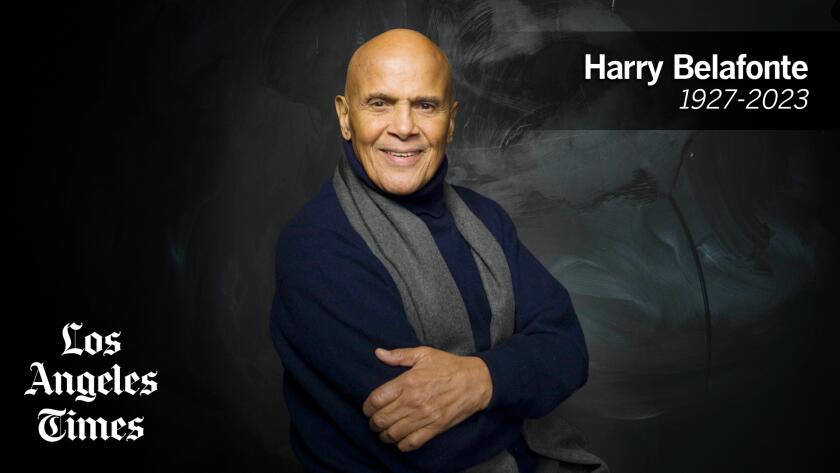

Harry Belafonte, singer, actor and civil rights activist, dies at 96

Singer, actor and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte dies at 96. He was the first Black man to win an Emmy and a Tony.

Segregation was rampant, doors were closed and, in 1950s America, the odds of a Black entertainer ascending to the Broadway stage, concert venues and screens large and small seemed impossibly long.

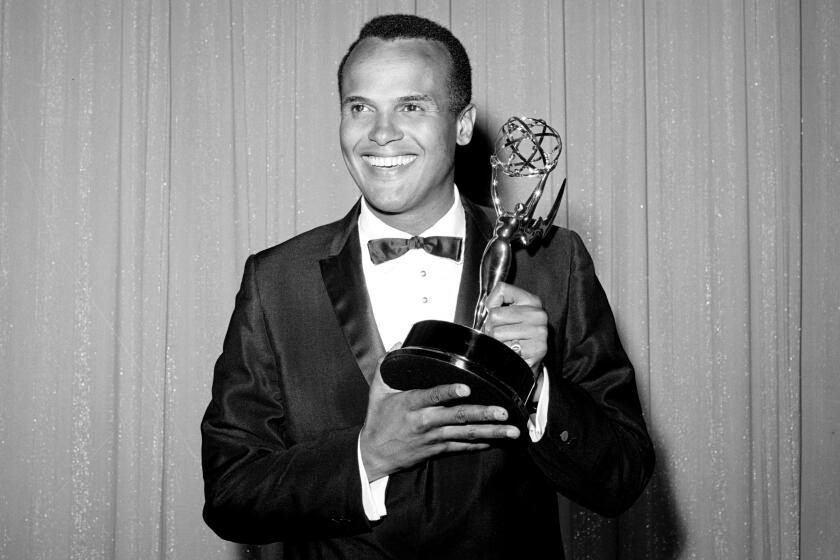

Yet with cool confidence, a magnetic charm and an armload of wistful Caribbean folk songs, Harry Belafonte beat the odds in a historic rise to stardom — the first Black man to win a Tony, the first Black man to win an Emmy, the first artist to record an album that sold 1 million copies.

Well aware of the battles still to be fought , Belafonte also became a civil rights activist, a confidant to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a friend of the marginalized and a globe-trotting humanitarian.

“I’ve got to be a part of whatever the rebellion is that tries to change all this,” he told the New York Times in 2001. “The anger is a necessary fuel. Rebellion is healthy.”

Long a symbol of what was right and decent in the world, Belafonte died Tuesday at his home in New York of congestive heart failure with his wife, Pamela, at his side, his longtime spokesman Ken Sunshine said. Belafonte was 96.

Belafonte, who fueled an international calypso craze in the 1950s with his addictive version of the “Banana Boat Song,” squeezed so much into his decades-long career that it was difficult to fathom it all.

Described in Look magazine in 1957 as the first Black matinee idol in entertainment history, the tall, trim and smoothly handsome singer amassed an impressive string of early accolades in an era when Black actors were mostly cast as maids, domestic helpers and laborers.

