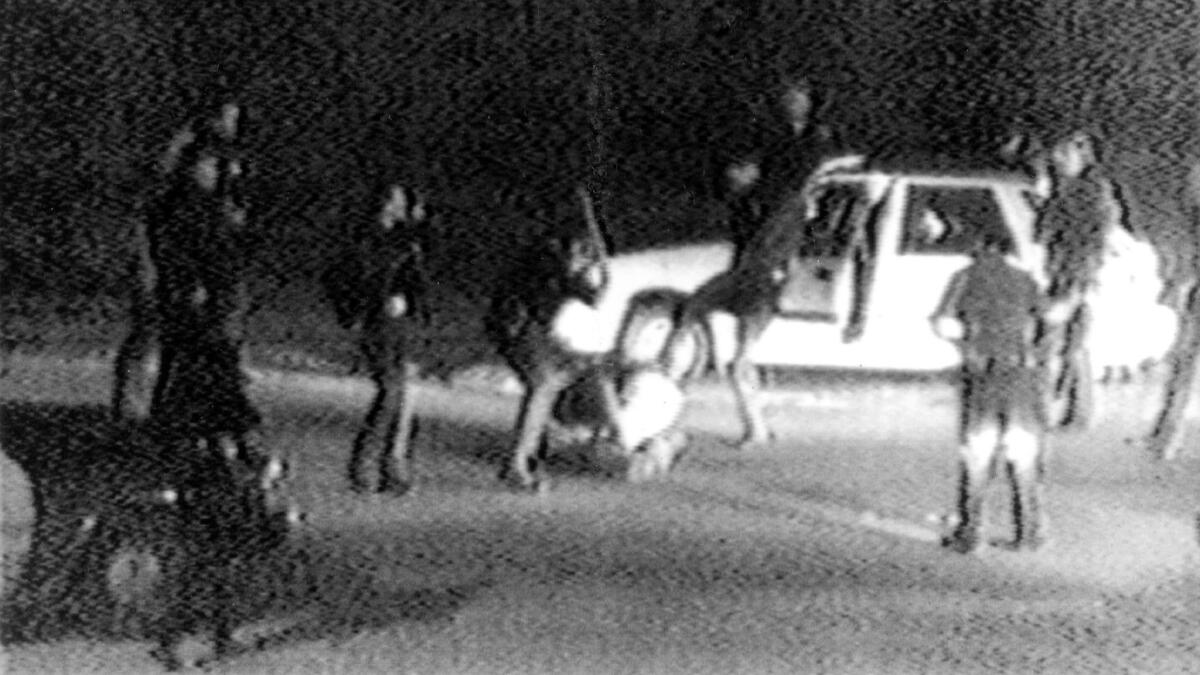

Editorial: The violence of 1992 and the acrimony of today were born with the videotaped police beating of Rodney King

Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley said what millions of people around the world were thinking on April 29, 1992, when a jury acquitted three LAPD officers of excessive force in the beating of Rodney King and failed to reach a verdict on the fourth.

“The jury’s verdict will never blind us to what we saw on that videotape,” Bradley said.

For the record:

8:57 a.m. Nov. 16, 2024An earlier version of this editorial said the beating of Rodney King occurred in Lakewood Terrace. The correct name is Lake View Terrace.

Presidential candidate Bill Clinton was similarly troubled.

“Like most of America I saw the tape of the beatings several times,” Clinton said, “and it certainly looks excessive to me so I don’t understand the verdict.”

Neither could the hundreds of Angelenos who angrily but peacefully protested, nor did many of the people who took part in six days of violence that left at least 55 dead, more than 2,000 injured, approximately $1 billion in damage and a psychic scar that still has not completely healed.

Video is evidence — one piece of it — and can never be a substitute for criminal trials or other open proceedings that weigh evidence and consider context.

As long as there have been police, officers have used force against suspected lawbreakers without the general public raising much of a fuss, except in those non-white communities that have been disproportionately affected by police force. But people cared about the King beating — they knew about the King beating — because they saw it. They saw the footage that was shot by George Holliday from his Lake View Terrace apartment balcony on March 3, 1991, and that was replayed on television countless times, just as today they see the controversial police shootings and beatings captured on surveillance cameras, private smartphones and officer body cameras. They came face to face with the violence inherent in police work — and the occasional abuse of official power.

But was it abuse? And was it merely occasional? Police and their supporters argue that officers necessarily do dangerous and violent work, and that a few seconds or minutes of video, taken out of context and viewed without sufficient expertise in police practices, can too readily mislead people into thinking they see police misconduct when in fact they merely see officers doing their very difficult jobs.

So police departments increasingly outfit their officers with body cameras that record encounters from start to finish — but in controversial cases they withhold public release of the images until the completion of lengthy investigations. Or they choose to release images immediately, but only when it tends to back their account, as in the case of the LAPD fatal shooting of 18-year-old Carnell Snell Jr. last year. Surveillance video showed that Snell was armed.

In Charlotte, N.C., last year, motorist Keith Lamont Scott was stopped and, after an exchange, shot to death by officer Brentley Vinson. Scott’s wife, Rakeyia Scott, was in the car, and she released smartphone video that arguably supported her claim that her husband was unarmed. The incident sparked a riot that did not, but easily could have, reached the level of violence seen in Los Angeles a quarter-century ago. Video later released by police supported their assertion that the driver did, indeed, have a gun.

Video is evidence — one piece of it — and can never be a substitute for criminal trials or other open proceedings that weigh evidence and consider context.

Still, what kind of counter-evidence and explanations can account for something like the fatal Chicago police shooting of Laquan McDonald in 2014? Video which was not released until more than a year after the deadly encounter certainly seems to support the contention that the shooting was unnecessary.

And what about the video that started it all — of the beating of King in 1992? As Bradley and Clinton said at the time, the video and the verdicts don’t match.

Yet there are police advocates who, to this day, argue that the beating was justified, and that when viewed in its entirety, Holliday’s tape offers sufficient justification for the police actions. A jury in Simi Valley agreed.

Today, the LAPD typically keeps officer bodycam video under wraps pending a full investigation. That’s a policy that should be revisited, this time with the benefit of public input. In cooperation with the Los Angeles Police Commission, the nonprofit Policing Project based at New York University School of Law is in the midst of a process of public outreach to help shape recommendations on the release of video and related issues (participate at https://policingproject.org/lapd-video-release/; Comments are being accepted through May 7).

Given that video of police incidents has become nearly universal since the Rodney King beating, a deeper conversation about the use and release of such images is warranted.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.