From the Archives: Making history: a 2009 interview with California historian Kevin Starr

Editor’s note: This 2009 interview with Kevin Starr was published in The Times’ Opinion section. Starr died Saturday, Jan. 14, 2017, at 76.

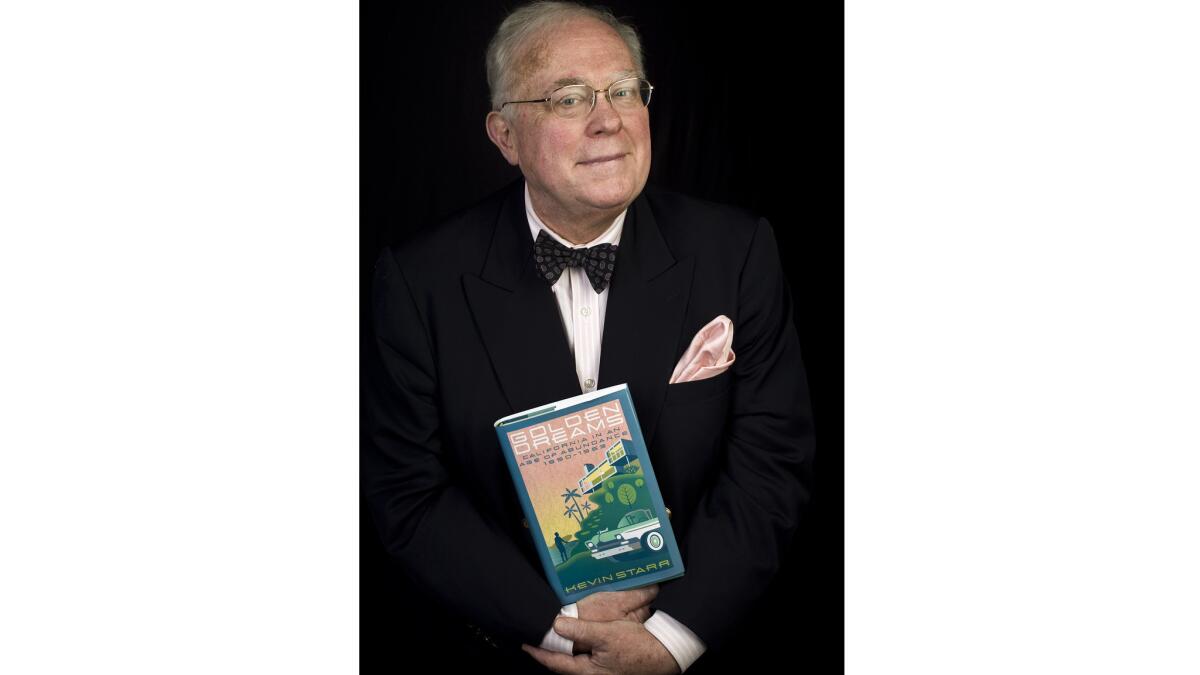

I made the acquaintance of Kevin Starr’s books long before I made the acquaintance of Kevin Starr. “Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963,” the eighth volume in his serial love letter to California, is arriving in bookstores this weekend.

I have them all. When you fall in love, you try to find out all you can about the object of your affection. Once I fell for California, Starr’s history books, with their cinematic and journalistic sweep, ensnared me in a way that no monograph, no memoir could do. Clear-eyed but ultimately hopeful, they’ve sold well, but, as he says, “People aren’t going to the beach with an Oxford University Press book.”

Starr and I have shared a table at a book group for about 10 years. I know that he’s been the state’s librarian, where he also coordinated the search for a design for this state’s official two-bit coin. I know he’s been a history professor for years, currently at USC. I know he’s got a memory like some California-specific Google software. But not until I interviewed him did I know he lived, for a time, on welfare with his mother and brother in San Francisco’s Potrero Hill housing projects -- the same place O.J. Simpson grew up. I didn’t know he’s trying his hand at a screen treatment. And though I know he plays pool, I didn’t know he learned how in a Ukiah orphanage.

You grew up in an orphanage?

My mother had a nervous breakdown, and my parents separated. Roman Catholic Social Services put us [Starr and his brother] in an orphanage for five years. I loved the place. It was a tremendous education, great nurturing. There was a great pool table, a great library, a camp up in the mountains. My experience was very different from some of these horror stories you hear.

What’s your personal history with history?

My great-grandfather came to San Francisco in the early 1850s. My other great-grandfather came in the early 1870s. My grandmother would tell me about going to the Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915. She had a banana plant she bought there -- 30 years later, it [was] still growing. She told me about the [1906] fire and earthquake. So from her I absorbed this tremendous sense of the San Francisco story.

You’ve said that in some ways you didn’t discover California until you got to graduate school at Harvard.

This Yankee institution had a tremendous sense of the history of the West. I started to browse on the fourth floor of the Widener Library in the California section, and suddenly it dawned on me. I thought, “There’s all kinds of wonderful books on California, but they don’t seem to have the point of view we’re encouraged to look at — the social drama of the imagination.” So I started the first volume, writing it for my thesis.

So it was California, the untold dream?

I’ve always tried to write California history as American history. The paradox is that New England history is by definition national history, Mid-Atlantic history is national history. We’re still suffering from that.

Did you have a hard time initially getting others to take California seriously?

Oh, absolutely. I think we still have that.

As a San Franciscan, did it kill you to have to say nice things about L.A.?

I came down here on vacation in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, and I fell in love with Southern California. I think that divide has been out of date since the 1960s. A tremendous anxiety overcame San Francisco in the early 1920s when Los Angeles became the most populous city in the state. Cities tend to get twinned: Boston and New York, Kyoto and Tokyo. One is more open, assimilative, growing, exuberant; the other becomes more self-reflective. By 1855 (eight years after the city became Americanized), San Francisco is publishing “The Annals of San Francisco,” an 800-page book.

