Op-Ed: In ruling on Obamacare provision, court didn’t rewrite law — it read it

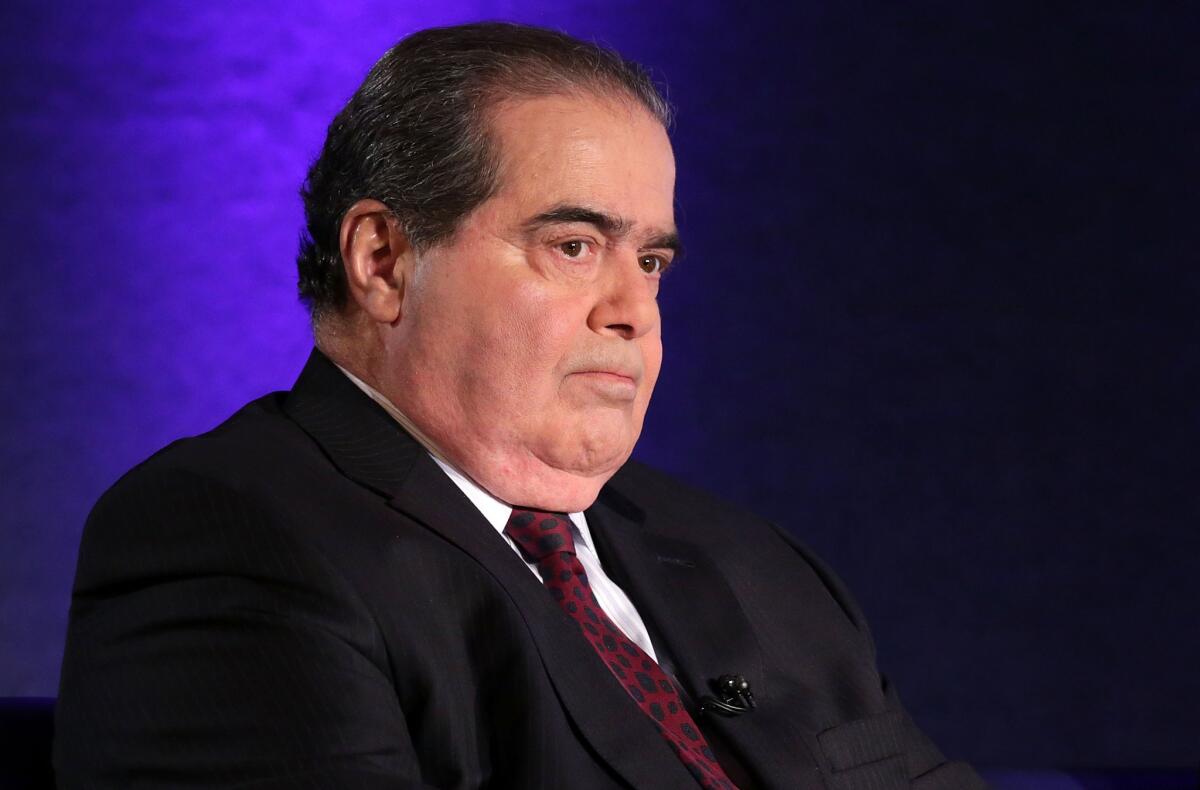

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia at the National Press Club in Washington on April 17, 2014.

The Supreme Court’s decision Thursday in King vs. Burwell is a huge win for supporters of the Affordable Care Act. It’s also a huge win for common sense in statutory interpretation.

President Obama’s signature law invited the states to establish exchanges through which their residents could buy health insurance and, if eligible, access subsidies. In the end, however, only 16 opted to do so. The other 34 states chose to rely on Healthcare.gov, the federally run exchange created on their behalf.

In a highly technical provision, the law sets out a formula for the size of the subsidy, with reference to the cost of a health plan bought through “an Exchange established by the State.”

The plaintiffs, eager to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, seized on this language to argue that subsidies weren’t available to residents of the 34 states that failed to establish their own exchanges. The exchanges in those states weren’t “established by the State,” they said — so no subsidies.

Why would Congress have wanted to withhold subsidies in states that failed to establish their own exchanges? That’s a hard question to answer, given that the whole point of the statute was to expand access to health insurance. But the plaintiffs concocted a story. Maybe Congress really liked state exchanges, they said, and wanted to put pressure on states to set them up. After all, few, if any, states would refuse to create an exchange if it meant the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars to their residents.

The plaintiffs’ position has always reminded me of an old Amelia Bedelia story. When the literal-minded but bighearted housekeeper is told by her employer to weed the garden, she decides to plant a big row of really big weeds. “She said to weed the garden,” insists Amelia Bedelia, “not unweed it.”

When asked why anyone would want more weeds, Amelia Bedelia has to stop and think. “Maybe vegetables get hot just like people,” she says. “They need big weeds to shade them.”

Writing for a six-justice majority, Chief Justice John. G. Roberts Jr. recognized that the plaintiffs’ attempt to explain why Congress would withhold subsidies for residents of some states was every bit as “implausible” — his word — as Amelia Bedelia’s notion that vegetables need shade. In his view, other provisions of the statute demonstrated that Congress meant subsidies to be available nationwide.

The chief justice pointed out, for example, that insurers are required to sell insurance to all comers, no matter how sick. That’s true in every state, not just the states that set up their own exchanges. As the chief justice recognized, however, the combination of this anti-discrimination rule and the loss of subsidies would wreak havoc on the federal exchanges.

The subsidies are substantial, averaging $3,264 a year. Healthy people who couldn’t afford to pay the full sticker price for insurance would drop their coverage, leaving sicker people behind. Insurers would then have to increase their prices to cover the healthcare costs of those sick people, pushing still more healthy people to shed coverage.

In other words, the chief justice wrote, the loss of subsidies would “destabilize the individual insurance market in any State with a Federal exchange, and likely create the very ‘death spirals’ that Congress designed the Act to avoid.”

The chief justice brushed aside the plaintiffs’ contention that Congress meant to threaten the destabilization of state insurance markets to force the states to create exchanges. To the contrary, the law specifically anticipated that some states would decline to set up exchanges by providing for a federally run exchange.

Why read the statute to punish laggard states? As the chief justice wrote, “Congress passed the Affordable Care Act to improve health insurance markets, not to destroy them.”

In a heated dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia took issue with the majority’s willingness to look beyond literal meaning, arguing that the decision “rewrites” the law “under the pretense of interpreting it.”

“Words no longer have meaning,” Scalia wrote, “if an Exchange that is not established by a State is ‘established by the State.’”

That sounds snappy, but Scalia is wrong. He’s the Amelia Bedelia of the Supreme Court, who would transform statutory interpretation into a game of gotcha, where slipshod drafting is an excuse to ignore persuasive clues about what Congress meant to communicate.

Words do still have meaning. It’s just that reading the law as a whole — keeping in mind what it aims to accomplish and how it goes about accomplishing it — is the right way to figure out what those words mean, not blinkered literalism.

Anyone who knows anything about gardening knows that you don’t plant weeds to help vegetables. And anyone who knows anything about how the Affordable Care Act works knows that Congress didn’t intend it to devastate health-insurance markets.

As the chief justice rightly appreciated, the broader statutory context thus confirmed that Congress could not have meant what, taken out of context, it seems to have said. That’s not rewriting the law. That’s reading it.

Nicholas Bagley is an assistant professor of law at the University of Michigan.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.