The eternal disputes of the Dead Sea Scrolls

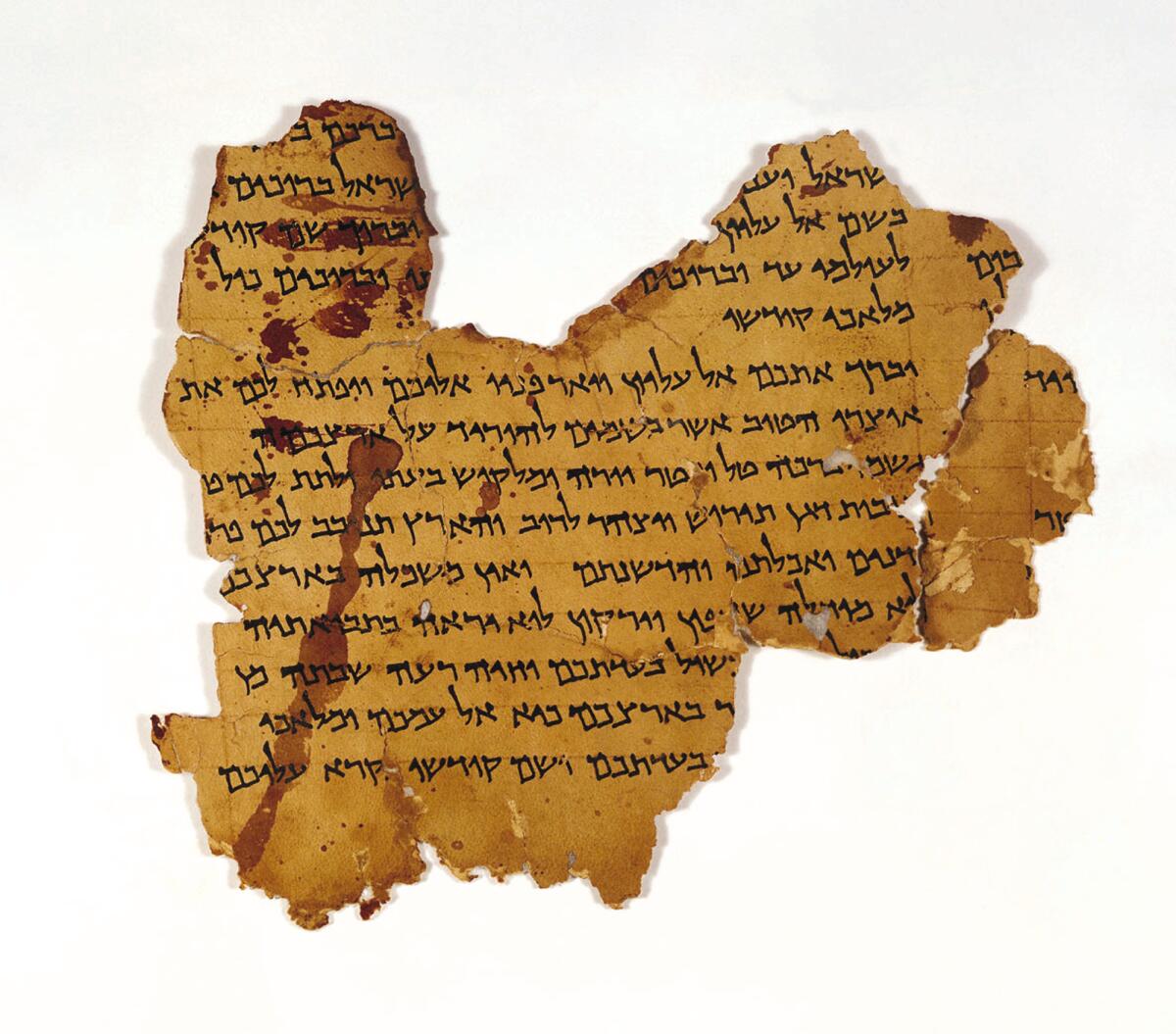

In June 1954, a small advertisement ran in the Wall Street Journal: “Biblical manuscripts dating back to at least 200 BC are for sale.” The commercial offering was the start of a long and controversial path for the Dead Sea Scrolls, a cache of fragmentary writings in Hebrew and Aramaic (with a few in Greek) that were found in caves near the Dead Sea between 1947 and 1956.