Sheila, your wife — to whom you dedicate this book with “we met in this time and began our life together” — has said you tell history like you’re holding forth at the bar at the Bohemian Club.

I like narrative, and I ultimately am in love with the men and women I write about, most of them. My editor eliminated 350 to 400 pages. But she also suggested that narrative history takes room.

How do you keep all your research organized?

They talk about San Francisco sourdough bread, that the yeast in the bread is alive since 1849. I started a bibliography of California that I have kept alive for over 45 years, every time I come across a reference. I’ll read something by you, and that’s a reference.

It seems like you keep most of it in your head too.

The Irish didn’t read and write for a couple of thousand years, and I think we developed good memories and recall. We have a sense of the revelatory detail. I look for them.

It’s a funny thing — when I go “blah, blah, blah” argumentatively, that’s when my editor cuts me the most. One reviewer said, “Oh, he’s got great description, great narrative, but he doesn’t give us the great explanation.” I try to let the reader get his own explanation. That becomes part of the discourse the book engenders. But if you tie yourself up with a big explanation, it’s dated in six months.

Is there a part of this book you especially liked doing?

For the chapter on my own generation, I went through hundreds and hundreds of yearbooks, from the late ‘40s until ‘63, ’64. It’s not scientific research; it’s very impressionistic. I always thought the women of my age group got short shrift because the women’s liberation movement came slightly after. You look at the yearbooks and you see the future homemakers of America — hurray for that — but you also see them in the engineers club. You see minority kids as student body presidents at a time when everyone was supposed to be terminally racist. Yearbooks are genres; they’re also folk art, folk documentation.

If we had our own currency in California, whose faces should be on it?

Josiah Royce, the great Grass Valley-born philosopher who first formulated what California would be about. Isadora Duncan — her grandparents came here in a covered wagon. The young Native American woman stranded on San Nicolas Island, the “Island of the Blue Dolphins” story. Gov. [Jose] Figueroa, who died trying to redistribute land to the Native Americans. There’s all kinds of wonderful people. If we had living people, I’d put Joan Didion there.

And John Muir?

John Muir’s on our California quarter. [Gov. Schwarzenegger] chose the John Muir/Half Dome [design] and put the condor in. Then Maria Shriver said, “You’ve got to put some redwoods off to the side.” They liked that back at the mint. It balanced the coin. The mint’s very strict. If you’re going to make a couple of million quarters, they’ve got to be able to stack!

A Times reviewer once wrote that there are few victims in your histories. Are there victims in California history?

You mean permanent victims? There are people who were victim-ized, but they didn’t stay permanent victims. Native Americans were enslaved; they were hunted down like vermin. That’s pretty intense victimization. Ishi does not become a victim. He was victim-ized, but he becomes triumphant.

If by victim you mean someone who’s permanently deformed, forever having their humanity marred — I don’t believe it. In fact, I believe that’s a form of dangerous stereotyping, to ascribe permanent victimhood to any group. Groups have suffered powerful injustice, and yet when you say that, you also have to say that they triumphed, that they prevailed. I don’t reverberate to victimhood, probably because of my own life. I refused to become a victim myself, so it’s not one of my big stories.

So in a way, your books have a personal resonance.

There you have it. This is a projection of interior landscape as much as if I wrote a novel.

From a historian’s viewpoint, is California manageable now?

In our public life, we’re on the verge of being a failed state, and no state has failed in the history of this country. In Sacramento, this dysfunction, this end of politics — the people in my book, the good old boys and girls, they may have stayed up late at the Hotel Senator and drunk Maker’s Mark, and some of them may have consorted with loose women occasionally, but when it came down to it, they understood the art of the deal, they understood politics as the art of the possible.

I am just appalled by [what’s going on now]. I think we’re playing a game of brinkmanship that’s very dangerous. Why is it 50 or 60 years ago we had the capacity to lay down the physical, psychological, cultural, public infrastructure of a global mega-state, and today we are on the verge of being Honduras?

You still dress like Harvard, not Hermosa Beach.

When I was a boy, I delivered newspapers to Brooks Brothers. I looked in the windows and saw those things. At Harvard, when my professors came to class, it was showtime. So possibly that was it.

Could you ever live anywhere else?

In terms of everyday real life, I prefer being here. I belong to the Harvard Club of New York and always love to go there and have a Manhattan in Manhattan.

We need a drink named after California.

Some people say the Martini was invented in Martinez.

I think that’s a stretch. What are the canards about California that you hate most?

That everybody’s just sitting around being sloppy and a slacker.

Seventy percent of the population is between San Diego and Marin County, and 70 miles from the coast. That’s an extraordinarily prized and privileged Riviera of universities, homes, etc. It’s got its problems, and it’s not perfect; there’s lots of poverty too.

It’s highly competitive to be here. People don’t come to California to drop out anymore. It’s a very striving place.

You’ve got a screenplay in the works?

Screen treatment. How can you survive in L.A. if you didn’t have a screen treatment? “The Octopus,” by Frank Norris, is the single greatest novel, well, running neck and neck with “The Grapes of Wrath,” ever written about California. The themes of industrialism and minorities and women’s rights and the environment — anyway, it’s fun to have done it.

Is this the last “Dream” volume?

I don’t know. My God, I’m 68. I’ve got this [other] beautiful book about Catholic culture coming to a Protestant nation, and I’ll get criticized because I’m emphasizing how nice the Protestants were to us! Someone else will have to write the ‘60s, although I can give them the title: That would be “Smoking the Dream.”

This interview was edited and excerpted from a longer taped transcript.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.