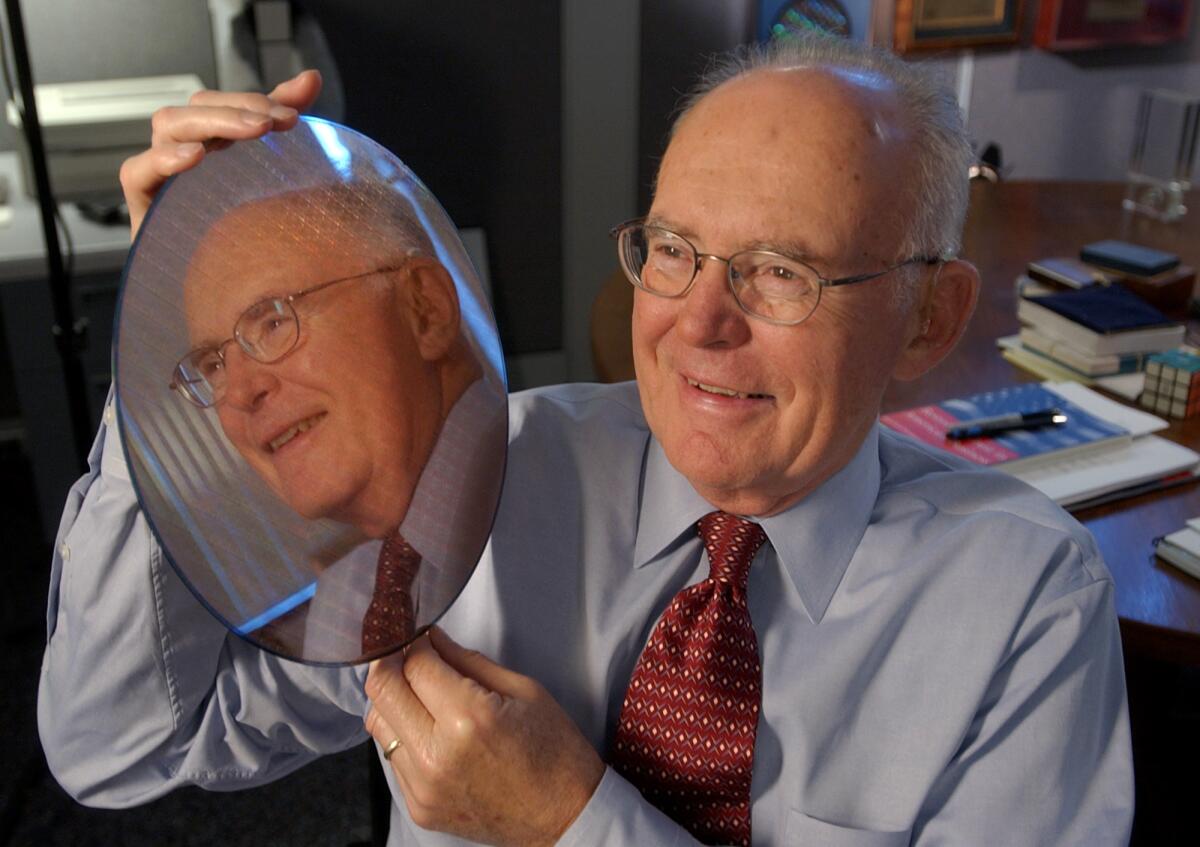

Gordon E. Moore, Intel founder and creator of Moore’s Law, dies at 94

Gordon E. Moore, co-founder of Intel Corp. and creator of Moore’s Law — the mantra of boundless technological development that came to define the digital age — has died at age 94.

Moore died Friday at his home in Hawaii, according to the company and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

From humble roots as the son of the sheriff of Pescadero, Calif., Moore went on to create Intel, one of the greatest technological powerhouses of the 20th century.

Moore, who was trained as a chemist, was among the earliest pioneers in the creation of the integrated circuit, chips of silicon that came to form the backbone of modern technology.

He was among the small group of engineers and scientists, including Nobelist William Shockley, one of the co-inventors of the transistor, and Robert Noyce, the co-inventor of the integrated circuit, who put the silicon in Silicon Valley.

But what distinguished Moore beyond many of his legendary peers was that he also had a blend of skills that extended far beyond the merely technical.

As the chairman of Intel, Moore guided the company with a homespun demeanor and the spirit of a Las Vegas gambler.

Taking the risky path was something that came naturally to him, although he always maintained that his risks were clear choices that had to be taken.

“This is a fast-moving business,” he once said in an interview. “Unless you’re willing to take technical and financial risks, you’re doomed. Things change so fast, if you don’t, you die.”