The ancient documents include early copies of almost every book of the Hebrew Bible and have been called, justifiably, the greatest archaeological discovery of the 20th century. But that is one of the few things scholars have agreed on.

The first controversy followed fast on the scrolls’ discovery in the late 1940s, in what is now known as the West Bank. The region was in turmoil in the wake of the United Nations vote establishing a partition plan to create independent Jewish and Palestinian states.

The manuscripts offered in the Wall Street Journal had been brought to the United States by a Syrian archbishop, who didn’t want the scrolls to end up in Israeli hands. But it turned out that the purchaser, unbeknown to the sellers, was acting on behalf of the state of Israel, and so the first scrolls discovered ended up in Israel and can still be seen in the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem.

The great trove of texts found after Israeli independence, however, was under Jordanian control, and no Jewish scholars were allowed on the official team of editors who had exclusive access to the manuscripts. After the 1967 war, all the scrolls came under Israeli control, but ownership is disputed to this day.

Controversy erupted anew during the 1950s when John Allegro, a maverick member of the editorial team, claimed in a British radio broadcast that a Jewish sectarian leader, known as the Teacher of Righteousness, had anticipated Jesus Christ in uncanny ways. According to Allegro, the teacher was crucified and his followers “took down the broken body of their Master to stand guard over it until Judgment Day,” when he would rise again. The other editors protested that they found nothing of the sort in the scrolls. Allegro later fully discredited himself by publishing “The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross,” in which he argued that Christianity was a fertility cult involving sacred mushrooms.

In the 1980s, scholars grew impatient with the long delay in publishing the scrolls, which meant that access to them was severely restricted. That controversy came to a head in 1991 when the editor in chief, John Strugnell, was forced to resign after he was quoted in an Israeli newspaper as saying that Judaism was a horrible religion that ought not to exist. Strugnell, an alcoholic who also suffered from bipolar disorder, was not of sound mind when he gave the interview. He had a good record of working with Israeli scholars and was the first to include some of them on the editorial team, but his position was obviously untenable.

The publication of the scrolls, however, remained a contentious issue, even when access to them was no longer restricted.

The unauthorized publication of an important text called 4QMMT (“Some of the Works of the Law”) by Hershel Shanks in Biblical Archaeology Review became the subject of a lawsuit by Elisha Qimron, one of the editors to whom the text had been assigned. An Israeli court ruled against Shanks, and the trial cost him more than $100,000.

The most recent uproar about the scrolls involved Raphael Golb, son of University of Chicago professor Norman Golb. The younger Golb created more than 80 Internet aliases between 2006 and 2009 to advance his father’s views about the scrolls, and to give the impression that a large number of people were concerned that the elder Golb was not being treated fairly.

More ominously, he sent out emails in the name of a leading scrolls scholar, Lawrence Schiffman, then of New York University and now of Yeshiva University, in which Schiffman supposedly confessed to plagiarizing the elder Golb. Raphael Golb was convicted in a New York court in November 2010 on charges that included identity theft and forgery, and his conviction was affirmed on appeal this year.

So why have these ancient artifacts aroused such passions? To be sure, the most bitter controversies have been fueled by outsize egos and pursuit of publicity. But other discoveries, such as the Coptic texts from Nag Hammadi, have stirred no comparable passions. What makes the scrolls different is that they are the only primary texts we have from Judea that date to about the time of the birth of Christianity and just before the rise of rabbinical Judaism. Consequently, they are precious evidence of the nature of Judaism at a time of enormous consequence for Western history. Scholars who control the interpretation of the scrolls can potentially have a great impact on the understanding of Judaism and Christianity, and it is the lure of such influence on the understanding of Western history that has made the scrolls a battleground nonpareil of academic controversy.

In fact, the impact of the scrolls is somewhat less than is sometimes claimed, but it is considerable nonetheless. They shed light on the Scriptures that were revered in the time of Jesus; they provide numerous parallels in detail to the New Testament; they show that a concern for exact interpretation of the law, which is characteristic of rabbinical literature, was already in place around the turn of the era; and they also show that there was considerable variety in the Judaism of the time. Nothing in the scrolls either validates or discredits Christianity or Judaism as they later evolved, but the scrolls are an invaluable source of information about a crucial juncture in the development of Western religion.

John J. Collins is a professor at Yale Divinity School and the author of “The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Biography.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.