From the Archives: The Story Behind the Story: How The Times decided to publish the Schwarzenegger story

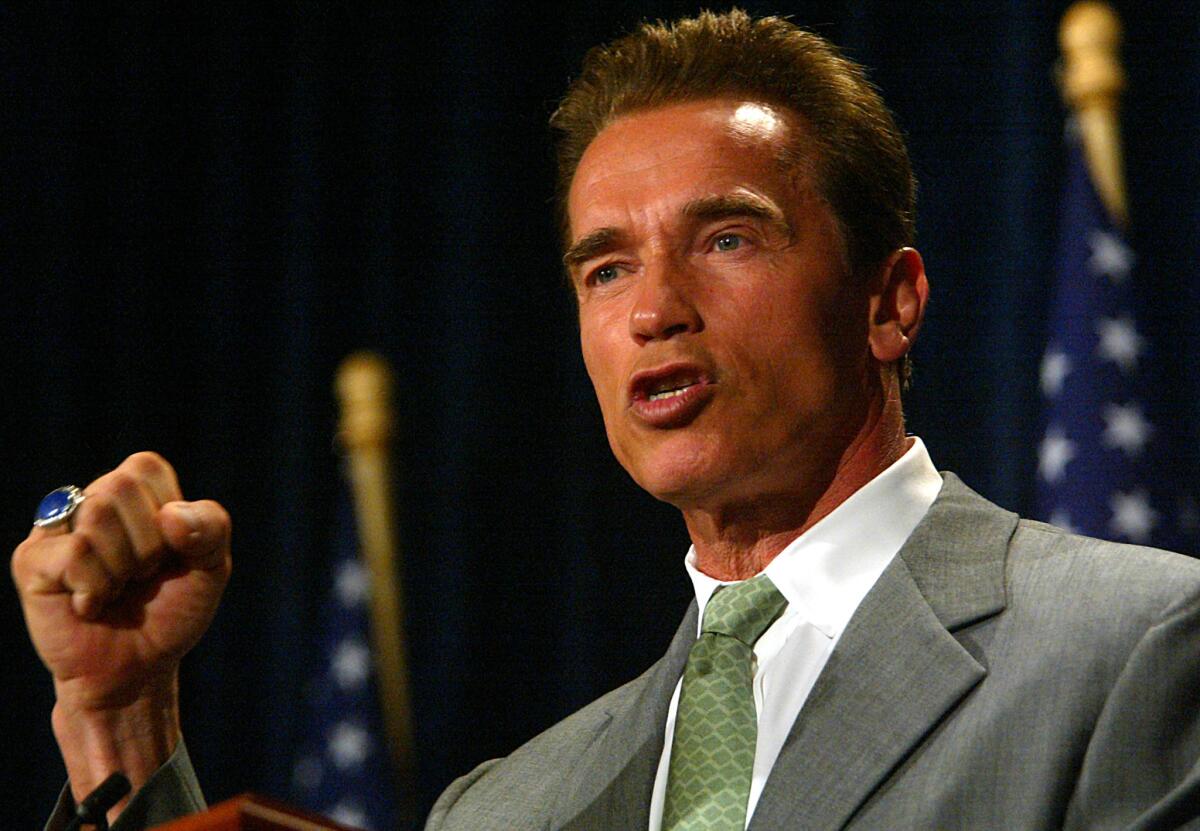

Arnold Schwarzenegger holds his first press conference as governor–elect of California at the Century Plaza Hotel on Oct. 8, 2003.

The volcanic passions of the recall are largely spent, though we’ll no doubt be feeling their effects for many years. Today, on this Sunday of relative calm, I’d like to tell you how the Los Angeles Times decided to publish the stories of 16 women who said they had been sexually mistreated and humiliated by Arnold Schwarzenegger.

I’ll also tell you why we published the first of those articles a mere five days before voters went to the polls, a decision that has prompted an outpouring of campaign denunciations, talk-show rants and blistering emails.

