Editorial: Making the L.A. County Board of Supervisors more politically partisan isn’t the reform we need

Almost every year, Sacramento lawmakers introduce bills to change something or other about the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, and usually for good reason.

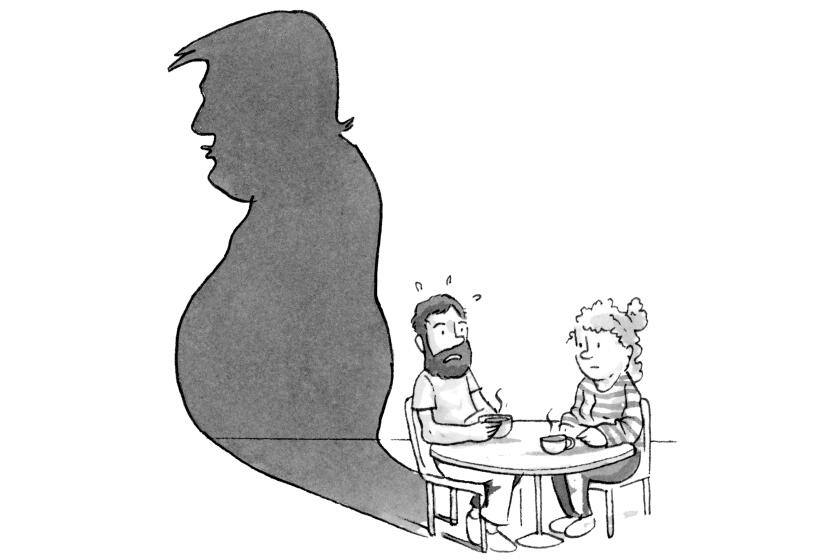

The five-person structure that works well enough in a county like, say, Sierra, with its 3,000 residents, is hopelessly inadequate to represent L.A. County’s 10 million people. Similarly, a government without an elected chief executive is odd yet workable in running a medium-sized county like Sonoma, with its $1.6 billion budget, but out of its depth in L.A. County, with its $28 billion spending plan, its 36 departments and its 100,000-person workforce. Los Angeles County is essentially a state without a governor or, if you prefer, with a five-headed governor with no oversight but itself. Meanwhile, the makeup of the board no longer matches the county’s changed demographics. Nearly half the county’s residents are Latino, but only one supervisor is, due in part to a districting process that gives board incumbents substantial power to draw their own lines.

One reform attempt — not on the number of board members or the county’s executive leadership, but on redistricting — made it to the governor’s desk this year. SB 958 by Sen. Ricardo Lara, D-Bell Gardens, looks attractive on first blush in part because it borrows ideas from the California Citizens Redistricting Commission process that state voters adopted for state legislative races in 2008 (and expanded to congressional contests in 2010) to reduce the clout of the big political parties in divvying up seats.

Too many recent bills that target the L.A. County Board of Supervisors have missed the mark.

But the problem that proposed reform was designed to solve — the outsize power of partisan politics in shaping the districts that determine who gets to vote for whom — is negligible in county government. Like city councils, school boards, water district boards and other local bodies, county boards of supervisors are nonpartisan. Candidates may try to appeal to voters based on party affiliation, but they aren’t elected in party primaries or districts contoured to favor one party over another. The nature of nonpartisan offices is different from the Legislature or Congress. Candidates and voters rely less on their parties and focus more on nonpartisan issues.

Lara’s bill, which wouldn’t apply to any of the state’s other 58 boards of supervisors, would impose on L.A. County’s some of the partisan attributes of the Legislature. Redistricting commissioners — the people who ultimately would draw the lines — would have to reflect the party preferences of county voters. That means the commission would be overwhelmingly dominated by Democrats. To reflect the county’s population, it would make sense to create a commission whose members represent the county’s geographic, racial, social and economic makeup — or whatever other factors are deemed necessary to allow currently under-represented populations to finally elect supervisors of their choice. But a partisanship component is out of place on a nonpartisan board. This is not the reform we’re looking for. Gov. Jerry Brown should veto this bill.

Too many recent bills that target the L.A. County Board of Supervisors have missed the mark in other ways. One proposal would have allowed superior court judges to order an increase in the size of boards of supervisors and city councils in order to achieve better racial representation. Others were more specific, setting a mandatory seven-member or nine-member board instead of the current five.

Those ideas may be fine ways to achieve one important goal: to improve representation. But they fail utterly to address the fundamental structural problem of L.A. County’s board. There is limited value, to say the least, in creating a larger or more representative version of dysfunction.

Like states and nations, the county needs an elected executive alongside a representative body that adopts laws and holds that person accountable for his or her actions. It’s far too big and complex to be run by a five-person board, with no oversight. It needs checks and balances.

Although The Times editorial page has long called for such reforms, we’ve been unenthusiastic about measures that would enlarge or diversify the board if they leave the basic problems intact. The board is now in the midst of sweeping change, with two new members replacing multi-decade veterans two years ago, and two more soon to do the same. Supervisors have an opportunity to show they can get serious work done even with their current format. They have had some successes but have to produce better results, more quickly. Otherwise, some of those bills to shake up their current structure will look increasingly attractive.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.