Op-Ed: How doctors fought to save Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, and lost

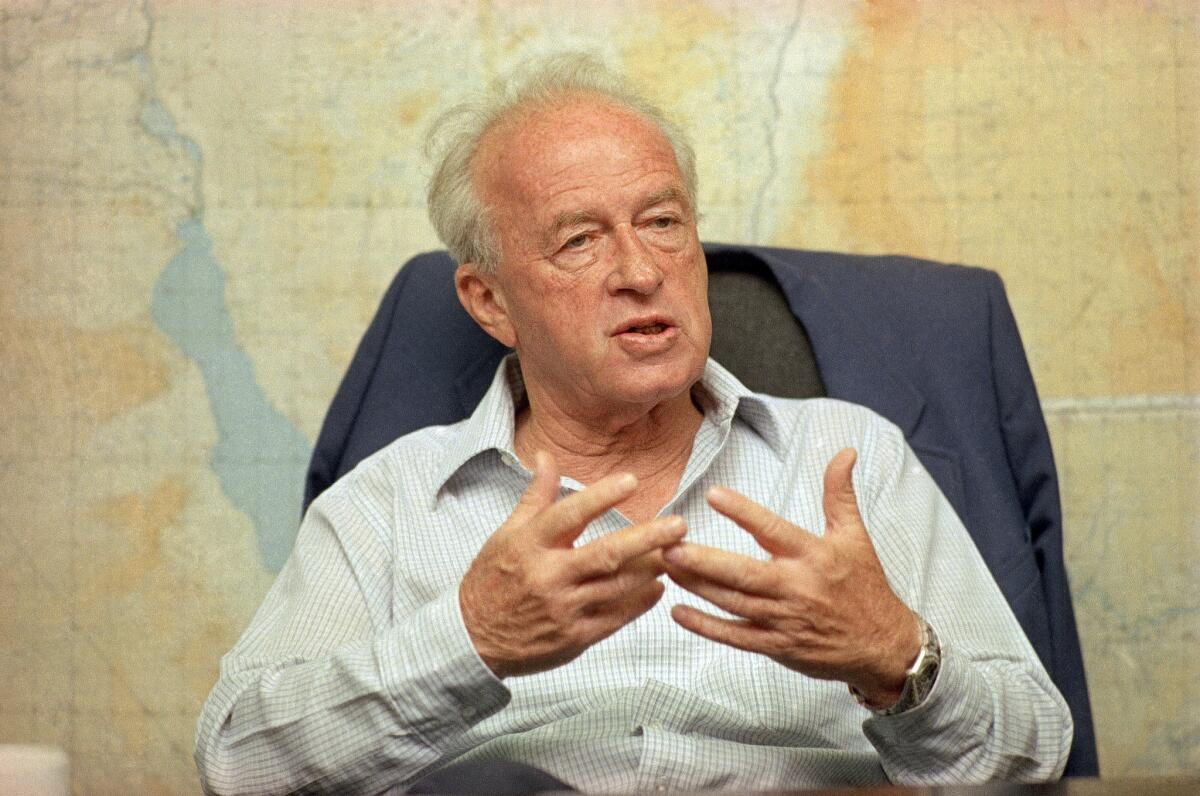

A portrait of late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in Tel Aviv, Israel on Oct. 28. In 1995, Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing Israeli minutes after attending a festive peace rally.

Twenty years ago today, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish extremist opposed to his peace deals with the Palestinians, known as the Oslo Accords. The gunman, a 25-year-old law student, shot Rabin in a parking lot at the end of a rally in Tel Aviv. In this excerpt from the new book “Killing a King: The Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin and the Remaking of Israel,” author Dan Ephron describes the dramatic moments in the Ichilov hospital after the shooting.

In the emergency room, Yitzhak Rabin was not breathing and had no pulse. The doctor on call, Nir Cohen, noted the bullet wounds in Rabin’s back and then turned him over to examine his chest. Only then, when he bent down to listen to his lungs with a stethoscope, did Cohen realize this elderly man in his elegant suit was the prime minister. Other doctors gathered around his bed while a nurse phoned the surgery department: send people now, she said. Mordechai Gutman, the most senior surgeon in the building, came running. The emergency-room doctors had pulled off Rabin’s jacket and shirt by now and inserted an IV. Gutman, sensing that air had seeped into Rabin’s right chest cavity, plunged a tube into his rib cage to drain it. A gust of air and blood burst from the cylinder. Suddenly, a pulse appeared; the prime minister was alive.