Critics have accused the newspaper of malice toward Republicans and of collaboration with Gray Davis and the Democrats. It has been suggested that we cynically concealed the completed story for weeks before detonating it as a last-minute bomb. Some used the term “October surprise.”

I’ll begin this accounting with a bit of background: One of our goals is to do more investigative reporting. At the risk of offending still more readers, I’ll say that if you’re put off by investigative reporting, this probably won’t be the right newspaper for you in the years to come.

Investigative skills were needed when Schwarzenegger announced for governor on Aug. 6. For years, he’d had a reputation in Hollywood as a man who treated women crassly. The gossip about him reached a peak after Premiere magazine published an article in March 2001 titled “Arnold the Barbarian.”

Because Schwarzenegger had a chance of becoming our next governor, we decided on the day he entered the race to see whether this reputation was warranted. The examination was part of a broader look at all the leading candidates, covering their life histories, their stands on the issues, their personalities and their characters.

We assigned the task of investigating Schwarzenegger’s reputation to two veteran reporters: Robert Welkos, who has covered Hollywood for half of his 25 years on the paper, and Gary Cohn, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1998 for investigative reporting at the Baltimore Sun.

They were joined by Carla Hall, a former Washington Post reporter who has covered news and features here for a decade, and many others, most notably Tracy Weber and Megan Garvey.

The undertaking was not easy. How do you find women who say they have been mistreated? How do you persuade them to talk? How do you determine whether they’re telling the truth?

The reporters started by asking the paper’s many Hollywood sources for names of possible victims. The names of other people who might have knowledge of Schwarzenegger’s behavior were gleaned from the credits of his films.

Then the reporters began trying to find the women.

It is hard to overstate the amount of wasted time such work entails. People move from one town to another. Their last names change.

When strangers show up at their doors, they are suspicious.

When the subject of the story is mentioned, they say they’re afraid of losing their jobs. They contemplate sharing their private humiliation with millions of readers, and their stomachs ache.

They say they’ll think things over and call back. They don’t.

Friends counsel them not to get involved.

When a woman finally does agree to tell her story, it must be verified.

Do details change from one interview to another? What do databases show about her background? Does she have a criminal record? Has she been sued?

Can she prove that she actually was employed where she says she was?

And where was Schwarzenegger at the time?

Will she allow her name to be used? If not, how about her occupation? Such discussions drag on and on.

When it’s clear that her story holds together, the search for corroborating witnesses begins. This, again, requires database searches, phone calls, home visits and discussions over how much the paper can publish without putting a job at risk.

When all the reporting is done, her story still needs to be written. And then it must be integrated into a larger story including other women.

It was a daunting feat to get all this accomplished during the 62 days of Schwarzenegger’s campaign, a year less time than we’d have to cover a normal gubernatorial race.

A critic has claimed that The Times actually finished the Schwarzenegger story long before the election.

“They had the story done two weeks ago,” this critic said on national television. “And they should have published it when it was ready to go....”

The statement was, as the old editor’s saying goes, “a good story, if true.”

From our files, here is what really happened: On Sept. 15, a federal court ordered the election postponed. (The order was later reversed.) The next day at 1:35 p.m., I sent the following email to the reporters working on the story:

“Yesterday, when we discussed your stories, I was concerned about the brief time frame we have for getting them reported and into the paper. The subsequent decision to postpone the election shouldn’t be seen as a reason to slow down.

“The information you’re seeking, if verified, ought to be known by the voters before election day, not after. It’s quite possible that the election will be held as originally scheduled, so please press ahead at full speed.”

That was 16 days before the story was published. Does it sound as if we were sitting on it?

This critic’s accusation was among several lulus cranked out by local journalists.

It was also written, for example, that Davis was the puppeteer behind The Times’ stories. Fact: None of the information in The Times’ stories came from the Davis camp, as we said in the articles when we published them.

