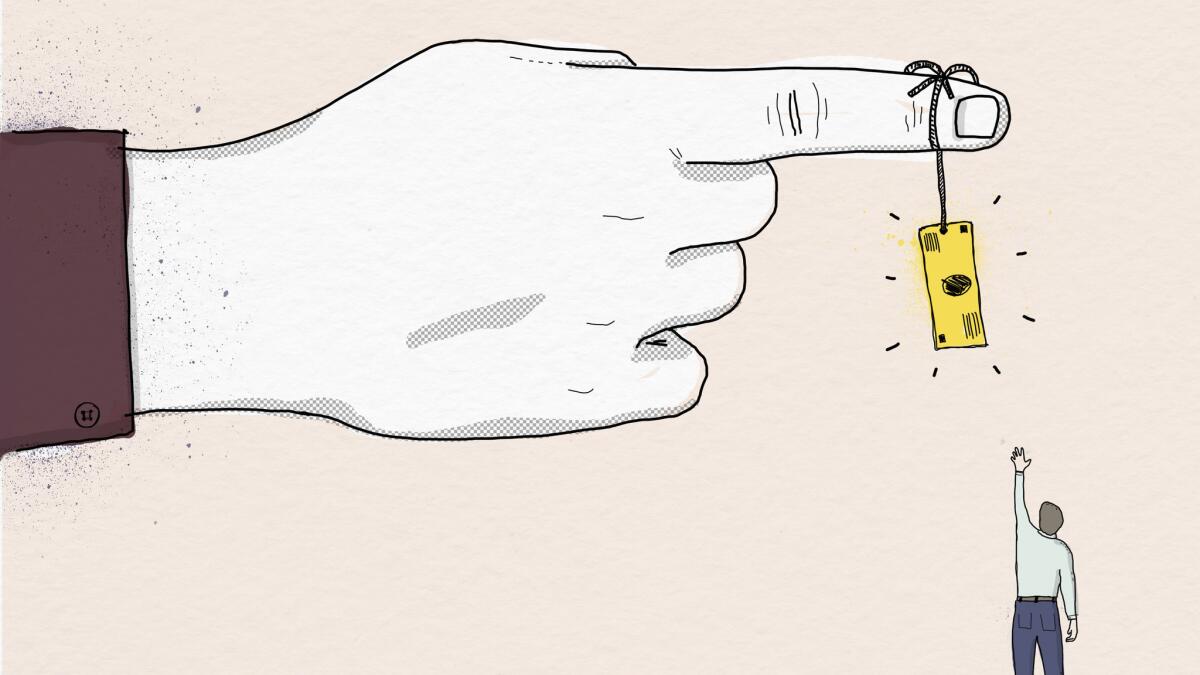

We treat getting into shape as an information problem, and spend freely on diet and fitness books. What we should do with our money is stiffen our resolve. Personally, I’m going to put some meaningful money at risk for the next several weeks to help me reach my weight loss goal. Each week I will either lose one pound or I will forfeit $500 to a political action committee that I oppose.

I’ve used this kind of commitment contract several times in the past and it’s worked like a charm. Every week when confronted with the stark choice of whether I want to forfeit $500, I’ve found it easy to forgo dessert and hit the gym.

I might instead have looked for a rich relative to offer me some prize if I reached my goal weight, but behavioral economics teaches that carrots aren’t as effective as sticks. I’ll work harder toward my goal because the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.

The suggestion of putting $500 at risk will probably scare a lot of people away from even considering this method of keeping resolutions. Who wants to go broke trying to slim down or get in better shape? But the beauty of this approach is that it can be free. A commitment contract uses the threat of losing a chunk of cash to increase the likelihood that you will persist toward your goal. A financial penalty for missing your weekly target literally increases the cost of eating or failing to use your gym membership. But it’s a price you need not pay.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

You could enter into this kind of a contract with a friend or family member who can also adjudicate whether you succeed. One of my colleagues has had a commitment contract in place for more than 20 years: She vowed to pay a friend $10,000 if she ever smokes another cigarette.

If risking $500 a week is too rich for your blood, choose a smaller but meaningful amount. Think about how much you spend each week on things that you enjoy (lattes at Starbucks, or Saturday-night movies) and put those privileges at risk. Everyone has the ability to put 10% or 20% of their discretionary income at stake.

Many New Year’s resolutions are only half-intended from the get-go. But if you’re serious about improving your health or fitness, a commitment contract can give you hundreds of reasons to see it through each week.

Ian Ayres is a professor at Yale Law School, the author of “The $500 Diet” and a co-founder of the commitment contract site StickK.com.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.