Column: Election forecasting in the age of Trump

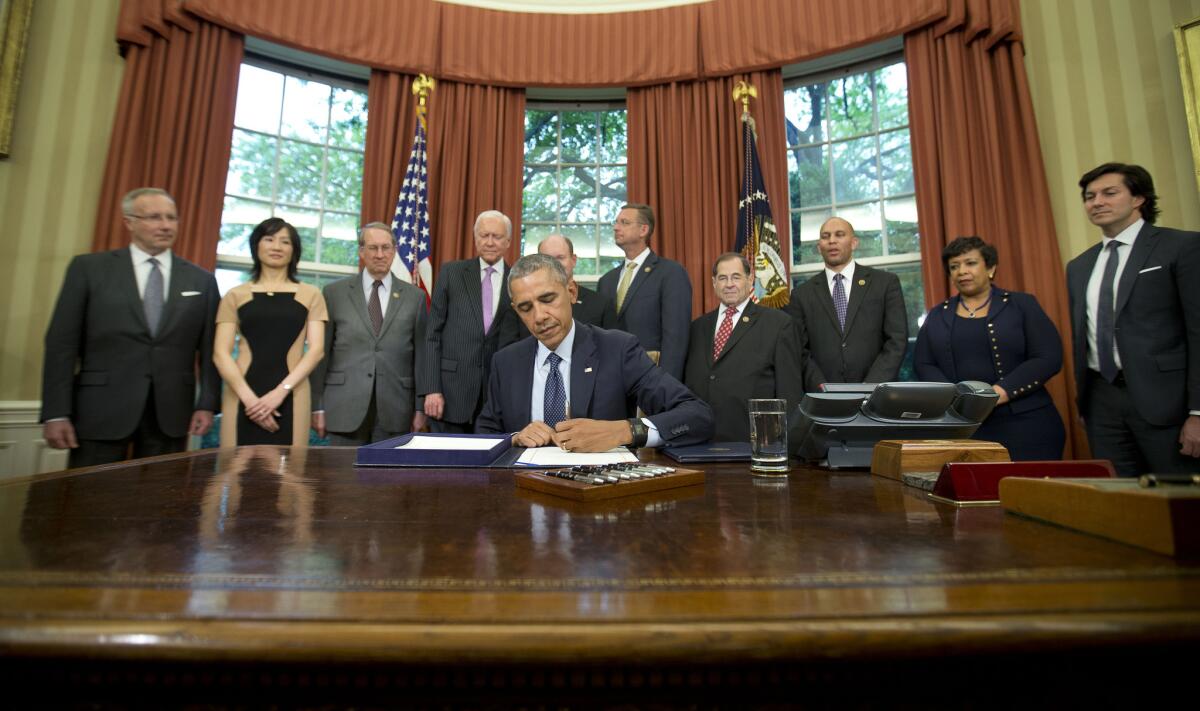

It’s hard for one party to keep the White House for a third term, as Hillary Clinton is trying to do. Above, President Barack Obama at work in the Oval Office on May 11.

Ray Fair of Yale University says that if his election forecasting model is correct, the Republican nominee is likely to win the presidency by a convincing margin. John Sides of George Washington University agrees; the “fundamentals,” he says, give the Republican about a 60% chance of winning. Alan Abramowitz of Emory University gives Republicans a solid shot at the White House too; his model gives the GOP the edge — but in “a very close election.”

But thanks to Donald Trump, their carefully honed forecasting models may have lost their predictive magic — a possibility the professors themselves acknowledge.

“This time may be different,” Abramowitz told me last week.

For decades, political scientists and economists have concocted statistical models to try to predict presidential elections even before the actual campaigns were under way. Their aim wasn’t merely to pull off the parlor trick of predicting a winner; more important (to them, at least) was figuring out what makes voters tick. Their underlying theory was that most voters’ behavior stems from a combination of fundamental factors and not from anything the candidates say or do.

Abramowitz’s model, for example, uses three factors: economic growth, the current president’s popularity, and how long the incumbent party has held the White House.

Starting with that last item: It’s hard for one party to keep the White House for a third term, as Hillary Clinton is trying to do. It’s only been done once in the last half century, when George H.W. Bush succeeded the popular Ronald Reagan in 1988. Abramowitz calls this the “time for a change” factor, and it puts the presumptive Democratic nominee at a significant disadvantage.

Right now, the economic fundamentals don’t look good for Clinton either. Most forecasts suggest that growth will remain well below 3% all year, a sluggish rate that favors the party out of power.

Obama, on the other hand, is actually helping Clinton’s chances; his job approval rating in the Gallup Poll has averaged about 50% over the last six months, just high enough to give her a chance of winning.

Most forecasts suggest that growth will remain well below 3% all year, a sluggish rate that favors the party out of [the White House].

Add all three factors together, and the result is “close to 50-50, maybe a little below” for the Democrat, Abramowitz said. “So based on the fundamentals, you would expect this to be a very close election.”

Now add a new factor: Trump.

A model like Abramowitz’s “doesn’t take into account attributes of the candidates. It captures arguably the most important things, but not everything,” Sides told me.

“These forecasting models assume that you have mainstream candidates who will unify each party,” Abramowitz conceded. “Trump doesn’t fit that pattern. He’s off the charts. And it’s very hard to predict how that’s going to play out.”

Despite the chilly indifference of the forecasting models, he noted, candidates and their campaigns do matter. In 1972, Democrat George McGovern did worse than the models would have predicted, presumably because many voters saw him as too far to the left. In 1988, Michael Dukakis also did worse than the models predicted, “probably because he had the worst campaign in recent memory,” Abramowitz said.

So even though the forecasting models say this should be a Republican year, the polls don’t agree. An average of recent polls puts Clinton ahead of Trump, 47% to 42%. The Iowa Electronic Market, one of several “prediction markets” that crowdsource forecasting, projects that Clinton will win 58% of the popular vote. And the conventional wisdom among pundits — not that we’ve been particularly prescient of late—is that Clinton could win in a landslide.

Trump isn’t just disrupting the Republican Party, he’s disrupting political science too.

One of the potential problems with the models in an election like this one is that they assume voters aren’t really paying much attention to politics.

The models — and their underlying theories of voting behavior — rest heavily on how voters feel about the economy on Election Day. In a sense, they suggest that voters decide many elections on the basis of James Carville’s slogan from the 1992 campaign: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

That’s not entirely rational.

As political scientists Christopher M. Achen and Larry M. Bartels point out in their recent book, “Democracy for Realists,” voters who choose based on the economy are often holding an incumbent president and his party responsible for events beyond his control. (Besides, they note, economic voters choose based on how the economy is doing in the months before Election Day, not during a president’s entire term.)

“The result of this kind of voter behavior is that election outcomes are in an important sense random,” they write – a matter of whether a given president has been lucky or not. “Economic voting may be little more than a high stakes game of musical chairs.”

Love him or loathe him, Trump may have changed the equation, forcing voters to think more about whom they want in charge instead of letting GDP growth rates effectively determine their preference. He’s made voting important again.

Twitter: @DoyleMcManus

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

MORE FROM OPINION

I loved Uber as a passenger. Then I started working as a driver

If California legalizes marijuana, consumption will likely increase. But is that a bad thing?

Chicken workers in diapers — more evidence of the high cost of cheap meat

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.