It was written that high Democratic officials were kept apprised of the newspaper’s probe, step by step. Fact: No Democratic officials were apprised. Because the paper was interviewing many sources, the existence of the investigation was widely known, but the details were not. The Davis people may have learned that the investigation was underway from websites, which mentioned rumors about it repeatedly.

It was written that the paper failed to follow up on reports that Davis had mistreated women in his office. Fact: Virginia Ellis, a recent Pulitzer Prize finalist, and other Times reporters investigated this twice. Their finding both times: The discernible facts didn’t support a story.

It was written....

Well, you get the idea.

In days past, such misleading stories tended to make a brief splash and then sink into richly deserved oblivion, but we’re living in changing times.

Today, if a story has potential to stir resentment among large numbers of people, it is seized like gold by the talk shows. Whether true or false, it is cynically packaged as the inside story “they” don’t want you to know.

Early in its electronic life cycle, such a story bounces around the talk shows and the Internet, often presented breathlessly as a revelation. Later, intoned on TV by people in dark suits, it acquires the solemnity of established truth.

The electronic revolution has brought us many blessings, but it has also blindsided us with a tidal wave of pornography. In similar fashion, we are now getting a faceful of rotten journalism — journalistic pornography, actually — in which ratings are everything and truth is nothing.

As the Schwarzenegger story came into focus, these were our choices:

* Publish it late in the campaign. Given the passions of the election, this would touch off an outcry against the newspaper. We had no illusion that it would be warmly received.

* Hold it and publish after the election. This would prompt anger among citizens who expect the newspaper to treat them like adults and give them all the information it has before they cast their votes.

* Never publish it. This could be justified only if the story were untrue or insignificant.

We, of course, chose the first option. Regrets? Not one.

When the story was published, Schwarzenegger admitted that he had “behaved badly” in the past and offered a general apology to any women he had offended. At another point, he said, “I have never grabbed anyone and pulled up their shirt and grabbed their breasts and stuff like that.” But when asked whether he was denying all the stories about grabbing, he said, “No, not all.” At still another point, he questioned the credibility of some of the women.

But the facts in The Times’ stories have not been seriously challenged.

The merit of an investigative story can be judged, to an extent, by what happens in its aftermath. In this case, the initial story reported that six women said they’d been sexually mistreated by Schwarzenegger. Two of the women were quoted by name. Four declined to be named, three fearing that they would be blackballed by the movie industry and one concerned that she would be publicly ridiculed.

Personally, I knew the stories were solid as Gibraltar, but I was worried that readers might see the evidence as thin.

In any case, it didn’t take long for it to thicken. Soon after our first story, additional women began to come forward. Two appeared at press conferences to describe their ordeals with Schwarzenegger, and another did so at a political demonstration. Still more revealed their stories to The Times.

By election day, the total was 16, of whom 11 were named. Details of their stories varied, but there were common themes, including a feeling of deep helplessness and lasting humiliation. Knowing the anguish they had expressed to our reporters, I admired their courage.

Among those employees whose misfortune it is to answer the phones at The Times, there is a consensus that our angriest critics haven’t actually read the stories. Instead, they’ve heard about them secondhand.

If you would like to read them, they are posted on our website: www.latimes.com/recall.

I believe they’ll strike you as rigorously factual and even in tone. They’re also certain to strike you as vulgar, perhaps even obscene. My wife informed me that I’d strayed far over the line in publishing one of the anecdotes.

But such is the behavior at the heart of the issue.

Are the stories significant? Some think they starkly illuminate the character of a man who has been elected to the highest office in California. Some don’t. Our role is to serve citizens of varying views by examining the behavior and the policies of political leaders and publishing our findings.

And when we publish, we do it in a timely fashion. Better, I say, to be surprised by your newspaper in October than to learn in November that your newspaper has betrayed you by withholding the truth.

John S. Carroll is the editor of the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.