In 1954, he won a Tony Award for best featured actor in a musical for his performance in the Broadway revue “John Murray Anderson’s Almanac” and six years later won an Emmy for his performance in “The Revlon Revue: Tonight With Belafonte.”

His 1956 album “Calypso,” which included “Jamaica Farewell” and “Day-O,” his version of the “Banana Boat Song,” charted at No. 1 for a staggering 31 weeks.

This is one of our nine most surprising, historic and memorable moments from past Emmys.

With his signature stage attire of a partially opened tailored cotton shirt and tight black slacks, Belafonte captivated audiences. A 1959 Time magazine cover story called his act “a brilliantly planned and executed combination of artistry and showmanship.”

Belafonte’s emergence as a hugely popular entertainer with both Black and white audiences arrived during a post-World War II era when the civil rights movement was just coming into focus and attitudes were slowly shifting

“As far as Black entertainers were concerned, Belafonte in many ways seemed to be a startling new kind of figure,” said Donald Bogle, a culture critic and author of numerous books on Black Americans in film and television. “There hadn’t been somebody quite like him on the scene.”

Sidney Poitier, who made history as the first Black man to win an Oscar for lead actor and who starred in ‘Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,’ has died.

And television, which was becoming a potent cultural force in America at the time, helped make Belafonte and his music popular with a vast audience “because people could see him, and his look was very important,” said Bogle.

Through television, “you got a sense of his sex appeal,” said Bogle. “Women loved him and men felt comfortable with Belafonte as well.”

Belafonte was one of a number of popular Black entertainers and actors, including Sammy Davis Jr., Eartha Kitt, Dorothy Dandridge and Sidney Poitier, who emerged at the time.

Belafonte, whom singer and actress Diahann Carroll described to Time as “the most beautiful man I ever set eyes on,” was also visible on the big screen in a handful movies during the ’50s, a time when few Black performers were offered prominent film roles.

After making his movie debut in 1953 as a Southern school principal opposite Dandridge’s teacher in “Bright Road,” Belafonte starred with the actress in the hit 1954 musical “Carmen Jones.”

In 1957, Belafonte broke another color barrier — and stirred controversy — when he became the first Black American actor to play a romantic lead in a feature movie opposite a white leading lady (Joan Fontaine) in the Caribbean-set film “Island in the Sun.”

But, as Bogle observed, “the filmmakers would not allow Belafonte and Fontaine to kiss, nor was their relationship fully explored.”

In 1959, Belafonte starred in two films, “The World, the Flesh and the Devil” and “Odds Against Tomorrow.”

But, Bogle said, “Belafonte in movies was never what he was on television in terms of his impact, in part because of the compromises of the scripts and his own persona. He didn’t have that kind of magnetism on the big screen.”

Belafonte, whose later film credits included “Buck and the Preacher,” “Uptown Saturday Night” and “Kansas City,” established one of the first all-Black music publishing companies in the late ’50s.

It was part of Belafonte Enterprises, whose subsidiaries included a film production company called HarBel Productions. Other business units handled the singer’s concert tours and backed Broadway plays, including Lorraine Hansberry’s acclaimed “A Raisin in the Sun.”

A supporter of Sen. John F. Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign, Belafonte sang at Kennedy’s inaugural gala and was named “cultural advisor” to the then-newly created Peace Corps.

As his fame and fortune grew in the 1950s, the singer-actor devoted increasing amounts of his time and money to supporting the emerging civil rights movement.

Belafonte already was politically active when King called him in 1956 to ask the entertainer to meet with him at a Baptist church in Harlem while he was on a fundraising swing for the group running the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala.

The two men had a long, private meeting in a Sunday school classroom in the church basement.

“It was a life-changing moment,” Belafonte recalled in a 2007 interview with the Guardian. “From then on, I was in his service and in his world of planning, strategy and thinking. We became very close immediately.”

Belafonte’s friendship with King included holding a “secret” fundraiser in his Manhattan apartment to help raise bail money for King’s Birmingham campaign in 1963, knowing that some of the civil rights leader’s supporters would likely be arrested. Belafonte also rounded up a contingent of stars to appear onstage with King at the Lincoln Memorial during the historic March on Washington a few months later.

Belafonte, who helped launch one of the first voter registration drives in Mississippi and provided financing for the Freedom Riders, also served as a middle man between King and Atty. Gen. Robert F. Kennedy.

Decades later, Belafonte’s social activism took a high-profile twist.

