Editorial: Zinke’s plan for shrinking national monuments belongs in the recycling bin

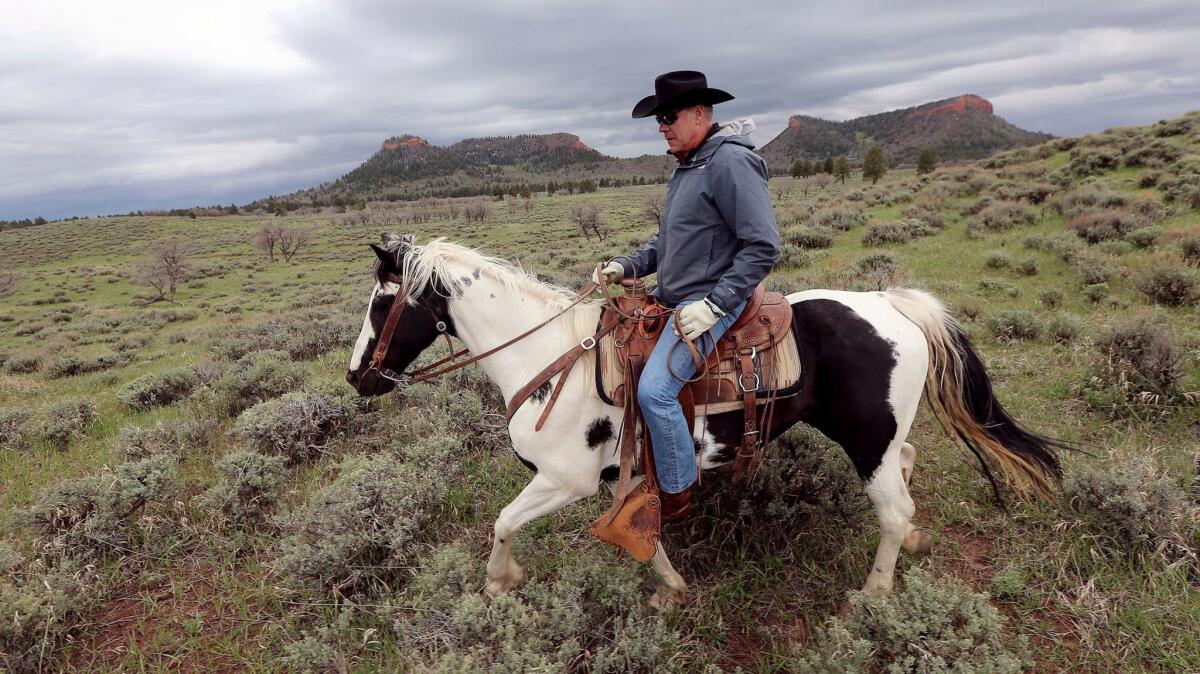

Oooh, the suspense. Thursday was Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s deadline for submitting recommendations to President Trump about what to do with more than two dozen national monuments — encompassing 553 million acres of protected public land and water, much of it environmentally sensitive. Zinke has indeed presented his plan, but neither he nor the White House has bothered to tell the public — you know, the people who own the land — what they have in mind.

There’s obviously reason to be concerned. Zinke’s secret proposals were made in response to Trump’s order in April for a sweeping review of more than two dozen national monuments that were created or expanded under the Antiquities Act of 1906. At that time, Trump said that his objective was to end “another egregious use of federal power” that left millions of acres of land and water “locked up” by the government.

“We’re going to free it up, which is what should have happened in the first place,” Trump said. “And tremendously positive things are going to happen on that incredible land, the likes of which there is nothing more beautiful anywhere in the world.”

But given what we know, it seems likely that Zinke’s process has had less to do with the kind of contemplative weighing of interests that led to the monuments’ creation in the first place than with appeasing conservative politicians and private industries who want the federal government to turn over land to the states so that they can open it to mining and other exploitative uses. Among other things, opening more federal land to oil and gas drilling and coal mining dovetails with President Trump’s ill-advised ambition of vastly increasing production of climate-changing fossil fuels.

The national monuments in question were not created on whims.

Zinke’s two-page report summary, which the administration did release Thursday, makes it clear that his recommendations are based on second-guessing the decisions of prior administrations that he accuses of overstepping their authority to set aside land for special protections. “Adherence to the Act’s definition of an ‘object’ and ‘smallest area compatible’ clause on some monuments were either arbitrary or likely politically motivated or boundaries could not be supported by science or reasons of practical resource management.” The reference to “science” seems almost laughable from an administration that doesn’t even acknowledge the connection between human activity and global warming.

What should happen now is that the president should make Zinke’s report public, and then, assuming it cuts back protections for important, sensitive, majestic, historic, one-of-a-kind areas of vast open space, throw it in the recycling bin.

In fact, there are strong arguments to be made — and, undoubtedly, lawsuits to be filed — over whether the president even has the authority to alter national monuments once they have been designated. The Antiquities Act establishes the power to create them, giving them near national-park-like protections if they contain objects or attributes at risk of damage. But the act makes no mention of a process for rescinding or altering them. It’s true that presidents have altered monuments nearly 20 times in the past, but only one of those changes was significant, and none have been challenged in court. Environmental advocates argue that in the Federal Land Management and Policy Act of 1976, Congress further asserted its power to amend national monuments, further suggesting that the president can create, but he can’t take away.

The national monuments in question were not created on whims. In the case of Bears Ears in Utah, one of President Obama’s last designations, the process took years. Pro-development forces in Utah wanted to preserve some of the nearly 1.4 million acres of federal land for mining, but after reviewing the competing interests — native tribes consider much of it to be sacred, and environmentalists and the outdoor recreation industry strongly urged its preservation — the government decided to protect the land. So it should be. In fact, 90% of the roughly 2.3 million public comments in the Zinke review of the more than two dozen sites urged the government to keep protections of existing monuments in place.

For more than a century, the federal government has recognized the importance of preserving and protecting extraordinary land — the Death Valley and Grand Canyon national parks were converted from national monuments. Now, at the urging of drilling and mining interests, the Trump administration seems to think that the protection process is an abuse of federal power. No, it’s not. But undercutting these protections to benefit private profiteers would be. We’ve said it before and we say it again: Leave the national monuments alone.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.