Moore described himself as an “accidental entrepreneur,” although the success of Intel — and Moore’s status as one of the richest men in the country because of his Intel holdings — belied his humble assessment.

Although Moore’s co-founding of the microprocessor giant in 1968 assured his place in the history of modern technology, he may be best-known for what became known as Moore’s Law.

In 1965, Moore made a simple observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit appeared to be doubling every year.

The integrated circuit had been invented only seven years earlier, and the most that anyone had been able to etch onto the thin chips of silicon that would power the growth of the electronics industry was about 50 transistors.

Looking at a graph of chip development, Moore extended the line forward 10 years and predicted that by 1975 there would be 65,000 transistors on a single silicon chip. It seemed an outlandishly large number at the time, but Moore was right on target.

Moore amended his prediction several times during his life, eventually settling on the prediction that the number of transistors would double every 18 to 24 months instead of every year.

But although the exact equation of Moore’s Law was changed, its spirit of rapid technological advancement remained constant. It became the credo of the electronic world and a slogan of the digerati eagerly awaiting the next great thing.

“Integrated circuits will lead to such wonders as home computers — or at least terminals connected to a central computer, automatic controls for automobiles, and personal portable communications equipment,” Moore wrote in 1965.

The descendants of the first crude chips that Moore designed went on to power personal computers, automobiles, mobile phones and even watches.

“It’s kind of funny that Moore’s Law is what I’m best-known for,” he said in a 1997 interview with Business Week. “It was just a relatively simple observation.”

The accuracy of Moore’s Law became a cornerstone of business planning in the electronics industry.

Gordon Earle Moore hardly fit the image of a prophet of the digital age. He was down-home and practical, an unpretentious, slightly balding scientist who maintained a bit of his small-town roots in the midst of the heady pace of Silicon Valley.

Moore was born in San Francisco on Jan. 3, 1929, to Walter and Florence Moore. The family eventually settled in Pescadero, about 30 miles south, where his father was the chief deputy sheriff for the area.

Moore seemed headed for an academic career after graduating from UC Berkeley with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1950 and a doctorate in chemistry and physics from Caltech in 1954.

After a brief stint at the Applied Physics Lab at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, he went to work in 1956 for Shockley, who had set up his own company, Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, to further develop the transistor. Shockley was a heavy-handed, temperamental and capricious manager. After working for just a year, Moore and most of Shockley’s top scientists rebelled.

The “traitorous eight,” as Shockley called them, broke away and started Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957. The creation of Fairchild was one of the crucial turning points in electronics history, allowing Moore and others to pursue research that helped their partner, Robert Noyce, to devise a commercially viable process to miniaturize whole circuits on a silicon chip — the integrated circuit.

Moore and Noyce left Fairchild in 1966 and two years later formed their own company to exploit the development of the integrated circuit. They named their company Integrated Electronics but later shortened it to Intel.

With the help of Arthur Rock, the first of Silicon Valley’s legions of venture capitalists, Noyce and Moore easily raised $2.3 million and began work. Noyce served as chief executive officer of the new company with Rock as chairman and Moore as executive vice president.

Intel began by making memory chips and rocketed to profitability by adopting a corporate strategy of innovating at a breakneck pace so that it could charge a premium for its products.

Moore took over as chief executive of Intel in 1975, just a few years before his company began being battered by the flood of cheap memory chips from Japanese manufacturers that turned Intel’s main product into a commodity.

Intel began losing money and laying off workers. By the mid-1980s, Intel had begun to lag in the very industry it had created.

By 1985, even Moore began to sound grim. The downturn, Moore told shareholders at the time, was “possibly the greatest in the history of the semiconductor industry.”

“We are flushing out the excesses of a badly overheated electronics industry,” he said. “What happened? Dame Fortune frowned. Intel must be well-positioned and ready when Dame Fortune smiles again.”

In 1984 and 1985, Intel still spent more than $1 billion on chip-manufacturing equipment and facilities. It was all part of Moore’s belief that staying on the cutting edge was the key to success and the company would eventually come roaring back.

Moore and the hard-charging president of the company, Andrew S. Grove, began to refocus Intel away from cheap memory chips to high-margin microprocessors — the brains of the computer.

In 1987, Moore relinquished the chief executive position to Grove, although he remained active in guiding the company as chairman.

Moore also busied himself as a member of the Caltech board of trustees and as a patriarch of the electronics industry.

In 1950, Moore married Betty Irene Whitaker, who survives him. Moore is also survived by sons Kenneth and Steven and four grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.