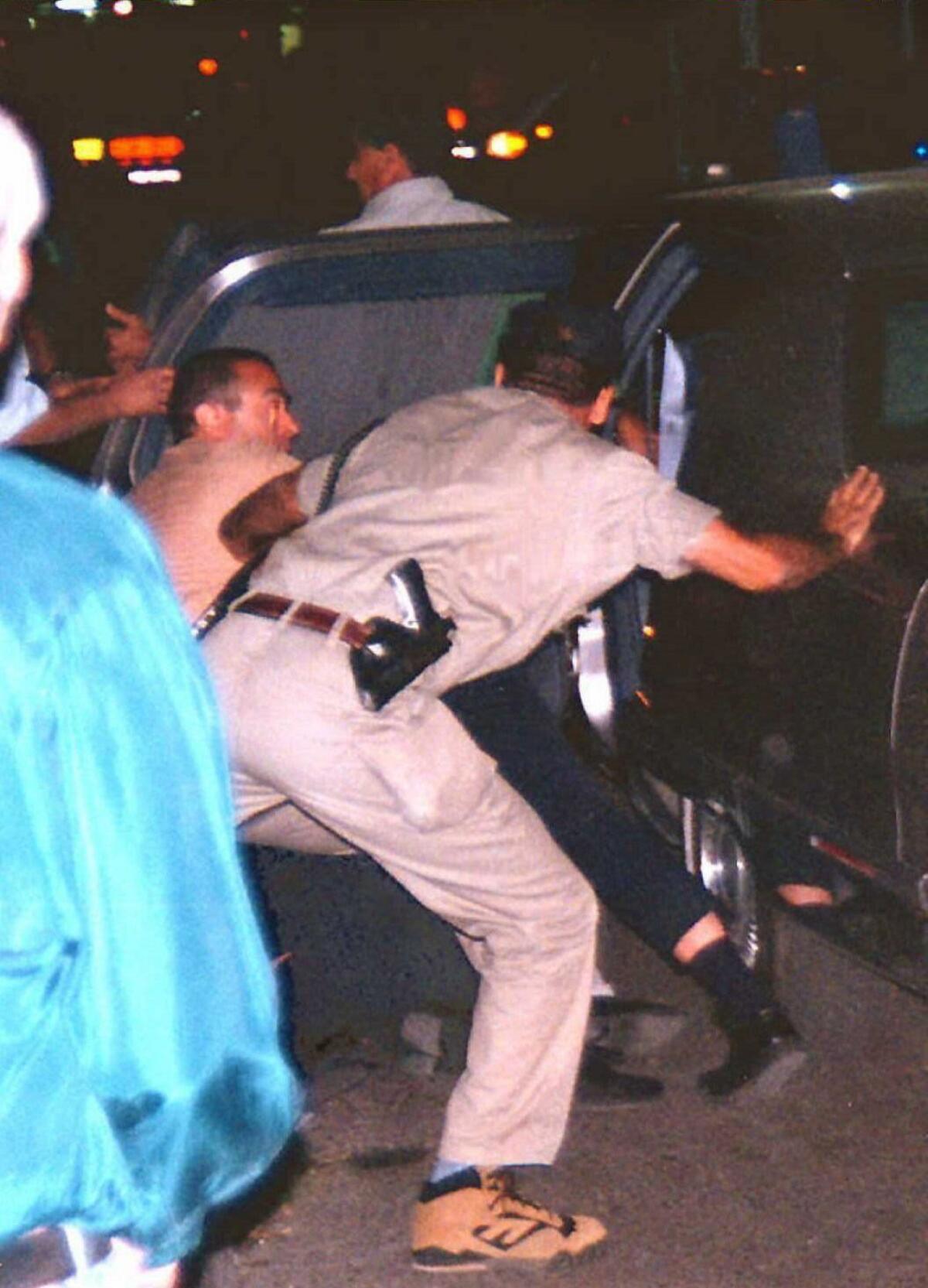

Israeli security personnel pushing Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin into a car after he was shot an assassin in Tel Aviv on Nov. 4, 1995.

Gutman wanted Rabin in the surgery room immediately, where he could cut him open and treat the internal wounds. He and several other doctors wheeled the gurney into a long, fluorescent corridor and began running. Gutman expected the waiting area they passed through to be teeming with people — Rabin’s wife, Leah, his children, his staff members and security team. It was strangely empty.

Leah at that moment was at the headquarters of the intelligence agency Shabak across town. From a phone in one of the rooms, she called her daughter, Dalia. “Your father has been shot,” Leah said. Dalia heard the words but struggled to grasp their meaning. How could it have happened? And what was her mother doing at the Shabak building? “Why aren’t you at the hospital?”

Leah hung up and demanded to be taken to Ichilov.