Inspired by Irish singer-songwriter Bob Geldof’s Band Aid charity super-group, whose single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” raised money for famine relief in Ethiopia, Belafonte contacted talent manager Ken Kragen and proposed doing a similar project in the United States.

The result was the star-studded “We Are the World” recording that raised millions for famine relief in Africa in 1985.

Belafonte, who was appointed a UNICEF goodwill ambassador in 1987, was a 1989 recipient of a Kennedy Center Honor.

In a toast to Belafonte during the black-tie tribute, then-Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) said the entertainer “has given nobly and unselfishly to the cause of making our country a better place and our planet a better world. Many great artists have a conscience too, but none greater than his.

“He has two qualities that describe the brilliance of his life: courage and excellence,” Kennedy said.

Belafonte also was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994. And in 2000, the two-time Grammy winner received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

Throughout his long career, Belafonte continued to sing “Day-O,” which he once described as having become, “an established part of American folk culture.”

He wouldn’t think of doing a concert without performing it, he told The Times in 2000.

“I enjoy doing it very much,” he said, “and audiences enjoy it more than I do because they sing along with me — and they do it with gusto.”

Explaining the original “Banana Boat Song” in a 1993 interview with the New York Times, he said: “That song is a way of life. It’s a song about my father, my mother, my uncles, the men and women who toil in the banana fields, the cane fields of Jamaica. It’s a classic work song.”

He was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. in New York City on March 1, 1927. His mother was a domestic worker; his father, a violence-prone alcoholic at the time, was a cook who most often worked on United Fruit Co. boats between New York and Caribbean and South American ports.

“I was born into poverty, grew up in poverty, and for a long time, poverty was all I thought I’d know,” Belafonte wrote in his 2011 memoir “Harry Belafonte: My Song.”

He made a number of visits to Jamaica when he was young. And in 1936, when he was 9, his mother took him and his 5-year-old brother Dennis to Jamaica to live full time to get away from what he later said were the dangers and temptations of living in Harlem.

When their mother was unable to find a job in Jamaica, she returned to New York and left her two sons behind to attend school. Belafonte’s parents were legally separated by 1940 and his mother brought him and his brother back to New York to live with her.

Belafonte, who later discovered he was dyslexic, dropped out of school midway through the ninth grade and worked a series of odd jobs before enlisting in the Navy shortly after turning 17 in 1944. He was stationed at Port Chicago outside San Francisco, where he loaded military ships bound for the Pacific theater in the final months of World War II.

Returning to Harlem after his discharge in December 1945, he got a job working as a janitor’s assistant in an apartment building.

That January, he hung Venetian blinds for a tenant, an actress, who as a tip gave him two tickets to a play at the American Negro Theatre in Harlem.

The play, about Black servicemen returning home to Harlem, was the first he’d ever seen, and it changed his life.

“That play didn’t just speak to me. It mesmerized me. This was a whole new world — an exhilarating world,” he wrote on his memoir.

He had no intention of becoming an actor at the time, but just to get close to this wonderful new world, he volunteered to be a stagehand at the theater.

A tribute to Sidney Poitier, with love.

He soon was asked to read for a small role in a comedy. That led to a larger role in another play. By July 1946, Belafonte was playing a leading role in the American Negro Theatre’s production of “Juno and the Paycock.”

Belafonte, who became close friends with another fledgling young actor at the theater, Sidney Poitier, began attending the Dramatic Workshop of the New School for Social Research on the GI Bill.

A break in landing a role in an off-Broadway production of “Sojourner Truth” in 1948, however, did not immediately lead to more acting jobs for the 21-year-old Belafonte.

Newly married to his first wife Marguerite, he began working full time pushing clothes racks in the Garment District.

Then an unexpected break came: The manager of the Royal Roost, a top New York City jazz club, who had heard Belafonte sing in a play, offered him a job singing during intermissions.

Before long, Belafonte was packing the club, and he went from making $70 a week to $200 a week.

“It was breathtaking,” Belafonte recalled. “I went from being a nobody who didn’t think he could sing to walking on stage at Carnegie Hall, one night that spring, to accept a plaque from the Pittsburgh Courier, an African American newspaper, as the most promising new singer in the country.”

Twice divorced, Belafonte had four children, Adrienne and Shari with his first wife, and David and Gina with his second wife, Julie. He is also survived by his wife, Pamela Frank, and eight grandchildren.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.