By the time she got there, Israel Television had interrupted its scheduled program, the movie “Crocodile Dundee II,” to report that the prime minister had been shot and that his condition was unknown. The news brought hundreds of people to the street outside Ichilov, along with journalists and their broadcast vans. Inside, several of Rabin’s Cabinet ministers and staff members had already arrived. The American ambassador, Martin Indyk, was on his way. Eitan Haber, Rabin’s most senior aide, had been at a party in Zahala at the moment of the shooting, along with Ichilov director Gabriel Barbash. At 9:59 p.m., Barbash’s beeper went off with an urgent message to call the hospital. The two men rushed out together.

Then Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin talks with the Associated Press on May 18, 1989 at the Ministry of Defense office, in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Barbash met Leah at the entrance and walked her to a private room near the surgery theater. For the first time, she learned that her husband had been struck by two bullets, that his situation was dire, and that the shooter was not a Palestinian but a Jew. It was too much to absorb. Slowly, the room filled with people.

In operating room 9, other senior doctors had joined Gutman by now, having rushed from their homes, among them Joseph Klausner, the head of Ichilov’s surgery complex. With the anesthesiologists and nurses, as many as 40 hospital staff circled the patient. The rounds that struck the prime minister — the first and third to emerge from Amir’s gun — were hollow points. It occurred to one of the doctors that a protective vest would likely have stopped these particular bullets, with their scooped-out tips. Gutman had removed Rabin’s spleen and cracked open his chest. More than 20 units of blood had been pumped into the prime minister intravenously. When a dose of adrenaline was injected into his heart, Rabin’s vital signs seemed to stabilize. Barbash left the room to report to Leah that the doctors had some hope.

A worker at Israel’s National archives displays the 9mm hollow-point Berreta bullet that was taken out of the body of late prime minister Yitzhak Rabin after his assassination 20 years ago.

In the hallway, Haber immediately swung into action. He spotted a high-ranking Defense Ministry official and told him to begin setting up a makeshift office at the hospital, with phones and fax lines. The prime minister would need to run the affairs of the country from Ichilov while he recuperated.

But Rabin quickly lapsed again. To keep him alive, Gutman reached into his chest cavity and pumped his heart manually, repeating the motion again and again, until he lost track of time. Around the room, the grim realization was setting in that the prime minister could not be saved. Gutman sensed the futility as well, but he couldn’t bring himself to pull away from Rabin’s heart. At 11:02 p.m., 80 minutes after the shooting, Klausner touched him on the back and said it was time to stop. Rabin was dead.

An Israeli schoolboy sets a teddybear on the grave of late Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin at Mount Herzl Cemetery in Jerusalem Tuesday Nov. 7, 1995, a day after the funeral service.

The operating room fell silent. Then some of the surgeons, trauma specialists who had seen terrible ordeals, began to weep. Barbash took several doctors with him to break the news to Leah and the rest of the family. The hallway outside the private room now swarmed with people — members of Rabin’s Cabinet, military officers and security officials. For a moment, the crowd huddled around Leah. Then Barbash led a small group including Leah, Dalia and Dalia’s two children, Noa and Yonatan, to a reception room where Rabin’s body had been wheeled. A white sheet covered everything but his head. To Noa, who was 18 and a private in the army, her grandfather seemed to be smiling slightly. His face had retained its color, but he was cold to the touch. After taking turns standing at Rabin’s bedside, the group filed out.

By this point, masses of people had gathered outside the hospital. From media reports, Israelis had learned that the shooter was a 25-year-old Jewish extremist from Herzliya who studied law at Bar-Ilan. But they still knew little about Rabin’s precise condition. Haber was about to stun the nation. At 11:15 p.m., he walked out of the hospital alone, looking pale and deeply shaken. He stood in front of television cameras and asked for quiet. “The government of Israel announces with shock, with great sorrow and grief, the death of Prime Minister and Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was murdered by an assassin this evening,” he said. At the word “death,” some people erupted in shouts of “No, no!” Others gasped loudly.

The announcement plunged Israel into a haze, a gloomy twilight zone where everything seemed surreal. At a movie house not far from Ichilov, an usher went from theater to theater to convey the news. Audiences filed out in a daze. On Channel One, television’s most distinguished anchor, Haim Yavin, could not bring himself to say the words “Rabin is dead.” Instead, he announced that the prime minister was “no longer among the living.” Yedioth Ahronoth, the country’s largest-selling newspaper, had already laid out its front section for the next day. Its editors now threw out the material and began working on a new edition for what would be a different country in the morning.

The columnist Nahum Barnea, who had covered the peace rally earlier in the evening, sat down and wrote: “Ever since Israel was established people believed, rightly so, in the stability of the regime. Only in Arab countries are leaders assassinated. Only in Arab countries, people who strive for peace pay with their lives.... We were mistaken. We are not immune.”

Dan Ephron is a former Jerusalem bureau chief for Newsweek magazine.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

MORE ON YITZHAK RABIN

What would have happened if Yitzhak Rabin had lived?

20 years ago today, Rabin assassination changed history

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.